Book Review: “Second Star and other reasons for lingering” — Making the Case for Concentration

By Thomas Filbin

The point of the revelatory exercises in Second Star is to mentally invigorate, to sharpen how we look at the things in plain sight that we take for granted.

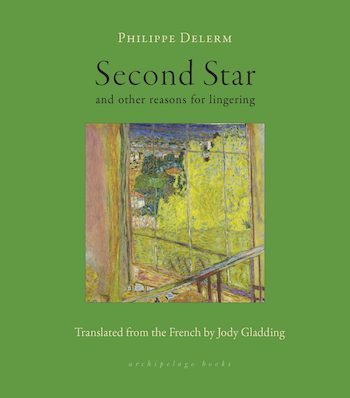

Second Star and other reasons for lingering by Philippe Delerm. Translated from French by Jody Gladding. Archipelago Books, 154 pp., $18.

Philippe Delerm has written a short but poignant book that could be called a work of fiction, a prose poem, or a gathering of short essays. I prefer to think of the volume as a collection of meditations, reminiscent of Thomas à Kempis’s approach in The Imitation of Christ. It is not a religious tract, but its assemblage of short two-page essays invites readers to pause and reflect, especially on things we pass or experience every day but file in the back of our brains as disposable backdrops to what we consider to be life’s main attractions.

Philippe Delerm has written a short but poignant book that could be called a work of fiction, a prose poem, or a gathering of short essays. I prefer to think of the volume as a collection of meditations, reminiscent of Thomas à Kempis’s approach in The Imitation of Christ. It is not a religious tract, but its assemblage of short two-page essays invites readers to pause and reflect, especially on things we pass or experience every day but file in the back of our brains as disposable backdrops to what we consider to be life’s main attractions.

The 60 entries are not arranged or linked in any particular order or connection. Rather, they are strewn about randomly, like flowers in a field. Delerm takes up various topics, such as “The Embarrassment of Vaping,” “Dancing Without Knowing How to Dance,” “The Sounds of Venice,” and “The Troubled Waters of the Mojito,” and treats them with a compelling mix of wisdom and whimsy. At their best, his essays dovetail acute observation with a sense of humor that could be called both sophisticated and childlike. To truly see what is in front of us is a habit/ability that seems to be slipping away as humanity becomes increasingly Google-dependent. We click our way through our interests — we stare but do not observe. Recognition without a call for concentration.

In “A Hip Move and Memory,” the narrator describes awakening in the morning and becoming conscious of the cat lying next to him. He takes care not to move abruptly and disturb the animal. The cat is indifferent to the man’s consideration; he is only waiting for his morning milk. This gesture becomes a morning routine, unconsciously linked with first light. Like all habits, it survives beyond its usefulness: the narrator tells us it continued weeks after the aged cat had died. He says, “I’ve kept him here in my body. I haven’t forgotten.” But, over time, the reflex response passes and our narrator makes a sad recognition: “None of this is under your control. You forgot the cat the moment you thought you would always remember him.”

“A Summer Evening” describes a gathering of friends for a meal in the garden. “We set out candles almost everywhere, on the window sills, in the branches of the old quince and apple trees. At the stroke of ten we pull on sweaters, but it’s not cold and everyone wants to stay longer. We’ve all had too much to drink, but our friends live five hundred meters away, they walked over. Friends for almost our whole lives, completely at ease.” The mood is of self-justifying indolence, of people not needing to be anything other than who they are. The fleeting fragility of a summer night needs no further justification than the pleasure it gives. The being-in-the-moment is its only purpose — no need to pretend it is some eternal or immortal event. As we age, we realize that “here and now” is not a bad thing.

Author Philippe Delerm. Photo:WikiCommon

“The Time of the Pocket Watch” recalls an era when “men of a certain age, often stout, bourgeois senators of the Third Republic” took a gold or silver watch from the small pocket at the front of the waist and it was “… proudly wielded, unhurriedly consulted, held at arm’s length from the body.” This picture is compared to today’s quick look at the wrist watch or the cell phone before dashing off. The White Rabbit’s cry of “I’m, late, I’m late, for a very important date; no time to say hello/good-bye — I’m late!” suggests the panic when telling time on the run. The pocket watch has become a souvenir of standing still and possessing time.

“Vendor for a Day” considers large antique and second-hand fairs. Delerm uses these markets to speculate on how objects can unite people who have similar affections. Love of material culture seems to inevitably create community. People at a fair often talk shop, examine objects, and make comparisons. A man who loves old clocks will bond with someone else who has such a passion. Soon strangers — now convivial — will agree to have a glass of wine as closing hour approaches.

Lost love, childhood, old age cruelly stripped of memory by Alzheimer’s, work, play, selfies, and whiskey all find their way into these brusque slices of contemplation, their revelations simple yet also complex. Delerm finds resonant meanings in everyday objects, moments, and coincidences, burrowing into surprisingly emotional depths as he probes attachment and loss. None of his reflections will likely make a reader change his philosophical stance, but that is not his purpose. The point of the exercises in Second Star is to mentally invigorate, to sharpen how we look at the things in plain sight that we take for granted. To discover the significance of the world outside of what our omnivorous computer screens dictate.

Thomas Filbin is a book critic whose work has appeared in Tthe New York Times Book Review, Boston Sunday Globe, and Hudson Review.