Book Review: “War Diary” — When Dread Replaces the Everyday

By Preston Gralla

Ukrainian writer, artist, and photographer Yevgenia Belorusets’s diary blends the visceral with the mundane, showing just how quickly dread replaces everyday life.

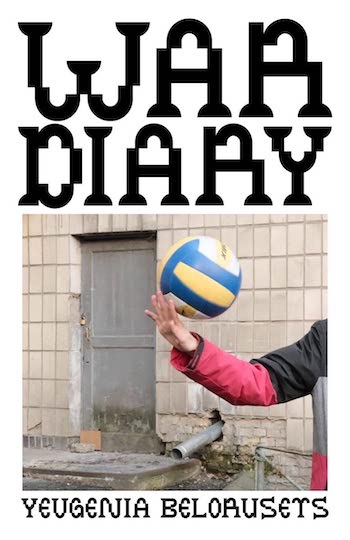

War Diary by Yevgenia Belorusets. Translated by Greg Nissan. 140 pp. New Directions. Paper, $16.95

Russia’s war against Ukraine grinds on after more than a year, Tweeted and Telegrammed, parsed on YouTube channels with street-by-street maps of the day’s fighting, videos posted everywhere of drones destroying tanks, missiles taking to the sky like hopped-up angels of death, bombs descending in balletic slow motion. Watch enough of them and they begin to look like archival footage of grainy, low-res video games from decades past.

Missing from it all is the domestic side of war. What’s it like trying to get a latte when your city is under missile assault? How do you do your grocery shopping when death may rain down at any moment? What does it feel like to wake at 7 a.m to the sound of air raid sirens? When all normalcy is destroyed, do you still have to pay your electric bill?

You’ll find out in War Diary by Ukrainian writer, artist, and photographer Yevgenia Belorusets, a personal account of the first 41 days of the war spent in Kyiv. The diary was published online by Isolarii, in print in the German newspaper Der Spiegel, and was adapted for This American Life. (This is her second book translated into English; she’s also the author of a short story collection about the earlier Russian invasion of Donbas, Lucky Breaks. Go here for the Arts Fuse review.)

The diary blends the visceral with the mundane, showing just how quickly dread replaces everyday life. It also captures Belorusets’s disbelief that the world would let something this horrific happen.

The war starts for her with eight missed early morning phone calls from her parents and friends. Why so many, Belorusets wonders? She thinks: There’s been an accident, in Kyiv, maybe a big one. So, she calls a cousin and hears: “Kyiv has been shelled. A war has broken out.” Her initial numbness at the news gives way to anger at the world for allowing the war to happen — a theme she returns to time and time again throughout the diary.

At first, Kyiv is spared much of the missiles and air strikes, but city life still changes dramatically. The streets are largely empty. People occasionally go outside to hunt for the basics of everyday life, but for little else, fearing they will be targeted next.

Then comes an increasing number of explosions inside the city. By the end of the first week, Belorusets writes, “You can tell a story about the war on every street corner.” Most intersections are guarded by the armed forces. Saboteurs increase their attacks. The reality of the war hits home in odd ways. A neighborhood barista, known for the beautiful swans he painted with milk foam, shows up one day as a soldier.

To survive, she turns to magical thinking and dark, bitter humor. One morning Belorusets wakes up unaccountably jubilant. Why? Because, she writes, “I no longer believe in the war! It simply can’t be.… It isn’t true. What neighboring country bombs a city to rubble in the twenty-first century?”

Jubilation quickly fades and reality returns, turning into fear. Later that day Belorusets meets a famous photographer and her friends who have come to Kyiv to document the conflict. She writes, “Uneasiness quickly washed over me; I realized that isn’t a good sign when a well-known war photographer and her entourage set up shop in your city.”

And so it goes, week after week, the damage worse as each day passes. Soon war changes even the way she experiences time and distance. “The horizon,” she writes, “is suddenly closer. The Kyiv hills, the asphalt, the courtyards of the building — everything is invited to join the war.” As for time: “These days it’s hard to grasp tomorrow. Tomorrow seems an eternity away, as if it were happening on another planet. One can imagine tomorrow in theory, but not as a moment in one’s own passage of time — only as a story one tells oneself.”

Photographer and author Yevgenia Belorusets. Photo: Olga Tsybulska/New Directions

War eats everything. The simple act of paying utility bills becomes strange. She gets a note from the electric company: “Many Kyiv utility workers joined the Ukrainian army and are now fighting for our freedom. But it is still important to settle the bill.”

Although all wars are brutal, they change with the times, and Belorusets documents that as well — a destructive attack that reduces a huge apartment building and shopping mall to rubble was launched because a TikTok video had inadvertently disclosed the location of Ukrainian tanks. The Russians targeted them, but by the time the attack began the tanks had already moved on.

She finds solace in the simple, the everyday: cleaning her apartment regularly to give life a sense of normalcy; buying fresh bread in a neighborhood bakery; reveling in Kyiv’s beauty, its broad avenues, beautiful houses, gardens, and sculpture parks.

A photographer, she documents the war, steering clear of death, rarely showing destruction. At first, she portrays only the eerie emptiness of the city’s streets. Later, most of the photos are of people celebrating the mundane in a time of war: A young woman, the epitome of hope, arms filled with a bouquet of early spring tulips; an elderly man and woman posing with their two chihuahuas; lovers embracing; a smiling woman soldier so at ease she seems out for a leisurely stroll, her rifle hanging from her shoulder as if it were a handbag. Life, even during war, goes on.

After 41 days she leaves the city for Warsaw and Berlin, and ends the diary. Three months later she resumes it briefly from Berlin, writing “When you leave a war zone, you take a piece of it with you, as if by accident. This something remains glued to your life for a time, a souvenir you drag along and simply can’t get rid of.”

The same can be said of this book. You may close its pages, but you’ll never rid yourself of what you’ve read and seen.

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.