Film Review: “Lynch/Oz” — The Man Behind the Curtain

By Nicole Veneto

Without The Wizard of Oz, it’s entirely possible that the David Lynch we know and love wouldn’t exist.

The opening montage that begins Lynch/Oz. Photo: Janus Films

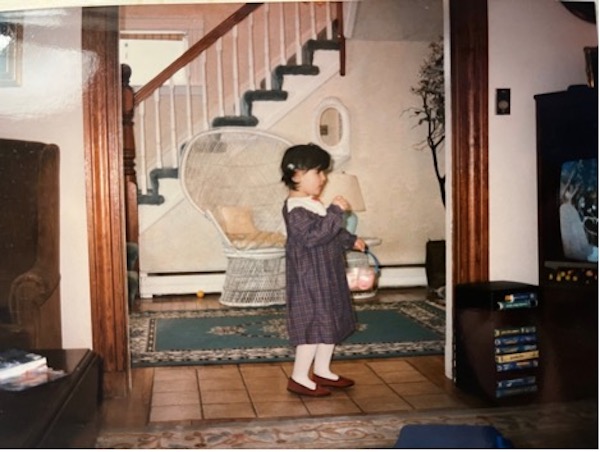

My film journey begins at about the age of three with my father’s second-generation VHS copy of The Wizard of Oz. Some of my earliest and most vivid memories are of making my dad pause the tape just before Dorothy steps out into the luscious technicolor of Oz to help me put on a little gingham dress and braid my hair (no small feat for his thick drummer fingers, but he tried his best) so I could skip along the yellow brick road. While I was helping my mom clean out my childhood home to put on the market a few years ago, I found pictures of myself in full Dorothy get-up standing in front of our old Zenith television, completely and utterly transfixed. In the years that followed throughout my childhood, I maintained this fascination with Oz through Halloween costumes and deep dives on the internet into the ownership history of the Ruby Slippers. Oz was more or less my gateway drug into the celluloid world, the significance of which cannot be stressed enough. It’s a film I’ll forever associate with my parents, who first experienced Oz when it would ceremoniously air once a year on their black-and-white television sets as children.

And then, when I transitioned from adolescence to young adulthood, I “discovered” David Lynch, and the trajectory of my filmic life changed forever once more. Hard to say what my first Lynch experience was — it might have been watching Eraserhead On Demand with my mom, skipping homework to watch Mulholland Drive and Wild at Heart, or seeing parts of The Elephant Man (arguably Lynch’s most accessible film next to the aptly titled The Straight Story) on AMC. But it wasn’t until I finally watched Twin Peaks my freshman year of college that I became a serious Lynch acolyte. Like Oz, Twin Peaks became a deeply ingrained obsession of mine. There were staggering parallels to my upbringing on Oz: Halloween costumes (I was Audrey Horne two years in a row), numerous internet rabbit holes, and merchandise. The intertextual parallels between Oz and Lynch’s entire filmography, however, are self-evident to anyone with even a passing familiarity with Oz. In fact, without Oz, it’s entirely possible that the David Lynch we know and love wouldn’t exist.

Me, at about three years old, bewitched by The Wizard of Oz in my little Dorothy outfit. Photo: my dad

Documentarian Alexandre O. Phillippe’s latest film, Lynch/Oz, couldn’t have been better tailored to my sensibilities if it tried. Divided into six chapters of mini-film essays narrated by critic Amy Nicholson, fellow documentarian Rodney Ascher (A Glitch in the Matrix and Room 237), and filmmakers John Waters, Karyn Kusama, Justin Benson and Alan Moorhead, and David Lowery, Lynch/Oz explores the through lines between The Wizard of Oz and Lynch’s filmography. Advertised as “cinematic catnip” for film nerds, the doc amounts to a series of better-than-average produced YouTube film essays spliced together to feature length. There was no direct involvement with Lynch. Those who are expecting something as unconventional in sensibility as Lynch himself will be disappointed. I would respond that several of those documentaries already exist: David Lynch: The Art Life, Eraserhead Stories, and blackANDwhite’s Lynch (one) and Lynch 2. But all of those docs place the locus of interpretation on Lynch himself. Lynch/Oz is something different: it is an attempt by Lynch acolytes to analyze his films through the Rosetta Stone that is The Wizard of Oz, an interpretive lens that ends up paying dividends, though no firm answers are offered. However, it will certainly expand your understanding of Lynch’s modus operandi, as Gordon Cole would say.

Much of Lynch/Oz points out the fairly obvious connective tissue between Lynch’s filmography and Oz. The argument is that much of his directorial style borrows visual and referential signifiers from Oz, the latter having established a “shared language” with American audiences: billowing curtains, red shoes, ominous whooshing noises, doppelgängers, and little dancing men. This association is at its most pronounced in Wild at Heart, where Mairetta Fortune’s (Diane Ladd) villainous attempts to break up her daughter Lula’s (Ladd’s real-life daughter and frequent Lynch collaborator Laura Dern) relationship with Sailor (Nicolas Cage) literally and metaphorically transform her into the Wicked Witch. A cursory look through Lynch’s filmography will reveal even more Oz Easter eggs, from character names (Dorothy Vallens in Blue Velvet and Major Garland Briggs in Twin Peaks) to the very invocation of Oz’s tragic star, Judy, throughout Twin Peaks: The Return. (Why don’t we talk about Judy? Maybe it’s because, like Laura Palmer, the tragedy of Judy’s life is too painful to put into words.)

Promotional still for Lynch/Oz. Photo: Janus Films

The crown jewel of Lynch/Oz is its centerpiece, “Chapter 3: Kindred,” an informative presentation by John Waters that focuses on his own relationship with Oz and decades-long association with Lynch. Waters and Lynch are forever intertwined in the history of underground ’70s cinema: Eraserhead and Pink Flamingos were frequently the double bill on the midnight movie circuit. Waters was also one of Eraserhead’s earliest champions, allegedly devoting almost an entire Q&A after a screening of Flamingos to telling people to see Lynch’s stunning feature debut. As the subtitle for this section of the film implies, Waters sees Lynch as a kindred spirit, despite the differences in their respective approaches as filmmakers. The two have crossed paths numerous times, most famously enshrined in a 1977 photo of them shaking hands in front of a Big Boy burger restaurant (where, according to Waters, Lynch used to eat lunch every day for several years). Beyond their shared use of Oz signifiers, Waters notes the similarity in their onscreen moral compasses as another substantial link between their filmographies: good and evil are clearly demarcated, a thematic obsession that colors every single one of Lynch’s major movies. The dichotomy between good and evil, light and dark in Lynch’s work might be the definitive characteristic of the Lynchian style. In Waters’s films, the antagonists are often nosy busybodies who want to control how other people live their (disgusting, filthy, and gloriously queer) lives, who’d do well to abide by Gordon Cole’s advice to “Fix your hearts or die.”

Second only to Waters’s contribution is that of Karyn Kusama, director of the late-aughts cult hit Jennifer’s Body and a seemingly odd choice for a documentary about Lynch’s relationship to Oz. Narrating the section “Chapter 4: Multitudes,” Kusama mainly focuses on the numerous parallels between Oz and Mulholland Drive, the starting point being a Q&A she attended after the film’s premiere at the New York Film Festival. Lynch’s typically reticent approach to talking about the meaning of his films was momentarily broken when an audience member asked him to talk a little bit about Mulholland Drive’s relationship to The Wizard of Oz. Kusama recalls that Lynch got quiet for a second and then said, with the sort of wonder a child would, “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about The Wizard of Oz.“ That response radically transformed Kusama’s perspective on Lynch’s career, especially when it came to interpreting the puzzle box that is Mulholland Drive, such as the blue key Naomi Watts’s Betty finds in her purse in the Silencio club. Of course, the narrative archetype of journeying between two worlds — which represent two different extremes — wasn’t a concept Oz invented. But Oz has become the great American fairy tale, so it implanted the notion in the collective unconscious.

As in Oz, when it comes to the work of Lynch, nothing is ever as it seems. It’s this very ambiguity of meaning that make his movies so ripe for interpretation, whether it’s from a metatextual position or in intertextual readings with Hollywood’s Golden Age. If there is one certainty about Lynch’s films, though, it is that they are in constant dialogue with The Wizard of Oz and its massive cultural footprint. Lynch/Oz doesn’t deliver a final word on what Lynch’s work is about, but by applying the emerald-tinted lens of Oz, Phillippe makes what might be the strongest case for his films being strange and wonderful trips over the rainbow.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and her podcast on Twitter @MarvelousDeath.