Fuse Book Interview: George Kimball Takes The Library of America to The Fights

“Jack London was rather like Norman Mailer in that he thought of himself, and tried to write like, a boxer who happened to write. They were both often full of shit, but that’s the perspective they tried to convey. “

By Bill Marx.

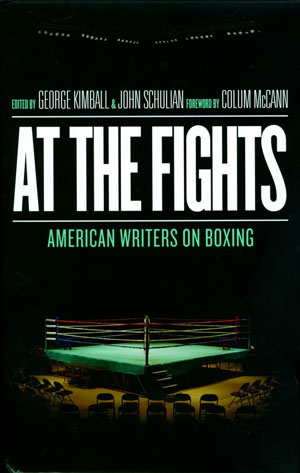

“‘Writin’ is fightin’,” claims African-American author Ishmael Reed. Sentences need not always be so belligerent, but fighting has inspired American writers to craft powerfully muscular prose for over a century. Wordsmiths from the literary to the journalistic have been galvanized by the elemental physical experience, exotic cultural geography, and electric social resonances of the sport. The Library of American asked two expert writers on boxing, John Schulian and George Kimball, to gather together the best examples of authors chronicling the world of fisticuffs in the anthology At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing.

A long time sports writer for the Boston Herald, Kimball has written Four Kings: Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, Duran, and the Last Great Era of Boxing as well as Manly Art: They can run–but they can’t hide. He edited an earlier anthology on the sport with John Schulian, The Fighter Still Remains: A Celebration of Boxing in Poetry and Song from Ali to Zevon. He and Schulian are featured in an extensive interview on the Library of America website about At the Fights, but I wanted to throw Kimball a few more questions.

Arts Fuse: In his Foreword to At the Fights, Colum (Let the Great World Spin) McCann asserts that “writers love boxing.” More than baseball? And does that affection continue?

George Kimball: I don’t know that more writers love boxing than baseball, but I think boxing over the years has produced more great writing than even baseball has. We’re clearly in a lull right now. Most of the good boxing books that have been turned out in recent years have been those that looked back at earlier eras.

I was the one deputized by Max Rudin to ask McCann about writing the Foreword. I remembered having years earlier read one of his short stories called “Step We Gaily On We Go,” in which the protagonist is an ex-boxer, a character so well-rendered that I assumed that its author had to be either a practicing pugilist himself or a dyed-in-the-wool, hard-core boxing fan, though it turned out Colum was really neither.

After an event at Symphony Space–this would have been almost a year ago, not terribly long after he’d won the National Book Award–we’d gone with a few friends to an Upper West Side pub to discuss the matter, and Colum’s initial reaction was that he feared he didn’t really have enough of a boxing background to do the subject justice. “But you understand great writing,” I told him. “That’s what this is all about. The subject just happens to be boxing.” He said he’d think it over.

As the evening wore on and the pints kept coming, the very metaphors that wound up in the Foreword periodically emerged across the table like bolts out of the blue: the ring, the punch, the bell, the deadline. By the end of the night he still hadn’t committed, but by then not only did I know he was he going to do the foreword, but that he had half of it written in his mind already.

AF: The first author in the anthology is Jack London. What was American writing on boxing like before the turn-of-the-century?

Kimball: Very little of it appeared in mainstream newspapers until 1892. The adoption of the Queensberry rules made boxing a more socially acceptable topic for mainstream coverage, and the Sullivan-Corbett fight that year brought widespread coverage. Up until then boxing was covered, when it was covered at all, in places like the Police Gazette. Not only was it considered unsavory, but in many jurisdictions it was illegal.

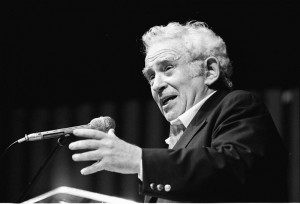

London was rather like Norman Mailer in that he thought of himself, and tried to write like, a boxer who happened to write. They were both often full of shit, but that’s the perspective they tried to convey.

London’s story on Johnson-Jeffries, which opens the book, is a true historical marker. There was more copy transmitted from that fight than from any single event in the world until Lindbergh landed in Paris 17 years later, and London, of course, had done more than anyone to bring Jeffries out of retirement as the “Great White Hope.” He’d been agitating since he watched Johnson beat Tommy Burns for the title in Australia a few years earlier, but he was at that fight almost by accident. He and his wife were on a round-the-world sailing trip (aboard the Snark) when he fell ill in the South Seas. He thought he’d contracted leprosy (it turned out to be psoriasis, so they left the sailboat at Guadalcanal and took a ship to Sydney to seek treatment.

AF: How does the best American writing about boxing differ from the approaches of European authors?

Kimball: The pioneer of all boxing writers was of course an English writer, Pierce Egan, whom Liebling often cited as his muse. (I credit Egan with apologies to William Hazlitt, who essentially covered one fight, though he did it very well.) George Bernard Shaw was writing about boxing when few “serious” European writers did, and of course before him Byron boxed. Today’s British newspapers cover boxing more diligently than do their American counterparts, and the top British sportswriters like Hugh McIlvanney and James Lawton do it splendidly. I’d say the major difference in approach today is that for the most part British writers tend to be less cynical than ours.

I haven’t read as much French and German coverage, but their sportswriters tend toward boosterism, particularly of their own fighters, and this isn’t necessarily a desirable trend. A boxing writer isn’t supposed to be a fan, but sitting at ringside at a fight in Europe (or over here when one of theirs is involved), these guys are often unabashed rooters.

AF: One of the stylistic battles in the book is between writers who want to capture the visceral excitement of the bout or the seedy charm of the boxing world and those who see fighting as a platform for an analysis of the sport and social attitudes. Would you agree?

Kimball: I don’t know that “battle” is the appropriate term, and in fact writers who are attracted by the seamier underpinnings of the sport can still be dazzled by a virtuosic performance in the ring. I don’t think many writers have consciously set out to explore social attitudes and trends by using boxing as a metaphor, though it sometimes works out that way.

AF: A. J. Liebling is generally considered by critics to be the best American writer on boxing. If he is at the top, who are the runners-up and why?

Kimball: Not Mailer and not Hemingway, although they’d probably think they were. Just off the top of my head, the worthy contenders would include Budd Schulberg and W. C. Heinz for certain, but also Mark Kram and Pat Putnam from SI, [and] Ralph Wiley, all of whom really understood the sport in addition to being wonderful writers.

AF: There are some really rare finds here–for example, pieces by Richard Wright and Sherwood Anderson on Joe Louis. How difficult was the research for the anthology? What are some of your favorite pieces?

Kimball: I wouldn’t describe the research as “difficult,” because it was such a pleasure. We probably read a half-dozen really good pieces for every one that wound up in the anthology. We read some pretty awful ones, too, mostly when we’d been touted by someone who should have known better.

The Wright and Anderson pieces on Joe Louis weren’t that hard to find, but there were some we found almost by blind luck. We’d planned on using another Larry Merchant column, but then the composer David Amram happened to mention to me that Larry had written a column about this crazy, 550-mile round trip the two of them had made between a premiere of David’s opera and a fight in Philadelphia back in the sixties. I knew the date of the Griffith-Gypsy Joe Harris fight, so starting from there and moving ahead, I was able to find it on microfilm at the NY public library.

On another occasion I was actually looking for something else in the NYPL microfilm room when I stumbled across Frank Graham’s column on Marciano and Charles. John and I agreed that, especially as an example of pure deadline writing, it worked better than another Graham piece we’d earlier earmarked for the book.

I’ve been asked that question by several people over the past couple of months and usually manage to duck it by saying “Which of your children is your favorite?” But I will say that John Lardner’s masterpiece on Stanley Ketchel, “Down Great Purple Valleys,” is sort of the cornerstone of the whole book. With all the other changes we went through in compiling At the Fights, that was the one indispensable story, if only because it so exemplified what we wanted to do with the rest of the book–and that was setting the bar pretty high.

AF: Understandably, boxing brings out the macho posturing in writers, Norman Mailer the poster boy for this kind of swagger. Has this “winner take all” mentality been good for writing about the sport?

Kimball: No. For all his bluster, Norman was a terrific writer, even when he didn’t know what he was talking about, but most of the best writing about boxing has been tempered by a certain humility.

AF: Do the female authors in the anthology, such as Joyce Carol Oates and Katherine Dunn, bring a fresh perspective to boxing?

Kimball: Obviously they bring a different perspective. The two pieces we used in the anthology–Oates on Tyson and rape and Dunn on Lucia Rijker–are as effective as they are precisely because they were written by women. I can’t imagine a male writer, just for instance, being anything but self-conscious trying to explain coordinating the use of birth-control pills to regulate menstrual cycles around the scheduled date of a fight. In fact, I can’t imagine Lucia even telling a man about it.

AF: Many of the pieces are by writers who worked for big city newspapers. Does the waning of print journalism spell the end of a tradition of writing about boxing? Or are there places on the internet that feature first rate prose about boxing?

Kimball: There’s some pretty good writing on the internet, though you have to negotiate a minefield of pretty wretched writing unless you know where to look. The internet has actually become the last refuge of some of the members of my generation. But the “boxing writer” who exclusively covers boxing no longer exists at newspapers, and as you suggest, newspapers themselves increasingly cease to exist. But boxing has always been a cyclical sport, and right now it’s in a down-cycle; I think that as more compelling fights and compelling fighters come along, the best writers will find their ways there again.

A must read book if you’re a boxing fan and for everyone else for that matter. The sport of boxing has been lucky to have George Kimball, whom my father (Budd) would rank all the way at the top.