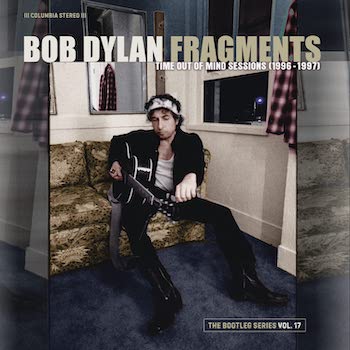

Music Album Review: Bob Dylan’s “Fragments” — Appreciating the Enigmatically Ruminative Vibe of “Time Out of Mind”

By Matt Hanson

I’ve always admired Bob Dylan’s resolute reluctance to repeat himself, artistically or otherwise. The Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments reminds us how obsessive that aesthetic restlessness really is.

“I thought I’d be seeing Elvis soon,” joked Bob Dylan after a period of frighteningly ill health in the mid-’90s. It’s a pretty good line — wry, world-weary, and yet imaginative — that suggests something about his mental state as he was working on 1997’s Time Out of Mind. Hailed as a return to form when it was first released, the album sounds like the work of someone who had recently come back from the edge after finding a way to keep themselves going. Also, a word of advice: some records only reveal their true mise en scene when played at night, assisted by the immersion of headphones. Time Out of Mind is one of them.

“I thought I’d be seeing Elvis soon,” joked Bob Dylan after a period of frighteningly ill health in the mid-’90s. It’s a pretty good line — wry, world-weary, and yet imaginative — that suggests something about his mental state as he was working on 1997’s Time Out of Mind. Hailed as a return to form when it was first released, the album sounds like the work of someone who had recently come back from the edge after finding a way to keep themselves going. Also, a word of advice: some records only reveal their true mise en scene when played at night, assisted by the immersion of headphones. Time Out of Mind is one of them.

The Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments is the handsome and expansive five-disc collection of songs from that session. It offers a new mix of the record, one that is more in line with Dylan’s initial wishes. There are also several discs’ worth of (sometimes confusingly labeled) alternate takes, as well as other Dylan tunes from the period that (eventually) appeared elsewhere. The package concludes with a compilation of various live versions of tracks on Time Out of Mind. I’ve always admired Dylan’s resolute reluctance to repeat himself, artistically or otherwise. Fragments reminds us how obsessive that aesthetic restlessness really is.

Dylan effectively rewrites everything he’s done night after night, song by song, in and out of the concert hall or the studio, testing the internal strength of what might have been written years ago. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he doesn’t treat his material as if he is serving up reheated pizza. His approach is more respectful: he is holding rare minerals carefully up to the light, catching fresh new angles and glints in the process.

Take, for example, the song “Can’t Wait,” of which there are no less than seven versions presented here. I think the final recording is ultimately the best one, a sexy, slow whirl of guitar and drums, but it’s interesting to see how it evolved. First it was treated as a plaintive, minimalist, organ-based first-person address about romantic angst: “Life is short and I think about her a lot/ I can’t say if I want the pain to end or not.” Then you click on a different version, and hear that it has been pushed into a loping, piano-driven groove. Click again, and it has settled into a slightly different version of the final cut’s slow, drum-centered strut. Each one of these takes would be a perfectly respectable official release. Yet, when you sit back and hear the final version, you shake your head in wonder because you can appreciate the path that was taken to reach the final version.

The problem you run into with extensive box sets like this is that, in the effort to be comprehensive, a lot of inessential material is included. Thankfully, this isn’t the case with Fragments — at least not quite. Most of the tracks here justify their inclusion, with some exceptions. I like having it but, to be honest, the new remix of the record is not substantially better (or even THAT remarkably different) than the initial release, which is much murkier and swampier, with just the right amount of space left between each stately, brooding note. Producer Daniel Lanois’s hushed ambiance, possibly a result of recording in a tiny, antique-filled Miami studio, enhances the record’s vibe of fatigued, stoic persistence.

And the live version of the record is good, but does it fundamentally change my understanding of the music? The way the outtakes do? Not really. No doubt there was an embarrassment of riches to pick from, given the staggering number of concerts Dylan’s played and the extensive bootlegging. So why these specific cuts? Do we necessarily need several versions of the overlong, crabby “Highlands” featuring an extensive and rather pointless Curb Your Enthusiasm-esque interaction with a judgmental Boston waitress?

For all its existential resignation, Time Out of Mind is not at all a drag to listen to. If anything, it’s more compelling because it resolutely stays within its enigmatically ruminative vibe. In terms of the album’s lyrics, it often doesn’t sound like Dylan’s having a very good time with things in general. He’s not brimming over with joy at having been issued a new lease on life in his mid-50s. There are plenty of lines that point to some kind of emotional desperation brought on by a breakup — “I’m sick of love/ I’m love sick” claims the brooding first track, a lament right out of Hank Williams. But if you think about it, the lines are not just witty wordplay — those are two rather different sentiments, aren’t they? I once wondered aloud to a friend of mine if Dylan really has had his heart broken all the times it would take to inspire those songs written over all those years. Or is it just a literary device? He thought for a minute and said, no, I think he’s just an old soul. I suspect that we’re both right.

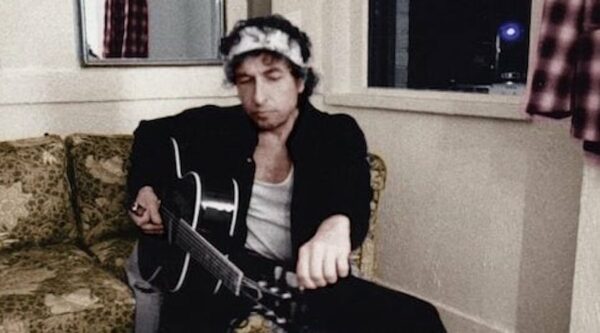

Bob Dylan at the time of the Time Out of Mind sessions. Photo: Columbia Records

You can bask in the devoted, loving warmth of “To Make You Feel My Love,” which has been given the called-for torch song treatment by Adele and others. (The tune is a world away from the bitter lovelorn distance expressed in “Million Miles” and “Standing in the Doorway”). A full-throttle line like “I’d go hungry, I’d go black and blue/ I’d go crawling down the avenue/ No, there’s nothing that I wouldn’t do/ To make you feel my love” deserves to be belted out in grand, show-stopping style, and that isn’t a natural fit for Dylan’s vocal range. The rare outtakes “The Water Is Wide” and “Red River Shore” display how he can still drum up romantic passion, just in a more modest register.

In the utterly poignant “Not Dark Yet” Dylan’s wizened rasp nails the angst of the line “feel like my soul has turned into steeeeeel.” Somehow he can infuse his cynical, time-worn fatalism with vitality. He pulls that off when he murmurs “he’s not looking for anything in anybody’s eyes” or that “behind every thing of beauty there must be some kind of pain” or that he “can see what everyone in the world is up against” or about being left “standing in the doorway crying, blues wrapped around my head” To borrow an earlier phrase of Dylan’s, he’s not selling any alibis. “When you think that you’ve lost everything, you find out you can lose a little more/ I’m going down the road feeling bad/ Trying to get to heaven before they close the door.” Yes, he is making easy wisecracks about how humanity has been dealt a bad hand as he revels in the stoic resignation of ancient blues songs. But Dylan’s still raising his weary eyes to the skies. There’s something uplifting about that.

Musically vibrant yet lyrically downhearted, Dylan’s stellar late-century run of Time Out of Mind, Love and Theft, and Modern Times figures in a pet theory of mine. I can’t help but compare this burst of energy with Philip Roth’s roughly contemporaneous trilogy I Married A Communist, American Pastoral, and The Human Stain. Controversial yet canonical, both are Jews from humble backgrounds who rose to prominence by looking deeply into what one Roth character once called “the real American crazy shit.” Time Out of Mind is the curtain-raiser on a series of records imbued with the late-life themes of mortality, romantic loss, and trying to find a place in a world way out of joint. Quite a lot to take on, even for someone like Dylan, and that was more than a quarter of a century ago.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in the American Interest, the Baffler, the Guardian, the Millions, the New Yorker, the Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.

Tagged: Bob-Dylan, COLUMBIA RECORDS/LEGACY RECORDINGS, Fragments, Matt Hanson

Wow! Nailed it. You articulated what I have been feeling/trying to understand about a great deal of Dylan’s work. Thanks, I appreciate the help and your perspective!