Book Review: Bostonian Romance Novelist Emilie Loring — Once a Giant

By Martha Wolfe

The biographer makes her case with evident joy, drawing on wide-ranging research to supply a lucid, sympathetic homage to Emilie Loring’s indefatigable determination and sunny-side up literary sensibility.

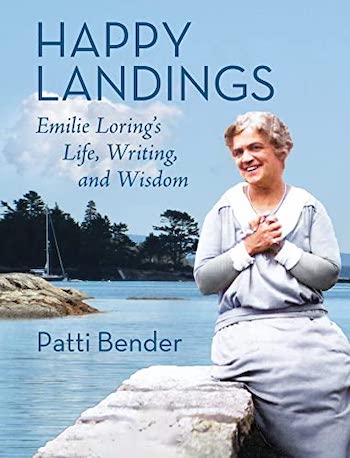

Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Writing, and Wisdom by Patti Bender. City Point Press, 637 pages.

How does an author who wrote 30 novels that sold over five million copies and were translated into nine languages, whose name appeared on best-seller lists alongside Pearl S. Buck, Sinclair Lewis, Faith Baldwin, and Agatha Christie, and who was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, fall into obscurity?

How does an author who wrote 30 novels that sold over five million copies and were translated into nine languages, whose name appeared on best-seller lists alongside Pearl S. Buck, Sinclair Lewis, Faith Baldwin, and Agatha Christie, and who was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, fall into obscurity?

Patti Bender supplies an answer in her admiring literary biography Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Writing, and Wisdom. Most readers have never heard of Loring, but millions once bought her novels. So what happened? Well, Loring didn’t believe that she wrote what many considered to be “romance novels.” She insisted her vision was “optimistic,” and that dependable emphasis on the upside did the trick. Loring’s obscurity among literary circles is linked with what once made her so popular. In her heyday, American readers liked their escapist fiction to be as unsurprising as it was uplifting. In Bender’s words, Loring’s books were “like a cardigan sweater — classic, comfortable, never too much or too little.” She was an author who invited her readers to “park their problems outside” the covers of her books and to “fare forth with me into the realm of imagination.”

Born in the shadow of the Civil War, Emilie Loring (1866-1951) witnessed two presidential assassinations, a worldwide epidemic, the Great Depression, and two World Wars during her lifetime. She was a Bostonian, a homemaker, a playwright, and a novelist. Loring came from a bookish family of publishers, comedic actors, and playwrights. Her grandfather published a penny newspaper that turned into the Boston Herald. Her father was an amateur dramatist whose 1876 play Among the Breakers is among the the best-selling amateur dramas of all time, selling more than a million copies. Loring began her writing life early in 1911 as a book reviewer. She used the pseudonym “Josephine Story” to evaluate books for the Boston Herald. She recommended books for young people as well as on current trends in homemaking, including Successful Houses and How to Build Them by Charles Elmer White, a Chicago architect who worked and studied under Frank Lloyd Wright. Two years later, the Star Company syndicated a series of articles by Josephine Story titled “How I Keep House Without a Servant,” which included advice for how to wash dishes: “Do it as quickly as possible and get it over with.” At the same time, Loring began to publish short stories under her own name. Emilie Loring wrote fiction; Josephine Story gave advice. Her first novel was published in 1922 when she was 56.

For her novels, Loring drew heavily on what was happening in her life and surroundings, though the everyday was poured into well-worn genres. “Home was a verb for Emilie Loring,” Patti Bender writes, “an active exercise of intellect, optimism, and creativity.” Her books were always laced with humor and dealt with love, romance, murder, and mystery. She wrote to entertain, hewing to respectable boundaries. Her books were “neither prudish nor prurient,” insists Bender.

A book a year for 30 years reflects her work ethic. Loring set a daily writing schedule and stuck with it. Rejection was not a part of her lexicon. She revised and resubmitted her short stories and novels over and over until they were accepted. William Penn Publishing Company published her first 15, Little, Brown and Company the remainder.

Her writing was steeped in an aristocratic, conservative Bostonian tradition, published for and read by women for whom suffrage was still a question mark. Loring’s husband, Victor, was a successful Cambridge attorney and they lived in Wellesley, a Boston suburb. The women’s clubs and the lunches and teas that she hosted in her own home did not inspire the satire meted out by contemporary Edith Wharton — they sparked her imagination. Still, chatting only went so far: “Talking of ideas doesn’t get one anywhere. No matter how brilliant or useful they may be, until they are formulated on paper they don’t count as creative writing. There is a little word of four letters W O R K which does the trick.”

Her writing was steeped in an aristocratic, conservative Bostonian tradition, published for and read by women for whom suffrage was still a question mark. Loring’s husband, Victor, was a successful Cambridge attorney and they lived in Wellesley, a Boston suburb. The women’s clubs and the lunches and teas that she hosted in her own home did not inspire the satire meted out by contemporary Edith Wharton — they sparked her imagination. Still, chatting only went so far: “Talking of ideas doesn’t get one anywhere. No matter how brilliant or useful they may be, until they are formulated on paper they don’t count as creative writing. There is a little word of four letters W O R K which does the trick.”

Against the backdrop of a worldwide flu epidemic and the “Great War,” Emilie Loring wrote about her own wartime experiences and those of her boys, who had trained for combat duty. In 1919 she was elected to the Boston Authors Club, an organization still in existence today. It is dedicated to “a fellowship where sympathy outdoes criticism.” She finished a 5,000-word story every two weeks, logging the word count and manuscripts’ destinations, mailing them away that very day. Revisions and resubmissions were completed speedily. In one three-month period, three of her stories and three articles were sent off 41 times before one was accepted. In Bender’s estimation Loring’s efforts at publishing were “like directing trains in Grand Central Station.”

Penn offered Loring her first contract for a full-length hard-cover novel in 1922, including a $250 dollar advance against 10 percent of the first five thousand copies sold. Newspaper ads called The Trail of Conflict, “a stirring love affair of the west … thrilling and dramatic.”

That January the Boston Authors Club heard Helen Sard Hughes of Bryn Mawr College speak about the current state of literature in America. Professor Hughes expounded that “literature of education” was to be preferred over “literature of delight,” condemning the flappers of the Roaring Twenties. Loring and two of her Boston Authors’ Club friends, who preferred to delight their readers with a little romance spice, thumbed their noses at this critic, who valued grimness over optimism. They dubbed themselves “Flapper’s Row” and went on with their writing. A friend of Loring’s husband arranged access for her at the Boston Athenaeum. There Loring found a quiet alcove of her own, going there each day “with her emerging draft, fresh paper, and two-dozen sharpened pencils.”

The post-WWI era saw a cultural rift in American culture. Some critics, H.L. Mencken among them, dismissed what they saw as the delusions of sentimentality. Loring’s The Trail of Conflict (“In the shadow of a sinister conspiracy, a courageous young heiress fights to save her marriage from certain doom”) was published the same year as Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. For Bender, Loring’s attitude “was less a matter of avoiding the negative and more that she was committed to the positive.” Loring defended herself this way in a Penn promotional flyer: “I am neither a super-optimist nor a Pollyanna, but behind the thickest cloud, behind the darkest situation, somehow, I sense the sun ready to break through. Why not? It always has.” Loring’s second book, Here Comes the Sun!, released in the spring of 1924, sold out of book stores in 10 days. Her publisher reminded the world that, “the public, not the editors, decide whether or not the author shall survive.”

The post-WWI era saw a cultural rift in American culture. Some critics, H.L. Mencken among them, dismissed what they saw as the delusions of sentimentality. Loring’s The Trail of Conflict (“In the shadow of a sinister conspiracy, a courageous young heiress fights to save her marriage from certain doom”) was published the same year as Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. For Bender, Loring’s attitude “was less a matter of avoiding the negative and more that she was committed to the positive.” Loring defended herself this way in a Penn promotional flyer: “I am neither a super-optimist nor a Pollyanna, but behind the thickest cloud, behind the darkest situation, somehow, I sense the sun ready to break through. Why not? It always has.” Loring’s second book, Here Comes the Sun!, released in the spring of 1924, sold out of book stores in 10 days. Her publisher reminded the world that, “the public, not the editors, decide whether or not the author shall survive.”

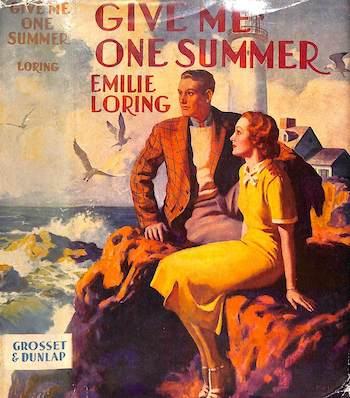

When the markets crashed in the fall of ’29, Loring survived and prospered. Her sixth novel, 1929’s Swift Water, was a huge success, even though its narrative dealt with “death, danger, and a crisis of the soul.” Penn began printing a second edition before the first was even released. By 1932 the Boston Globe was comparing Loring’s work to that of Thackeray, J. M Barrie, and Daphne Du Maurier. She became a dependable fixture on the Depression era’s list of best-selling authors. “Happy Landings,” a phrase she took from a congratulatory letter to Charles Lindbergh on the first anniversary of his trans-Atlantic flight, became her marketing catch-phrase. In 1936, Charles Shoemaker nominated her book Give Me One Summer for a Pulitzer Prize. Alas, that year’s award for fiction went to Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind. In the spring of 1938 her novel Today Is Yours, an English ghost story, outsold Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile during its first week of release. That year 61,642 copies of her novels sold in the US and abroad, a figure that would generate almost $400,000 in sales today.

Growing up in Arizona, Bender found Loring’s books “everywhere.” She is a fan, and has read each of the 30 novels several times. For her, Loring still has much to tell us about the trials and tribulations of the writing life, about women’s lives in the first wave of American feminism, about 20th-century history and politics. And the biographer makes her case with evident joy, drawing on wide-ranging research to supply a lucid, sympathetic homage to Loring’s indefatigable determination and sunny-side up sensibility.

Note: Patti Bender will speak at the Boston Athenaeum on May 16 at noon, and at the Wellesley Main Library at 7 p.m. on May 17.

Martha Wolfe is the author of the dual biography The Great Hound Match of 1905; Alexander Henry Higginson, Harry Worcester Smith and the Rise of Virginia Hunt Country (Lyons Press, 2015), nominated for the Library of Virginia’s 2016 People’s Choice Literary Award. She has published in the Boston Globe, Science News, Science Digest, and Bennington Review. Her essay “The Reluctant Sexton” won Honorable Mention in the Bellevue Literary Review’s 2018 Literary Contest. She is working on a biography of author Mary Lee Settle for West Virginia University Press.

Tagged: Emilie Loring, Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Patti Bender