Music Interview: Arlo Guthrie on Returning to the Stage and Being Banned in Boston

By Noah Schaffer

“My core values have not changed — I’m still me and I’m still for the average guy. People can be swindled and people can be fooled. You have to bear with them and help get them through it.”

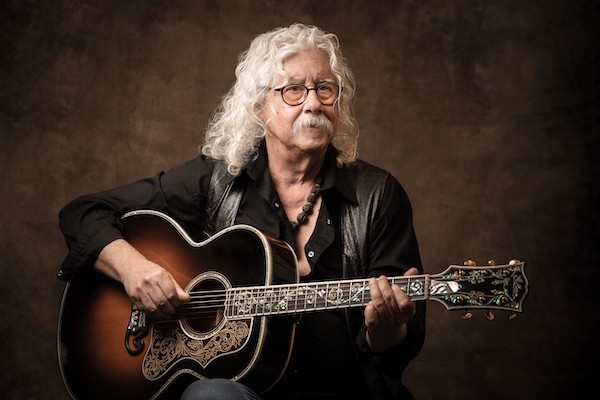

Arlo Guthre today. Photo by Eric Brown; courtesy of the artist.

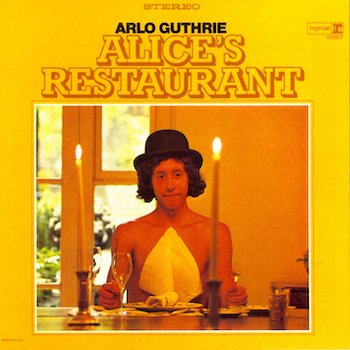

When the live music business was on hiatus in 2020, a number of veteran performers announced that they wouldn’t be returning to the stage even when it was allowed. One of them was Arlo Guthrie, whose retirement announcement signaled the apparent end of a career that saw him make “Alice’s Restaurant” famous, play Woodstock, achieve some surprising commercial airplay with “City of New Orleans” and “Coming into Los Angeles,” tour relentlessly (often with Pete Seeger), and, in recent years, see his children and grandchildren continue the Guthrie troubadour tradition.

But the retirement didn’t last long. This weekend at the Boch Center’s Shubert Theater Guthrie kicks off a four-city tour called Arlo Guthrie: What’s Left of Me, which finds him in conversation with author and curator Robert Santelli. It’s also the opening of a new exhibit about Guthrie called Native Son at the Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame, which is housed in the Boch Center. The exhibit runs through August. I called Guthrie at his longtime Berkshires home to talk about these upcoming performances as well as some old memories.

The Arts Fuse: What’s retirement been like after so many years out on the road?

Arlo Guthrie: The main feature of it has been not going anywhere. Up until two years ago I was going somewhere most of the time at least nine months a year; then I was going fewer times until I said “This is crazy, let me just take it easy from now on.” So retirement for me was just staying put.

AF: Have you been writing songs at all?

AG: No, I wrote a lot of stuff when I was younger. I’m open to it, but songs don’t originate within me, they come through me, so I’d be perfectly happy writing songs if they want to show up, and if they don’t I’ve learned to be happy with that.

AF: What made you want to come out of retirement and do these Q&A shows?

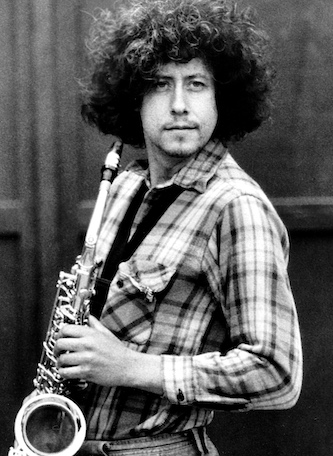

Arlo Guthre in 1979. Photo: Wiki Common

AG: It was a few things. The first thing is that my singing voice had reached a point where I wasn’t comfortable with it, but nevertheless over the years I’d also been a prolific storyteller in between the songs. So although I can’t sing like I used to, I can still tell some tall tales. That hasn’t diminished at all. So the rationale for going back to work was redefining who I was and what I was able to do, and to do it in a way that would be fun for my friends and me and my world, and I think we’ve managed to do that.

AF: Is it just an interview, or will you be bringing your guitar?

AG: I might bring a guitar, but it’s not a musical event, it’s mostly a conversation and an opportunity to see my friends and fans again and show up and see what happens. This is new for me — I’ve never done anything like this. All I know is I’ll be there, and by the looks of things, so will a lot of other people, and I’m thrilled about that!

AF: Do you have any involvement in the exhibit? Did finding these items that are in it, like your first guitar or early song lyrics, bring back any particular memories?

AG: It’s some of my stuff, but beyond it being my stuff I didn’t really curate the exhibit, so I don’t know what’s there. I know my daughter Annie is picking up some instruments and heading to Boston today, but some of it was in Tulsa when they did an exhibit of mine at the Guthrie Center there. Then it went into storage and now some of it is making its way to Boston. If there’s interest in it, terrific, and if there’s not, that’s okay too! Most of it is from my former life as an entertainer, and for people interested not just in me but in the times in which I participated, it might be of interest. I was present at a lot of the important events that took place over the last 50 years. If some of it is there, it’s fine to put on exhibit.

AF: Certainly one of those important events was Woodstock. Over the years there have been a number of attempts at having Woodstock reunions or anniversary shows. Some of them never even got off the ground, and the ones that did certainly didn’t capture the spirit of the original event. Why do you think that is?

AG: The obvious conclusion is they weren’t free! The fun part for me on the 50th anniversary of that event was doing a free [song] at the original site. I had a great offer from Michael Lang … which I turned down. What made Woodstock historic and why we’re still talking about it is that it turned out to be a free event. Even if it was not organized that way, what made it special was the spirit of people who were willing to lose their vested interests in order for there to be a successful event, and by successful I meant safe and fun, and I think they succeeded. And they made their money back with the records and movies but they took a bath on the event itself and I think that’s what made it historic.

AF: The exhibit is called Native Son — a play on your longtime record label “Rising Son.” How has living all this time in the Berkshires impacted your music and career compared to if you’d stayed in New York or been based somewhere like L.A.?

AG: Well, if you’re on the road nine months a year it doesn’t really matter [where you are based], what matters is when you’re not on the road working and touring. I found the Berkshires to be a lovely place for that, and I’ve been here a very long time. If it was not my first gig, my second was at Club 47 in Boston, which is now Passim, so I’ve got a long history of being in the state. I hope to remain here as long as I can. Back then Club 47 was no different than playing Passim later on! It was the same little place, an odd little place, but they do great stuff there and have great outreach programs, which they’ve always had. Back in 1966 when I first played there for me it was one of the major hubs in the wheel of the folk music world.

AF: And it still is.

AG: That is because the folk music world has shrunk to a size and an interest that is somewhat akin to what it started out to be back in the ’50s.

AF: On that note, earlier you mentioned your life as an “entertainer.” In folk there’s this tension or dichotomy between being an entertainer and being an artist…

AG: Well, I come from a long tradition of people who made music. Some made it worthwhile — they could do it as a lifestyle, others made music for fun and did it sitting around after a real job. My grandfather or my grandmother on my mother’s side wrote poetry and songs, not because it was commercially viable but because they loved it, and I grew up in that tradition. Now don’t get me wrong, there was a time when it was great to be commercially successful, but that was never the object of the exercise. It was always fun and I think it still is for a lot of people, which is why they’re out there playing little places and putting out YouTube videos of their stuff. And there isn’t the audience that there used to be as far as big record companies and entertainment industries are concerned, but there’s always been just enough of a critical mass for it to be fun and worthwhile for those who are good at doing it.

AF: This talk of your family tradition of course leads us to your father Woody. I think the first of your father’s songs that you recorded was “Oklahoma Hills…”

AG: When I first began singing in 1965 or 1966 a lot of people came to hear Woody Guthrie’s kid. I was happy to be able to sing his songs for them. I also had a younger audience who, like a lot of people, had to learn who Woody Guthrie was, so I was able to put my own stuff out there. Over the years I’ve always included my father’s songs in all of the shows that I’ve done. Depending on what is going on in the outside world a lot of those songs and insights still ring true, those insights he had 60 to 70 years ago still have some magic and authority, and for that I’m grateful.

AF: What about “Oklahoma Hills” made it the first of your father’s songs that you recorded?

AF: What about “Oklahoma Hills” made it the first of your father’s songs that you recorded?

AG: The fun part is, my dad, contrary to a lot of folk enthusiasts’ knowledge, tried to be commercially successful as well as honest. That’s a tough row to hoe. “Oklahoma Hills” is a song he had written and his cousin Jack recorded. [Woody] was in the Merchant Marines in World War II, and he came into a port in New Jersey, went into a bar, and heard that song on a jukebox. No one had told him, or he hadn’t gotten the news that it had been recorded and was a big hit. So he just kept putting nickels in the jukebox, saying, “That’s my song!” There’s a sense of humor about it that intrigued me as well. His cousin Jack added a hillbilly rhythm and sensibility that was really good. I think my father took that to heart and so have I. Jack Guthrie was one of my first heroes and I’ve played his records over and over again, going back to when they were 78s! A lot of his work has been reissued by Bear Family in Germany, and I think it’s great that his work is still alive and well.

AF: You said you’ll be telling some tall tales, and there are a few I’ve heard over the years. One is that when your dad passed away the container with his ashes wouldn’t sink in the Long Island Sound…

AG: It was out in Coney Island — it was in the Atlantic Ocean. His ashes were in a can, and we had brought them to be scattered in the Atlantic with my older sister Cathy. That was his wish and we wanted to honor it, but none of us had remembered to bring a can opener! So we couldn’t open the can! So we somehow found a church key and opened the can that way, puncturing the top in a circle, hoping that would be enough. It took a long time for it to sink!

AF: Another is that “Alice’s Restaurant” was originally something you performed a few times on Bob Fass’s show on WBAI. Did the song change a lot?

AG: It was essentially the same song, and I did record it for WBAI, which was a local station in New York, and I went up there — and I didn’t know they were recording me, by the way — and when I went home that evening they had gotten such a response to it that they said “we’ll play the song if we get such and such amount of donations.” So they raised money by playing it until they were playing it all the time! And eventually they decided that if you paid us a certain amount of a donation they’d stop playing it. So I made money for them both coming and going! [laughs]

AF: In the song you recount being told at the draft office to go sit on the Group W Bench. It’s so famous that during Covid you held some online Group W Bench Sessions. That raises the question: What did the W stand for?

AG: I have no idea! Actually, I’ve been informed a few times, but I’ve forgotten! But if you had some form of illness or they were considering your worthiness — but the W doesn’t stand for worthy — it’s where you went so they would evaluate you further. I was sent there, and the place was really called that. Now it has become a phrase that means something to a lot of people, and I’m happy about that.

AF: You mentioned being known for what you say in between songs. Someone else like that who is still with us is Ramblin’ Jack Elliot.

AG: Jack was at my house when I was four or five, or even less. At first Jack was just an older person to throw toys at! Jack remembers that fondly, but as the years grew our relationship changed, and he’s still out there; he’s 91. We’re still in contact all the time and we’re friends now. He’s not an uncle or babysitter — if anything, it’s the other way around. I really care about the man, and we’ve had opportunities to get together. And I’m really thrilled he has become a lifelong friend, and I mean lifelong. I’m in my 70s and I met him when I was three — that’s over 70 years!

AF: While we’re talking about the songs of your family, are there any songs by any of your children that have resonated with you recently?

AG: They’re all doing their own things and all do them differently. Abe came of age in the glam rock era so his songs are a bit more like that; my daughters are a bit younger and they grew up in another era, so they reflect them. Maybe they’re not very commercially successful, but they held onto the tradition of doing their own thing, and for that I’m thankful and blessed beyond measure.

Arlo Guthrie with the Thüringer Symphoniker, conducted by Oliver Weder. Photo: Wiki Common

AF: In recent years you’ve seemed to resist being pigeonholed politically. What are your thoughts about being a socially conscious artist in this particular moment of political strife in America?

AG: What I’ve really done is to outgrow this moment of political strife in America! We’ve always been in a moment of political strife. The one thing I’ve noticed is we live in a time when people are more free to express themselves individually and less like a group. That was the thing that I thought marked my parents’ generation, the greatest generation — they acted as a team; they put aside being an individual. Now I’ve seen that change to where a person’s personal belief system is more important than any group philosophy. I’ve noted that change and found it disheartening, but I think it’s a natural evolution. I don’t get caught up in the day to day left or right as much as I used to. I still hold true to my core values and if somebody sides with me at one time or another that’s great, and if I’m able to hang out with them and support them I’ll go do it, I don’t care what party they belong to or what their story is. Their individuality and sense of honor and trustworthiness is more important than the temporary condition of thinking one thing.

I’m old enough to have changed my mind many times! I don’t like it when newspapers or others in the media recall what you said 20 years ago, and I don’t think it’s fair! You want to allow people to evolve and change their mind and grow. To keep pointing back to what they said or did … there are times when that is important, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not a general rule with me. I’m a bit more “live and let live” than I used to be.

AF: Have any of your songs changed their meaning to you over the years?

AG: Not really. My core values have not changed — I’m still me and I’m still for the average guy. People can be swindled and people can be fooled. You have to bear with them and help get them through it. It doesn’t matter if they’re left, right, or center, it happens to us all — we all get overrun with the fear of doing nothing. It’s usually an urgent call to do something that catches my attention, and when that happens, I look upon that call with suspicion. I always have and hopefully always will.

AF: Thanks for the interview, Arlo, and also for a famous moment in my family where I thought you were singing about “Coming into Los Angeles/bringing in a couple of geese.” My dad had to explain to me that it was “keys” and what that meant [kilograms of drugs]. I mean, “mister customs man” wouldn’t have been okay with you bringing in any geese!

AG: [Laughs] That song was banned in Boston! And not for that line, but for something else, and for that I am so proud. It’s great to be banned!

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe and DigBoston, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home: Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a 2022 Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by the New York Times.