Jazz Album Review: “Luis Russell — At the Swing Cats Ball”

By Michael Ullman

This collector is happy to have Luis Russell: At the Swing Cats Ball with all its faults.

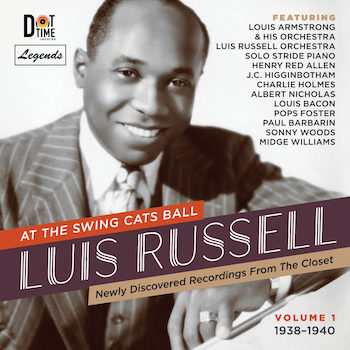

Luis Russell: At the Swing Cats Ball: Newly Discovered Recordings from the Closet: Volume One, 1938-1940 Dot Time Records DT 8022

Born in Panama in 1902, bandleader and pianist Luis Russell died in 1963. Annotator Paul Kahn calls him “the leader of one of the greatest orchestras in the history of jazz,” which seems to me to be a bit of an exaggeration. Russell is mostly remembered as the leader of the big band that accompanied and recorded with Louis Armstrong, and, less consistently, backed another great New Orleans trumpeter, Henry “Red” Allen. (Russell was the arranger and pianist on Red Allen’s 1929 masterpiece, “Biff’fly Blues” and many others.) Russell made his first recordings with cornet player George Mitchell (hear him on Jelly Roll Morton’s 1926 masterpieces), clarinetist Albert Nicholas, and tenor saxophonist Barney Bigard, who would achieve fame with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Between 1926 and 1929, Luis Russell was also the pianist on King Oliver’s recordings. His band was filled with New Orleans players, including the exemplary rhythm section of Paul Barbarin on drums and Pops Foster on bass.

Born in Panama in 1902, bandleader and pianist Luis Russell died in 1963. Annotator Paul Kahn calls him “the leader of one of the greatest orchestras in the history of jazz,” which seems to me to be a bit of an exaggeration. Russell is mostly remembered as the leader of the big band that accompanied and recorded with Louis Armstrong, and, less consistently, backed another great New Orleans trumpeter, Henry “Red” Allen. (Russell was the arranger and pianist on Red Allen’s 1929 masterpiece, “Biff’fly Blues” and many others.) Russell made his first recordings with cornet player George Mitchell (hear him on Jelly Roll Morton’s 1926 masterpieces), clarinetist Albert Nicholas, and tenor saxophonist Barney Bigard, who would achieve fame with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Between 1926 and 1929, Luis Russell was also the pianist on King Oliver’s recordings. His band was filled with New Orleans players, including the exemplary rhythm section of Paul Barbarin on drums and Pops Foster on bass.

By 1929 he was based in New York City and leading a prototypical swing band, one that included the great Red Allen, who was featured on recordings such as “Feelin’ the Spirit” and “Jersey Lightning.” Russell was also accompanying Louis Armstrong. Their first recordings, of “I Ain’t Got Nobody” and “Dallas Blues,” were made on December 10, 1929. After a break, Armstrong and Russell would work together steadily from 1935 to 1943. At the Swing Cats Ball has 11 recordings made of Armstrong on the radio with Luis Russell’s band between 1938 and 1940. It is from out of Russell’s closet, we are told, that the 20 performances on this astonishing new disc were discovered. The glass or shellac records found in that somehow previously untouched closet were made, according to the notes, for Russell’s own consumption: they consist mostly of songs that he did not otherwise record. Presumably Russell wanted to hear them for himself and judge them by himself. Nonetheless, I assume that Armstrong was in charge of his repertoire.

A word about the sound. The source discs were “heavily worn.” “The resulting sound quality reflects these limitations,” we are told. Worse, “In some cases we have only a fragment of the song.” The collection begins with seven numbers recorded at the “new Grand Terrace Café” on the south side of Chicago. First there is a fanfare and then, over a syrupy version of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” an announcer brings on Louis for a few snappy words before the band starts playing something called “Jammin’.” Armstrong takes a warm, but not particularly dramatic (for him) solo, but the piece, and the set, is just as notable for solos by Red Allen, the fine trombone player J.C. Higginbotham, and New Orleans clarinetist Albert Nicholas. Armstrong contributes a high-note solo to bring “Them There Eyes” to a thrilling conclusion. It’s notable how generous “the trumpet king of swing” is to his soloists: he doesn’t dominate as he did in his commercial recordings. The first solo on “Blue Rhythm Fantasy” is by alto Charlie Holmes. It’s an incomplete performance: “Blue Rhythm” fades away as the emcee is still babbling. Armstrong sings the first chorus of “I’ve Got a Heart Full of Rhythm” and then there’s a solo by Albert Nicholas before Armstrong returns on trumpet. “Riffs” is unfortunately split in two. Armstrong introduces “brother Red,” giving another trumpeter the first solo. He then introduces trombonist J.C. Higginbotham, the beginning of whose solo is lost in static. The forgettable “Mister Ghost Goes to Town” is composed of two fragments. In the second surviving part, Armstrong encourages his soloists: “Red Allen will now take charge” he calls out to his rival trumpet player.

What follows are five numbers by the Luis Russell Orchestra without Armstrong, beginning with the hysterical vocal by Sonny Woods on “Ol’ Man River.” Thankfully, he’s followed by Red Allen. To my ears, the highlights of this set are the series of solos “At the Swing Cats Ball,” with its ensemble chorus of boogie-woogie followed by an exuberant solo by Higginbotham and then by Red Allen. That, and Allen’s composition “Algiers Stomp.” The collection continues with two cuts recorded in 1939 and 1940 by Armstrong’s Orchestra, but featuring the vocalist Sonny Woods. Despite the dismal message of the number’s lyrics, Woods sounds like a carnival barker on the medley “Melancholy Lullaby and Lilacs in the Rain.” Armstrong’s short trumpet solo seems to be an afterthought. Finally, there are four examples of Luis Russell’s solo stride piano, which seems to me most notable for the way he speeds up the already up-tempo numbers.

Nonetheless, this collector is happy to have At the Swing Cats Ball, with all its faults. It rounds out our knowledge of Armstrong and of his reputation. Despite the high price of the tickets, his Grand Terrace shows were sold out. Lines of fans waited to get in. Again and again Armstrong is proclaimed to be the “king of the trumpet.” We hear fine contributions from some of the sidemen and occasionally we get to listen to Armstrong cut through the fog of the recorded sound with his bright and vibrant tone and his controlled mastery of any length of solo.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: At the Swing Cats Ball: Newly Discovered Recordings from the Closet: Volume One, Dot Time Records, Louis Armstrong

Michael Ullman’s fine review is greatly appreciated.

Calling Luis Russell’s Orchestra one of the greatest, I took my cue from Brian Rust, described by the NY Times as the father of Jazz Discography, who wrote about Luis Russell in his liner notes to the Parlophone/EMI reissue LP (1967) The Luis Russell Story 1929/30.

“Here, incidentally (speaking of the recording Jersey Lighting), we have a rare glimpse of the leader’s piano work, a fine amalgam of Harlem stride and Jelly Roll Morton ragtime (on Savoy Shout, there are traces of Earl Hines, by the way, but Russell was no flagrant copyist. Had he been, his whole band would surely have lacked the superb individualism that made it one of the greatest in the entire history of jazz).” – Brian Rust

Incidentally, the aforementioned 1967 reissue LP went on to be featured on the cover of the December 1967 issue of the UK magazine Jazz Journal as one of three Jazz Records of The Year alongside Miles Davis and Duke Ellington releases.

Paul Kahn, album producer and author of accompanying booklet