Visual Arts Review: The Trouble with “Symbionts” — and an Unlikely Antidote

By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

Many of the entries in Symbionts do not question scientific worldviews as much as attempt to validate art in a world ruled unquestionably by science.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere at the MIT’s List Visual Arts Center through February 26.

Dare to Know: Prints and Drawings in the Age of Enlightenment at the Harvard Art Museums (closed).

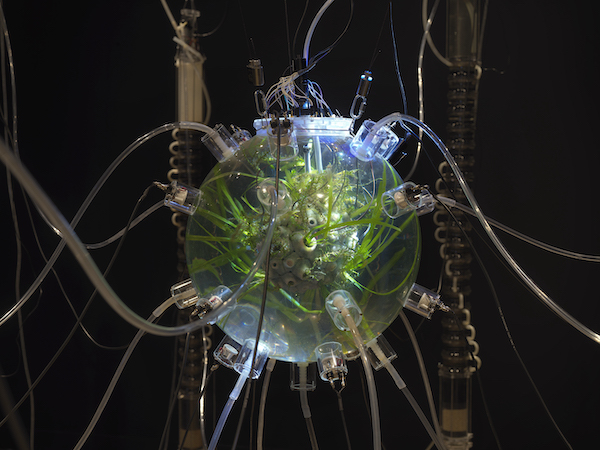

Gilberto Esparza, Plantas autofotosinthéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants], 2013–14 (detail). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

To be a good symbiotic partner requires surrendering to the unknown, according to Donna Haraway’s book Staying with the Trouble (2016), on the library cart at the entrance to the show. Haraway’s text is sprinkled with words and neologistic pairings like “interconnectedness,” “becoming-with,” and “response-ability,” all meant to invoke our intense, entangled relations with the biospheric Other.

“Chthulucene” is Haraway’s coinage for the unprecedented times we live in and the “under-world” we must engage if we want to get through them. Joining forces with other organisms to address our climate misdeeds is the call from beyond. But Haraway’s theory, if intended as a cue for visitors — and readers of the delectable Symbionts catalog — falls short. A true sense of the unknown is somewhat rare in this exhibition. Some of the work is exceptional in bringing us into the world our symbiont partners occupy; other work does more or less the opposite, attempting to render even the most alien system a known set of constraints.

Walking into Gilberto Esparza’s Plantas autofotosinthéticas (2013–14) caused a bit of confusion. Had we turned right when we should have turned left? Are we in an actual laboratory? Esparza’s installation is an impressively detailed hydraulic network of tubes (microbial fuel cells) and flowing wastewater gathered from sites around Boston into a central orb where something is growing — protozoans, crustaceans, aquatic plants. This self-contained ecosystem takes up an entire room. There is even a control panel with dials, switches, and measurement devices, which museum guards are diligent in reminding visitors not to touch. But is this science or art? Or just a spectacle? It certainly isn’t a parody; it lacks the self-awareness.

A more modest installation reflecting on scientific methods, their use and abuse, shares the space in an adjacent room. Crystal Z Campbell’s Portrait of a Woman I and II (2013) and Friends of Friends (Six Degrees of Separation) (2013–14) use bacteria slides typically placed underneath a microscope to peer into “HeLa” cancer cells, extracted without consent from the cervical cancer of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, in 1951. These cells are “immortal.” They continue to divide when most cells would die, an anomaly which has made possible countless medical and scientific breakthroughs. Yet Lacks, and her “gift,” has gone unrecognized. Campbell and collaborators have etched Lacks’ portrait and a portrait of HeLa cells into solid glass cubes atop slender dark pedestals a few feet away from the wall-bound bacteria slides. On the one hand, it is difficult to reconcile the beautiful fuschia stains and bright yellow backdrop of the miniature slides with their painful origin story. But perhaps the tension heightens the horror and poetry of the elegy — a powerful statement on the valuation of Black bodies and a haunting example of biotic partnership based on extraction.

Installation view: Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, 2022. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Other work in the show incorporates actual bacteria and fruiting bodies into portraits of everyday relationships, including Candice Lin’s Memory (Study #2) (2016), Jenna Sutela’s Gut Flora (2022), and Nour Mobarak’s Sphere Studies (2020). Funneling the juices of partners and prospective co-parents, mother and child, and museum staff, these sculptural pieces make remarkable use of organic processes. Lin’s Memory (Study #2), for example, features a plastic bag inside a wiry red ceramic container growing lion’s mane mushrooms. To nurture the mushrooms, gallery attendants must periodically douse them with distilled urine from a nearby dispenser. In Sutela’s framed reliefs, fired mammalian dung forms the faint outline of flowers delivered to the artist on the occasion of the birth of her second child. The sheen across the three blooms is a breast milk derived casein glaze. Last but not least, Mobarak’s colorful Spheres populate the central gallery space like forgotten beach balls, sprouting turkey tail fungus in delicately textured folds.

Around the corner, Anicka Yi’s Living and Dying in the Bacteriacene (2019) wall-mounted aquarium contains freshwater algae waving and weaving its way over a web of 3D-printed honeycombs. The filamentous algae, considered a nuisance in customary aquarium settings and ponds, comes alive and shapeshifts in rich hues of green.

Each of these works invites a microorganism in as opposed to pulling it out or having it eradicated. But rather than appearing on their own, as perhaps they would in some posthuman future that finds the List Center abandoned, each artist sets the terms for how they will grow. We are not shocked by these symbionts, if that was the point. Nor are we particularly moved or feeling-connected. It becomes obvious (particularly upon repeat visits) that their decay, and thriving, depends entirely on us.

Claire Pentecost’s soil-erg (2012), meanwhile, is less engaged with mossy fungi or verdant algae, and more with mundane soil, the very definition of earthy. The two-part installation combines drawings of currency and compressed soil block formations that resemble gold bricks. The monetary connections are intentional: Pentecost asks us to envision an alternative financial system in which ingots of soil are as good as gold. Money would celebrate microorganisms, along with the heroes of science, art, and cultural criticism. Aside from the impressive textural quality of cast dirt, the project is mostly a sentimental, anthropomorphic gesture, the first visitors encounter as they enter the show. The mole and smiley mouse illustrations are more simplistic than animalistic, and the characterization of people on the currency are right out of a textbook for school children.

Some of what’s on view in the first galleries of Symbionts resembles science-for-all-ages, the stuff of exploratoriums or the other MIT Museum. Without the technological grounds or motivation, however, the art ends up caught in a web of its own silliness. Overstated concepts and redundant explanations close off even the most formally sophisticated art in this vein, and partnership appears more a matter of domestication than negotiation with otherness. We are hardly disturbed. Where is the critique? What is at stake, as artists and reviewers alike used to ask of an artwork?

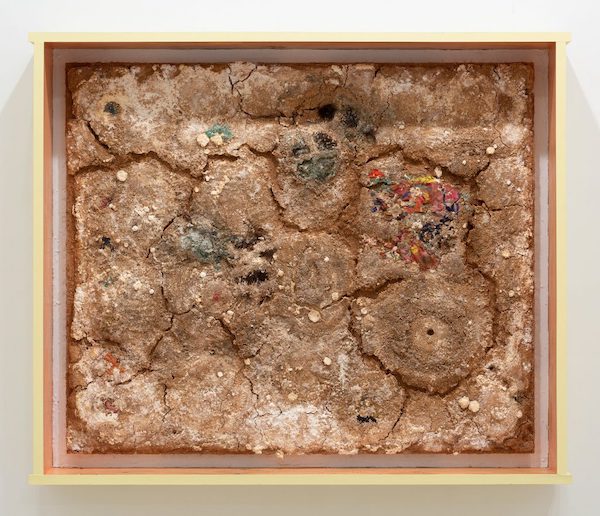

Mobarak’s Reproductive Logistics (2020) incorporates elements of mid-20th century surrealism and art brut, as well as the hair and sperm of former lovers. The painting is embedded in a substrate of hungry mycelium. On top of this it is explained to us that the mens’ contributions are part of a partially destroyed palette for a portrait of the artist herself. While the piece is something to look at, the exegesis muffles the material innovation and wit. We have nothing left to discover for ourselves. Mobarak and the artists mentioned above propose dismantling the barrier between studio and laboratory, doctor’s office and kitchen garden; but what is the result of their experiments? Are we more or less enlightened or enlivened as a result?

Nour Mobarak, Reproductive Logistics, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery. Photo: Stephen Faught.

It is easy to see why this show is hosted by one of the premier scientific institutions on the planet. Many of the entries in Symbionts do not question scientific worldviews as much as attempt to validate art in a world ruled unquestionably by science. The intent is to make the art timely, it seems, by putting it at the service of scientific knowledge — mainstream or otherwise — and to make it part of the scientific “solution” to biospheric problems. When art becomes instrumental in this way, the viewer’s experience is also undervalued, made secondary. However, this is not the only way that art can be engaged with science, and vice versa, as we can see in another show just a few miles down Massachusetts Avenue.

At the Harvard Art Museum until Sunday, Dare to Know: Prints and Drawings in the Age of Enlightenment traces a historical and narrative arc through the European Enlightenment. The show covers the period roughly from 1720 to 1800. We encounter scientific triumphalism at this more traditional exhibition, to be sure, but that perspective is mixed with a candidness about empirical limits, about acknowledging the “real but unknowable,” an idea first made popular during the Enlightenment by the philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Dare to Know contains much that is eerie, even vicious, in its assemblage of drawings and prints of vegetables and the moon from the 18th century. We don’t think twice when we come across images of such things in contemporary media; yet these works take us back to a different time. There is a weirdness built into them and an unnerving quality that feels substantive. Standing before Lunar Planisphere, Hypothetical Oblique Light (1806), viewers lose themselves in one father-daughter pair’s wild, seemingly endless stipple and line engraving of the surface of the moon.

The life drawing and social commentary in the show are no less strange, or extreme. The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751) by William Hogarth is filled with unimaginable horrors, many inflicted on domesticated cats and dogs. While such prints inspired animal welfare reform, the art itself does not prematurely or presumptuously pretend to solve the maddening scenes. Francisco Goya’s Los Chinchillas (The Chinchillas) (1799) depicts a blindfolded woman in donkey ears feeding two apparently helpless men with locks on their ears blocking them from hearing. That these people fail to think for themselves is not lost on viewers then or now.

Nicolas Maréchal’s less well-known but equally empathetic Ursus maritimus (Polar bear) is an undated drawing of the newly observed creature and its experience of two little humans — looking like no two people you’ve ever seen before (except maybe in a drawing by Odilon Redon). They are more like what an artist might imagine we would look like from the perspective of a giant, wet, sweet-faced bear.

Whether staging encounters with more-than-human reality or unprecedented cruelty, Dare to Know lacks the off-putting self-consciousness, even self-righteousness, of Symbionts. The bear’s different perspective, and the myriad monsters in corners of maps throughout Dare to Know recall Haraway’s Chthulucene and remind us of Pimoa cthulhu, the spider she claims as inspiration (along with the Greek word “chthonios,” meaning “of, in, or under the Earth and the seas”). While Haraway disavows any relation between her term and the horror writer H.P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928) — after which this spider, at least, was named — both Chthulucene and Cthulhu attempt to describe what is all too real but hidden from sight. To whatever degree Lovecraft influenced Haraway’s conception, it seems relevant to consider his earlier idea for its emphasis on the unknowable’s difference from humankind; in Lovecraft’s story, Cthulhu was unpronounceable by the human voice.

Nicolas Maréchal, Ursus maritimus (Polar bear), Drawing for an illustration to Ménagerie du Muséum d’histoire naturelle (Menagerie of the Museum of Natural History) by Etienne de Lacépède (Paris: 1801). The Horvitz Collection, Wilmington, Del. © The Horvitz Collection.

At the Harvard show, science seems to need art. The show leads us to consider whether art might serve science better not by mimicking it but by reminding science of its limits. Some of the headlining work in Symbionts seems to forget its power to critique. As it sets out to remake the monetary system or to introduce an element of “play” into wastewater remediation, Symbionts may embrace a “general aesthetic of amensalism,” in which neither art nor science benefits, and art is harmed. In The Return of the Real (1996), critic and art historian Hal Foster identified a “general aesthetic of spectacle” in the reappropriation of images for its own sake. As far as the parallel goes, does art in Symbionts merely reproduce DIY bacteriology? Or reenact didactic methodologies (if not prescriptive analytics) the show purports to challenge? The simulation may be seductive and appear to be “in the know.” But it is an art that largely distracts, whether dealing in mushrooms or “vacuum cleaners in Plexiglas displays,” as Foster encapsulated spectacularly predictable art from the ’80s and ’90s. In contrast, many drawings in Dare to Know attend to the real in their serious-minded pursuit.

In the dark and perfumed recesses of Symbionts there are some examples of contemporary art that echoes Dare to Know, albeit through the use of up-to-date materials and techniques. The ethic here seems entirely different from the one that locates symbiosis in controlled fungal or algae formations. Alan Michelson’s Wolf Nation (2018), for example, uses webcam footage of endangered red wolves from a sanctuary in New York state. Michelson creates an augmented reality by panoramically reshaping the flat video recording of the wolves’ downtime, the long horizontality meant to resemble an indigenous Wampum belt. The pixelated footage, projected with a purple stain (highlighting, perhaps, the surveillance nature of the original footage), portrays just a few, mostly banal minutes in the lives of these captive wolves. Added to this is a wonderfully disembodied, wolfy soundscape composed for the artist by Laura Ortman, which follows patrons throughout the show. The longer we watch, the more the wolves’ autonomy becomes apparent — though we remain stationary observers. We are left confronting the uncanny in a form that is initially, in some way, familiar to us, which is Michelson’s point. A Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Michelson gives us a piece that, far from mimicking a scientific worldview, subtly deconstructs and remakes scientific observational practices, visually, sonically, and physically suggesting a different way of knowing.

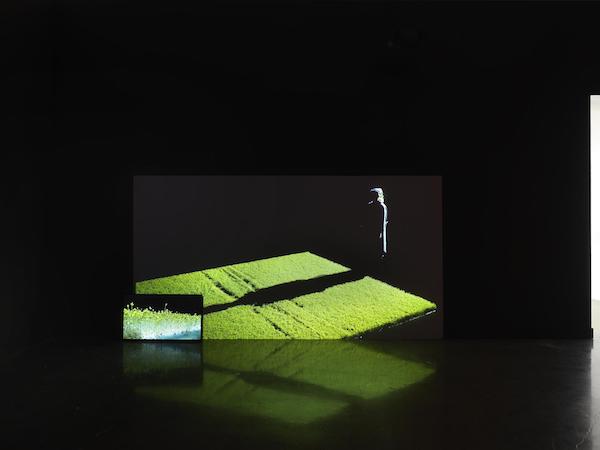

Špela Petrič, Confronting Vegetal Otherness: Skotopoesis, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Michelson’s installation appears in the farthest room of the show across from one bearing a similar, if more pointed message. In a reversal of Basho’s famous haiku — “Sitting quietly, doing nothing, Spring comes, and the grass grows, by itself” — Špela Petrič’s Confronting Vegetal Otherness: Skotopoiesis (2015) features a two-channel visual that ruminates on stillness. The first, a wall-sized projection depicts a woman (the artist herself) dramatically backlit as she stands peering over a bed of germinating cress, casting an ominous shadow. In the corner, a home-sized monitor plays footage zoomed-in on the overcast section of the cress in cross section: from the leggy, light-deprived top shoots all the way down to the roots in the soil.

What Petrič’s time-lapse-less installation does for us is similar to Michelson’s, if more cheekily knowing and thus slightly irritating. It asks us to stay with this patch of vegetation for just a little while, without presuming, as the artist says, to know “what the experience is like” to watch the herbaceous greens in front of us. We can’t really see them sprout in real-time, nor can we sense ourselves shrinking slightly as we stand, more or less immobile. We can feel something, and catch the artist twitch or wobble. The result is a kind of shock at the unknowable when we least expect it.

Pierre Huyghe, Spider, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Pierre Huyghe’s Spider (2014) achieves the most success in this respect. Characteristic of the shock artist, this is a simple but astonishing piece. Huyghe procures twenty “daddy long legs” spiders from a local biological supply. He instructs the museum staff to situate them in a corner of the gallery space. The museum staff also puts text about the piece on the museum wall. When we enter the gallery, we see no spiders, at least not at first. Then we see what could be one low on the wall, in the corner. Is it real? We blow on it. It moves. We then look up and see several other spiders hovering ominously over us.

Spider’s prankster antics may be off-putting to some, but this example of conceptual art is also the most fully realized in the show, not only because of how it draws on our curiosity. This is a visceral demonstration of symbionts, which can be familiar but remain mysterious, often unsettling, and capable of their own agency without one another’s prior consultation or input.

Pamela Rosenkranz, She Has No Mouth, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

In a fitting finale, Pamela Rosenkranz’s installation She Has No Mouth (2017) leads a “parallel life” alongside Huyghe’s spiders. The minimalist, mauve mandala bathed in pink LED light is a turn on. No joke. It’s got Calvin Klein Obsession for Men wafting through it. In this last room of the exhibition — across the hall from the rest of the List galleries — there is a lot going on. We were alternately aroused, scared, surprised, repulsed, and remorseful. Investigating the work entertained and edified. An artist can rely on wall text, if they are as restrained, thorough, and savvy a storyteller as Rosenkranz. (It turns out that the single-celled protozoan Toxoplasma gondii and the African civet cat from which the synthetic pheromone Civetone derives, have been working together, and employing us as intermediary hosts, for quite some time.) She Has No Mouth is about recent scientific discoveries, natural history, art and industry the way “a mouse is about a house,” to quote the late poet Charles Simic on the meaning of poetry.

Michelson, Petrič, Huyghe, and Rosenkranz do not instruct us on how to be “good” or “better” biotic partners. They do not doubt our knowledge of symbiosis but rather bring the biospheric equivalent of a readymade into the gallery space where they can explore it with us. Borrowing from the lab in playful, original, and artful ways, reconstituting the wild nature of all a lab contains, these later pieces stand in contrast to the science experiment installations, utopian documentary projects, and cultivated painting and sculpture that open the show.

The best work in Symbionts does something unexpected, seizes us unaware, like a magic trick or dream. It brings us into the present. Not for the greater good, necessarily, but in greater awareness of our own subject position in relation to the subject of the world—wolf, spider, cress, civet life. Who knows where such awareness could take us.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.

Tagged: List Visual Arts Center, MIT List Visual Arts Center, symbiont