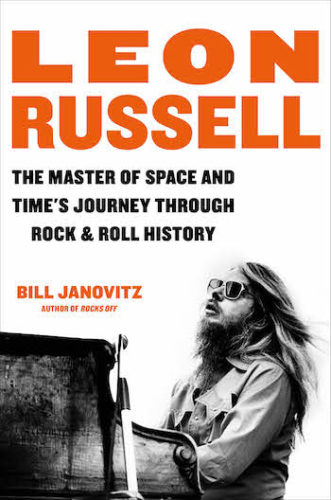

Book Review: “Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History”

By Scott McLennan

Even more impressive than the sheer amount of raw knowledge Bill Janovitz puts on display is the way he expertly elaborates on Leon Russell’s familiar résumé highlights to create a full, three-dimensional portrait of a very complicated artist (and person).

Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History by Bill Janovitz. Hachette Books, 592 pages, $31.

There’s a good chance that Bill Janovitz’s stunning new biography of Leon Russell will take longer than usual for you to finish reading, and that’s not simply because the exhaustive work comes in at 536 pages before another 50 or so pages of acknowledgments, notes, and an index.

There’s a good chance that Bill Janovitz’s stunning new biography of Leon Russell will take longer than usual for you to finish reading, and that’s not simply because the exhaustive work comes in at 536 pages before another 50 or so pages of acknowledgments, notes, and an index.

Rather, Janovitz gives such a detailed account of Russell’s life and work in Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History that, almost without fail, any given chapter will tempt readers to put down the biography for a moment to conduct a few Spotify searches and pull up songs they never knew had any connection to Russell. (Anticipating this diversion, Janovitz has curated a massive playlist on Spotify dedicated to Russell, the songs he contributed to or that he wrote and were performed by other artists).

Even more impressive than the sheer amount of raw knowledge Janovitz puts on display is the way he expertly elaborates on Russell’s familiar resume highlights — the writer of “A Song for You” and “This Masquerade”; architect of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour; collaborator with George Harrison on the Concert for Bangladesh; the late-career comeback guided by Elton John — to create a full, three-dimensional portrait of a very complicated artist (and person).

Janovitz lives in Lexington, Massachusetts, and has written two books about the Rolling Stones. He painstakingly avoids churning out a clean but predictable narrative arc, where a brilliant artist hits the big time, influences a generation of popular music, makes a ton of money, loses a ton of money, fades away from the public eye, and then has a late-in-life career comeback before dying. Instead, Janovitz captures the multifaceted realities of a remarkable life full of as much pain and loss as it was rich with triumph and success. And Janovitz shows how all of it was inevitably intertwined: Russell’s highest highs were scarred with personal trauma — be it a busted romance or falling out with a friend. Similarly, Janovitz examines the work Russell made after his commercial peak in the early ’70s, stuff that was often met with public indifference or critical scorn, and reveals what brilliant moments are buried there.

In addition to having already written successful rock-lit books, Janovitz is a founding member of ’90s alt-rock band Buffalo Tom. He brings an impressive level of expertise to deciphering complex music-business machinations as well as a deep understanding of the information he had access to regarding recording sessions and production notes. Janovitz is a reliable guide through weedy turf; he turns Russell’s career ups and downs into a grand story that will appeal to general readers as well as music fans.

Janovitz also comes at this task as an unabashed fan of Russell’s work as a piano player, ace session musician with credits on hundreds of famous records, bandleader, producer, and songwriter. He lays out Russell’s early career path (over the course of which Oklahoma’s Russell Bridges transforms into L.A.’s Leon Russell) with dramatic aplomb as readers chart Russell’s move from backing Jerry Lee Lewis to working with artists as diverse as Herb Alpert, Gary Lewis, Glen Campbell, the Beach Boys, and Willie Nelson. Finally, Russell explodes into the public view as a wild rock ’n’ roll preacher whose fusion of Southern soul, R&B, blues, and swampy funk would open a whole new vein in American music.

Biographer Bill Janovitz. Photo: Kelley Davidson

Russell died in 2016, at a time when his career was on more of an upswing, but nowhere near the arena-show levels he scaled in the ’70s. (Russell’s final appearances in Boston were typically at the 1,100-seat Wilbur Theatre).

But, while Janovitz is adept at pushing out just how important a role Russell played in the development of popular music, he is equally savvy about just how badly, and how often, Russell undermined himself.

Examining Russell’s drop-off in popularity, starting around 1974, Janovitz concludes, “But he did not putter out, nor did the world simply pass him by; he jerked the car into the ditch.”

Still, despite his psychological waywardness, there is also something to be admired in Russell’s stubborn pursuits, at least when it comes to music. Janovitz writes about Russell’s role in the early use and development of synthesizers and drum machines and examines how he was exploring video as a media for music well before MTV. Artistically, Russell’s willing desire to follow new threads with his work could often lead to something brilliant, such as his swerve into country music when he made the so-called Hank Wilson albums. At times, he could jump into a much murkier direction, such as his collaboration with the Gap Band.

Russell’s best songs — “Delta Lady,” “A Song for You,” “Hummingbird,” “Lady Blue” “Ballad of Mad Dogs and Englishmen,” “Tight Rope,” “Shootout on the Plantation,” “In the Hands of Angels,” “Stranger in a Strange Land,” and “This Masquerade” — were all inspired by his personal life. So too were some of his more career-upending projects, such as the flat-sounding mid-’70s records he made with his then-wife Mary McCreary. (The couple’s inability to sound very good together foreshadowed the marriage’s harsh meltdown.)

Janovitz gives us a deep dive into the life Russell lived off the stage and away from the studio. He follows the Okie kid, beset with physical ailments that would worsen across his lifetime, to California, where the musician embraces the hippie culture, falling in and out of love with women who stay in his life (for better or worse) well past the expiration date of the initial romance. Then it’s back to Tulsa for Russell and his expanding family and business before he decamps to Tennessee and builds a life and career around Nashville.

The tangle of wives and children is central to Russell’s life and work, and Janovitz does his best to bring in as many of those familial voices as he can.

Russell’s expansive story is, at times, overwhelming. The names of musicians, producers, staff members, recording engineers, and hangers-on stack up quickly (Janowitz reports that he conducted more than 137 interviews and was given access to Russell’s unpublished autobiography as well as other business and family documents).

It’s easy to lose track of all the people and places despite Janovitz’s best efforts to provide a few clear through lines to help guide the tale, such as Russell’s decades-long friendship with Willie Nelson; the rise, fall, and ripple effect of Shelter Records, the record label Russell and Denny Cordell formed; or a subplot around the making and long-delayed release of Les Blank’s free-form feature documentary about Russell, A Poem Is a Naked Person.

Janovitz is at his most effective whenever he keeps Russell as the protagonist, which is an accomplishment when you consider who some of the other major players in this story are: Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Tom Petty, and Elton John, to name a few. In this biography, we watch the enigmatic, brilliant, conflicted, and downright weird Russell enter and exit the lives and careers of luminaries who far outshone him in a commercial sense. But he always treated them on his own terms.

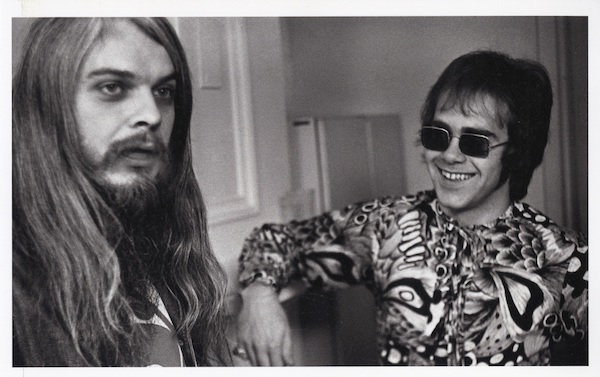

Leon Russell and Elton John. Photo by Don Nix, courtesy of the OKPOP Museum

Russell remained defiantly independent to the end, breaking away from the team that Elton John assembled to engineer Russell’s 2010 comeback with the album The Union and induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame the following year. John was aghast to see just how far down the ladder Russell, whom he considered not only a crucial early influence but also a musician to be treasured, had fallen. As much as Russell is reported to have appreciated all that John did for him, he could not go along with the superstar’s long-term plans about recording with hip outside producers and hitting the promo circuit of talk shows and the like.

John’s manager Johnny Barbis, who was guiding Russell’s career during The Union period, told Janovitz, that Russell amicably split from Team Elton with the quip, “You guys made enough money off of me.” Janovitz, like any rational person would, questions Russell’s bad decisions, which threw his career, family life, and financial security into various states of disarray over the years.

But the biographer makes it crystal clear that Russell is someone to admire, an artist who preferred to take his chances on the tightrope rather than safely travel down familiar roads again and again.

Janovitz will discuss, with author Tom Perrotta, Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History at 7 p.m. tonight at the Harvard Book Store, 1256 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge.

Scott McLennan covered music for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1993 to 2008. He then contributed music reviews and features to the Boston Globe, Providence Journal, Portland Press Herald, and WGBH, as well as to the Arts Fuse. He also operated the NE Metal blog to provide in-depth coverage of the region’s heavy metal scene.

Tagged: Bill Janovitz, Elton John, Hachette Books, Leon Russell, biography

Nice. I’m interested in the book.

Been a fan for lot’s of years, love Leon!!

Look forward to reading the book.