Music Feature: “Shared Spaces” — Breaking the Silence

By Helen Epstein

So much of David Sakura’s narrative in Shared Spaces reminded me of the stories of other traumatized groups.

Shared Spaces: An evening of music and spoken word reflecting on the Japanese-American experience. Presented by the Sheffield Chamber Players at Cambridge’s Multicultural Arts Center on April 30.

Shared Spaces: l-r: Alexander Vavilov, Sheffield violist; Megumi Stohs Lewis, Sheffield violinist; David Sakura; Kenji Bunch, composer; Leo Eguchi, Sheffield cellist; Sasha Callahan, Sheffield violinist. Photo: Sheffield Chamber Players

I rarely get to the Cambridge Multicultural Arts Center, but had the good luck to catch an unusual performance of words and music, perfectly suited to that intimate and community-minded venue. The musicians were the Sheffield Chamber Players, a chamber music group based in Jamaica Plain that performs in a wide variety of public and private venues. Its members are all active champions of new music and play in many other chamber groups, orchestras, and festivals across the country, as well as teach. This program featured the premiere of a commissioned work, “String Quartet No. 5, Songs for a Shared Space,” by Oregon-based violist/composer Kenji Bunch, along with some of his shorter compositions. The pieces of music were interwoven with a text by David Sakura, an 87-year-old American internment camp survivor, who served as narrator.

The idea for a reading with music grew out of two friendships. Sheffield’s first violinist Sasha Callahan and composer Kenji Bunch played in the Portland, Oregon, youth orchestra as kids. Much later, Callahan, her cellist husband Leo Eguchi, and David Sakura met during summers at the New Hampshire Music Festival. The four and the other two members of the quartet, Megumi Stohs Lewis and Ukrainian-born Alexander Vavilov, comprised a flawless ensemble.

I came to the concert wondering how the intergenerational transmission of culture as well as trauma could be translated into musical performance. I had seen the powerful International Center for Photography’s 2018 exhibit Then They Came For Me and Jeanne Sakata’s Hold These Truths at the Barrington Stage in 2019.

Shared Spaces has no set that separates performers and listeners. The performance begins with composer and musicians sitting among the audience and, one by one, walking into the center of the stage space to join a narrator standing beside a TV console. Bunch (born in 1973), whose mother survived World War II in Japan, wrote all the program’s music — “Ghost Mine for solo cello”; “Minidoka for solo viola”; and String Quartet No. 5 — in response to visiting the site of the Minidoka internment camp and to his family history. I did not hear his music as explicitly programmatic, but as evocative of many different musical styles and folk traditions that I find hard to describe. Below is Bunch’s own 2017 performance of “Minidoka for solo viola”.

David Sakura was six years old when his family was deported from their home in Eatonville, Washington, to a nearby temporary detention center named “Camp Harmony.” He was then transferred to Minidoka in a desolate part of southern Idaho and had turned eight when his family was finally released from imprisonment.

His concise, effective script consists of “voices,” compiled by Sakura from newspaper articles, letters, and conversations with members of his family. His narration is accompanied by photographs, documents, and film footage shown on the small screen.

The first voice is that of Toyozo Sakura, who was born in Japan but dreamed of emigrating to the United States. In 1898, he arrived in Seattle, Washington, found work, and brought over “a picture bride” from Japan. Toyozo Sakura became one of the leaders of the Japanese-American community in the 1900s and a founder of the Japanese Baptist Church. By 1919, he and his wife had four sons and five daughters — all American citizens, born in the state of Washington. They had moved to Eatonville, a logging town where many Japanese worked in the mills of the Eatonville Lumber Company.

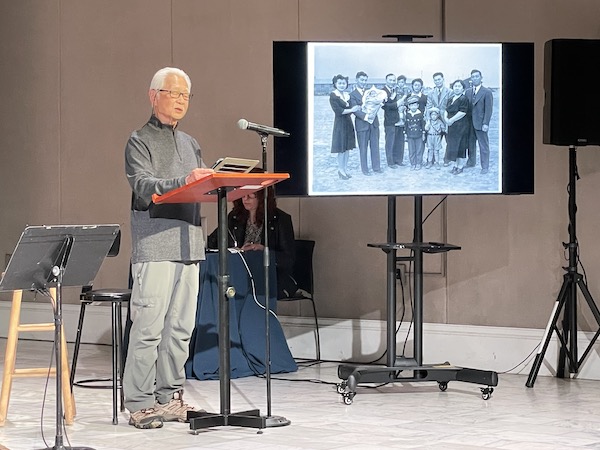

David Sakura in Shared Spaces. Photo: Helen Epstein

The second voice is Sakura’s father Chester, born in 1905. Nicknamed “Chet,” he attended high school in Eatonville and became a radio repairman, married, and had his own American children. “They had a vibrant life that you can see recorded on 8 mm film,” says David Sakura. Then, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which ordered all Japanese — including both naturalized citizens and those born in the US — to be deported from the West Coast. The Sakuras were taken to Camp Harmony at the foot of Mt. Rainier. From there, Chester Sakura began sending letters to the editor of the Eatonville Dispatch, which the newspaper published throughout the war and which serve as a source for Sakura.

The third voice is his. Born in 1936, he was almost six when he was fingerprinted by the FBI and given a number. He remembers that they each were allowed one suitcase, that his younger brother kept crying, and that his mother was upset by the soldiers. They were driven to Camp Harmony, a few miles down the road from Eatonville. But it was their deportation to Minidoka by train in September of 1942 that David Sakura recalls 80 years later, as “a nightmare.” They arrived in a hot dusty place with armed guards, watchtowers, barbed wire, one room for his family, and steel army cots on which they were told to stuff straw into bags for mattresses. The 2020 census counted 80 inhabitants in the town but during the war it housed 13,000 internees in about 600 buildings. (Minidoka, like other internment camps, bears the Native American name used by other forcibly displaced people.)

I was surprised to learn in Shared Spaces that when US Army recruiters came to Minidoka, Chester Sakura was one of the many Japanese men who volunteered to fight with the American military in Europe. David’s mother, aunt, and grandmother were left to raise the children in the camps. His mother, he narrates, crumbled from the stress and checked into the camp infirmary, leaving her children to the care of their grandmother. When the war ended, they heard that Japanese-Americans were no longer welcome in Eatonville. His family took a train east and wound up in Wisconsin, where eight-year-old David resumed his education in culturally German Milwaukee, playing the clarinet, listening to Wagner, and developing a love of classical music.

So much of Sakura’s narrative reminded me of the stories of other traumatized groups. Like many Holocaust survivors, particularly in the Midwest of the ’50s, David’s parents did not speak about their wartime experience, even though his father was now a returning GI. David remembers his father repeating a Japanese saying: a nail that sticks out will be hammered down. He taught his children to not speak up and not to stand out in any way. His mother did not talk about the war at all. “After the war, she was a changed person.” In his narration, Sakura incorporates her voice into a section based on letters from his aunt, who also kept silent about the war years until she wrote about them to her children.

As a young adult, David Sakura completed a doctorate in biochemistry and became a research associate at the Harvard School of Public Health before becoming a biotech investment banker. He began delving into his family history only in his early 40s, after his parents died. In 1979, the first Asian-American History month was declared at Boston’s Government Center and he began participating in consciousness-raising groups. Sakura took courses at the Harvard Extension school in Japanese literature. At about the same time, a reparations movement for Japanese-American internees began and, after a decade, The Office of Redress Administration began providing restitution payments of $20,000 to those subjected to evacuation, relocation, and internment during World War II. David Sakura found his name and internment number in the National Archives. He began to view his family’s experience during World War II as that of “canaries in the coal mine,” chillingly relevant to contemporary America.

The last voice in Shared Spaces is that of Dan Sakora, who grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, and worked in the Clinton Administration’s Department of the Interior for eight years. In 2001, he brought his father to DC to watch President Clinton sign into being the Minidoka National Monument. Now a Senior Advisor to the National Park Service, he sees preserving historic sites as a critical tool in combating racial hate and violence and is now fighting to keep the Minidoka National Historic Site from the encroachment of commercial interests.

During my interview with David Sakura, I suggested that he turn his script into a book, but he demurred. “I want Shared Spaces to be my legacy,” said the 87-year-old, who is a board member of the New Hampshire Music Festival and likes to fish as well as tend to his Japanese-style garden.

Helen Epstein is the author of Music Talks, Children of the Holocaust, the classic text on intergenerational trauma, and of ten other books of literary nonfiction.