Book Review: One More Round with Norman Mailer

By David Daniel

In his centennial year, it’s difficult not to see that Norman Mailer’s literary standing is at an inflection point.

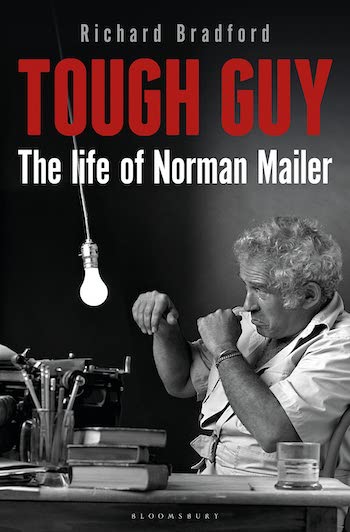

Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer by Richard Bradford. Bloomsbury Caravel, 294 pages, $28 (hardcover).

In his 1959 jumble-sale prose collection Advertisements for Myself, Norman Mailer issued his contemporaries a challenge: Papa Hemingway was in decline (he would die by self-inflicted gunshot two years later), so Mailer decided it was time to crown himself the new heavyweight literary champion. His stated goal was to foment “nothing less than … a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” The connection any of this self-marketing had with reality is debatable now. History and changing social mores have tarnished Hemingway’s standing, but he endures as a cultural icon. As for Mailer’s impact on his and our time, it falls short of “revolutionary.” But there is no doubt that he threw a battery of stylish and incisive punches — some landing, some not — at many of the issues that gripped America in the second half of the 20th century — the post-World War II global realignment, the Cold War, Viet Nam, Civil Rights, and the Women’s Movement among them. Mailer was nothing if not a cocky pugilist, as a thinker, gadfly, participant, and, most important, literary chronicler.

In his 1959 jumble-sale prose collection Advertisements for Myself, Norman Mailer issued his contemporaries a challenge: Papa Hemingway was in decline (he would die by self-inflicted gunshot two years later), so Mailer decided it was time to crown himself the new heavyweight literary champion. His stated goal was to foment “nothing less than … a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” The connection any of this self-marketing had with reality is debatable now. History and changing social mores have tarnished Hemingway’s standing, but he endures as a cultural icon. As for Mailer’s impact on his and our time, it falls short of “revolutionary.” But there is no doubt that he threw a battery of stylish and incisive punches — some landing, some not — at many of the issues that gripped America in the second half of the 20th century — the post-World War II global realignment, the Cold War, Viet Nam, Civil Rights, and the Women’s Movement among them. Mailer was nothing if not a cocky pugilist, as a thinker, gadfly, participant, and, most important, literary chronicler.

In a career that spanned six decades, Mailer published over 40 books, including 11 bestsellers, and won two Pulitzer Prizes and a National Book Award. Less successfully, he wrote and directed films and ran for political office. His prolific self-advertisement made him the most publicly recognizable writer in America. Part of that notoriety came from his appetite for controversy and scandal, the latter including spousal abuse and instigating violent feuds with fellow authors and critics. Now, 16 years after his death at the age of 83, in time to mark the centennial year of his birth, comes a new biography to gauge the accomplishments and the carnage.

Readers anticipating a big, deeply researched and newly considered life of Mailer are going to have to wait. Biographer Richard Bradford has something else in mind. Coming in at just under 300 pages and titled Tough Guy, the book features a jacket photo of Mailer at his desk, hands raised in a boxer’s pose, a swinging overhead lightbulb standing in for a punching bag. This is a book with an attitude about a writer who made a career of projecting attitude. Bradford doesn’t burn space, as biographers tend to, with long genealogies of their subjects’ forebears. We get just enough necessary background: Mailer’s supportive family, with doting mother and gambler father, and an impression of a precocious Norman who goes from public schools in Brooklyn to Harvard university at age 16 intending to pursue aeronautical engineering.

What follows is an engaging account of his discovery at Harvard of literature and a talent for writing. He wrote for the Advocate and, as a junior, won a national magazine’s fiction prize. Early on he displayed his flair for nonconformity and ego-driven ambition. When the war came, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, he determined that the South Pacific theater might afford the better opportunity for writing material and after graduation wound up in the army. On the IQ test after recruitment he scored 166 (145-160 was generally regarded as the highest-possible level of attainment). He was deployed to Luzon in the Philippines in December of 1944. By then he was married (for the first of six times) and, as Bradford notes, his detailed letters home, which he insisted his wife keep, were “a rehearsal for his career as a shifty literary narcissist.”

The narrative moves across now-familiar terrain, chronicling how the publication of his novel The Naked and the Dead in 1948, at age 25, was greeted with immediate and immense critical acclaim. Mailer became the most outspoken of the talented crop of post–WWII literary writers. But reprising the success of a first novel has been a stumbling block for many authors, and it was for Mailer. His next two, Barbary Shore (’51) and The Deer Park (’55) were almost universally panned. Stung by their failure (but not humbled; if anything he became more pugnacious), he turned to alcohol and marijuana as a means to move forward creatively. Rather than return with yet another novel, he published a miscellany of essays and short stories, the aforementioned Advertisements (’59), with its bumptious posturing and body blows leveled at his peers. Fellow contenders included James Jones, Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, and William Styron — some 20-odd in all, whom he names as possible heads for Hemingway’s crown before determining he’s the money-on favorite.

In terms of the New York literary intellectual axis, filled with a formidable battery of editors, writers, and critics (Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Diana Trilling, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Gore Vidal, and many more), Mailer was both insider and outsider. He was a celebrity, his opinions sought, his essays and editorials (he was writing little pure fiction now) welcomed in magazines and journals — Commentary, Commonweal, Harper’s, Partisan Review, and others, including alternative mags such as the Village Voice, which he co-founded. (Notably not the New Yorker. A story, not reported in Tough Guy, has it that Mailer proclaimed he would not send work there because they wouldn’t let him write “fuck.”) Craving fame, he sought controversy and courted media celebrity — often catching the eye of attractive women. This latter was a fact Mailer exploited throughout his life through numerous affairs, irrespective of his usually being married at the time.

Throughout the ’50s into the ’60s, Mailer’s distinctive syntactical prose style emerged: a convoluted hybrid of fiction and journalism, with ideas coiling tight like springs about to pop, and a fondness for visceral metaphors. Cancer, boxing, warfare, scatology, and orgasm are the frequent filters through which he addressed all manner of subjects: American culture, existentialism, authoritarianism, politics, boxing, feminism, celebrity, and more.

In the late ’60s he continued his drift away from the traditions of the novel form and produced the rebellious nonfiction of The Armies of the Night and Miami and the Siege of Chicago (both ’68). The former won a Pulitzer and a National Book Award, but these were critical rather than commercial successes. They established him as one of the “New Journalists” and cemented his position as a preeminent man of letters and peripatetic commentator on almost everything. In 1979, in a further refinement of his blending of fact with fiction, he published The Executioner’s Song, a 1,000-page true-crime novel that earned him another Pulitzer.

Despite being one of the best-paid writers in the world in advances and royalties, most of the incoming dollars went to multiple alimony payments, child support, the IRS, and a high lifestyle. Debt forced him to produce books, often undertaking dubious projects he would more wisely have avoided. He was continually going on about producing the “big novel” he had long promised (and been paid for). What we got were epic scatological fizzles like 1983’s Ancient Evenings. His situation became, as Bradford describes it, “a literary life sentence.”

Tough Guy focuses on the unsavory elements of Mailer’s behavior, and Bradford pulls no punches. He identifies Mailer as a brawler, a wife abuser, and a “serial fornicator,” unfaithful to every one of his six wives. What was considered Mailer’s intellectual daring at the time brought energy and excitement to his work, but today many of his ideas and proclamations don’t bear close scrutiny. Bradford calls out “The White Negro” (’57), An American Dream (’65), and Why Are We in Vietnam? (’67) as works whose swashbuckling rhetorical contortions smokescreen mushy thinking. He decries Mailer’s self-delusion that he was a voice for radical ideas when often he was only being incomprehensible. And, like Hemingway, Mailer could easily tip over into unintentional self-parody, particularly as he became older.

Much of Tough Guy is a retell of the known, drawn from secondary sources, including earlier biographies, rather than a deep new probe of Mailer archives. Do we need a retread? It’s been a decade since J. Michael Lennon’s 900-page authorized bio A Double Life (2013) and Peter Manso’s oral history Mailer: His Life and Times (’85) had come along before that. Plus there have been a slew of other books, produced while, and after, their subject was alive and writing. It appears that time and shifting public attitudes have caught up with Mailer — he is our contemporary in some ways and a distasteful anachronism in others. One expects in the future larger, more deeply researched, and better orchestrated excursions into Mailer’s outsized life and work.

Still, for now, Tough Guy is a Cook’s Tour that’s much worth taking. Bradford is a fluent narrator and provides a useful refresher on the salient details of a long and interesting life. Tough Guy will satisfy salacious appetites as it explores Mailer’s relational dynamics and sexual proclivities, his alcohol and drug use, his penchant for fisticuffs. And he reminds us of the scattershot choices of a career that became increasingly driven by the need for a paycheck. The biographer offers a number of fascinating side trips — the admissions policy for Jews in the WASP-centric Ivy Leagues in the ’40s; the internecine ideological conflicts that beset the Old Left in the dark wake of Stalinism; the launch of the Village Voice as an alternative to the existing cultural infrastructure in ’50s New York. Yet through it all the narrative maintains its forward movement via a chronological approach that is brisk and keyed to the succession of Mailer’s works.

Norman Mailer in 1988. Photo: Criterion Collection

Bradford, who is British, displays a bit of the pebble-dasher’s fondness for erudition, finding opportunities to use words and phrases like “demobbed,” “de trop,” and “déclassé.” He is, after all, a university research professor, whose previous work includes bios of George Orwell, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, and Alan Sillitoe, all Brits. He has also penned a “controversial portraiture” of Patricia Highsmith. At times a subtle sensationalist taint is discernible and we are only a few canny turns away from a Fleet Street tabloidist. Still, he is smart and fun and a bit outrageous to read, with a knack for summary observation, as when he notes that Mailer’s “ambition to change the world according to his private compulsions was as much the driving force as anything resembling an artistic vision.” And, when he concludes that Mailer’s life “comes as close to being the great American novel; beyond reason, inexplicable, wonderfully grotesque and addictive.”

In his centennial year it’s difficult not to see that Mailer’s future literary standing is at an inflection point. Yes, Library of America has published some Mailer texts: Four Books of the 1960s (An American Dream | Why Are We in Vietnam? | The Armies of the Night | Miami and the Siege of Chicago), Collected Essays of the 1960s (Selections of Mailer’s prose from the collections The Presidential Papers, Cannibals and Christians, and Existential Errands), and The Naked and the Dead. But will they go beyond 1972? Overall sales numbers for Mailer’s books are unimpressive, and he isn’t talked of much in university classrooms or book groups, aside from being set up as a tackling dummy in American feminist history courses. Nevertheless, a sizable amount of his work is in print (The Executioner’s Song does well), new anthologies of his writings are being released (the most recent is A Mysterious Country: The Grace and Fragility of American Democracy), and there is active ongoing scholarship. One assumes his executors and heirs are doing what they can to fan his flame. Will the grand legacy he saw for himself — heavyweight champion! — come true? Or is he fated to be an also-ran? Efficient and gossipy, Tough Guy does ample justice to Mailer the charismatic self-marketer, one of the baddest of the bad boys of postwar American literature. Will it make his books any more appealing? The final bell has yet to ring.

David Daniel’s newest book is Beach Town (Loom Press), a collection of stories set on Boston’s South Shore. He teaches part-time at UMass Lowell and can be reached at daviddaniel67@gmail.com.

What a great review. I read another review of Tough Guy recently and didn’t come away with half as much. Love the ending, too.

Great review.

The general discussion of a writer’s staying power reminds me of Shelley’s poem, Ozymandias.

Or as Kansas put it, “We’re all just dust in the wind.”

Excellent review! I’m not sure Bradford has earned it, but Mailer deserves it. Writers, all of whom are complicated, don’t come much more intwined in their age than Mailer, and this review is a brilliant little snapshot of his tortured engagement.

I confess that I can’t name a single Mailer work because of his penchant for writing about “[c]ancer, boxing, warfare, scatology, and orgasm .” But Dave’s review of Tough Guy is enough to make me want to read it, perhaps to sidle up to reading Mailer, but definitely because Dave says “he is smart and fun and a bit outrageous to read.”

Now about the brilliant last line of this review? Solid Dave Daniel gold.

I’d rather read Dave Daniel’s insightful and incisive review of the new Mailer biography than anything the bombastic New York bully wrote in his own hand. (True story.) An honest and humble craftsman Dave Daniel’s soul shines through in his commentary while Mailer’s egotistical & dismissive musings are dead on the page.

Tim Trask is right.

Jay Atkinson is right. Maybe someday, Dave’s unique niceness as it come across on the page will get proper exposure. The world could use it.