Book Review: “On The Marble Cliffs” — History as Dreamscape

By Thomas Filbin

Maintaining liberty in the face of totalitarian fantasy calls for vigilance. Ernst Jünger’s cautionary tale may be more resonant now than when it was first published.

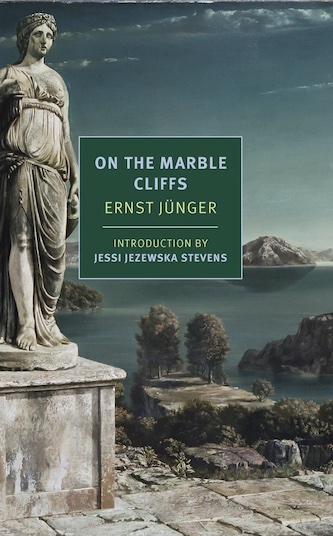

On The Marble Cliffs by Ernst Jünger. Translated from the German by Tess Lewis, introduction by Jessi Jezewska Stevens, afterword by Maurice Blanchot. New York Review of Books, 125pp, $14.95.

Ernst Jünger, both as a man and as a writer, required a large canvas upon which to work. Born in 1895, he joined the French Foreign Legion and then the German army at the beginning of World War One. A much-decorated officer, he rejoined the army during World War Two but spent most of his time in Paris where he fraternized with French intellectuals and writers. His first book, 1920’s Storm of Steel, was a powerfully graphic (and critically acclaimed) memoir of his experiences in battle on the Western Front. He was both a German patriot and an anti-Nazi, a dangerous combination his literary stature neutered. (Jünger continued to write up to his death at age 102.) First published in 1939, On The Marble Cliffs is a short but poignant novel that succeeds as an allegory on the rise of fascism. The book does not hammer home its anti-authoritarian message: it requires thoughtful and patient reading. The narrative is not plot driven; it is a dreamscape that constructs an alternative world, a riposte to the quotidian. It is not so much writing that tells a story as one that places us in a counter-life.

Ernst Jünger, both as a man and as a writer, required a large canvas upon which to work. Born in 1895, he joined the French Foreign Legion and then the German army at the beginning of World War One. A much-decorated officer, he rejoined the army during World War Two but spent most of his time in Paris where he fraternized with French intellectuals and writers. His first book, 1920’s Storm of Steel, was a powerfully graphic (and critically acclaimed) memoir of his experiences in battle on the Western Front. He was both a German patriot and an anti-Nazi, a dangerous combination his literary stature neutered. (Jünger continued to write up to his death at age 102.) First published in 1939, On The Marble Cliffs is a short but poignant novel that succeeds as an allegory on the rise of fascism. The book does not hammer home its anti-authoritarian message: it requires thoughtful and patient reading. The narrative is not plot driven; it is a dreamscape that constructs an alternative world, a riposte to the quotidian. It is not so much writing that tells a story as one that places us in a counter-life.

Two brothers live in an ancient house and occupy themselves with botanical studies, investigations that seemingly disconnect them from the impending invasion led by a cruel despot called The Head Forester. We know little about the protagonists beyond this, which is part of Jünger’s literary strategy: they are not psychological creatures that develop but figures in a symbolic picture that depicts a seismic societal shift. In this experimental excursion, Jünger wanted to eschew traditional categories and invent his own – it is a credit to that spirit of innovation that this book still disarms after 80 years.

For example, Jünger takes considerable liberties with geography, suggesting at one point that Campagna and Mauretania are on the same continent. Suspension of disbelief might be an obstacle for some readers, but their patience will be rewarded once it will become clear that exact locations are not important. The book is really about becoming alienated from language, contracting an acute awareness of the limitations of words. Early on, the narrator calmly observes that he was seeing things “with unclouded eyes for the first time… and experienced the most painful sensation of words becoming detached from things….” He adds that “the word is both king and conjurer.”

This apparently placid world of study and love of nature is torn asunder once the military (and linguistic) aggression of the Head Forester begins. Jünger clearly depicts how a dictator puts a playbook into action, spreading disease into healthy tissue. “He spread fear in small doses, which he then gradually increased… In this he was like an evil doctor who inflicts an ailment in order to subject the patient to his intended surgery.”

On the one hand, the fable is about how innocence is crushed, in the mode of Voltaire’s Candide. But a more apt comparison would be that On The Marble Cliff partakes of the self-absorbed decadence found in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ Against Nature: objects, impressions, and experiences are valued more than ordinary life events. To be is to absorb and reflect upon our experiences. The novel ends with a huge conflagration, a Wagnerian Gotterdammerung, which leaves the two brothers alive but charged with reinventing themselves in a new world.

Among the reasons to appreciate Jünger’s book today is his beautiful prose. “Then evening descended with a green shimmer as if from verdant grottos. The garlands of honeysuckle hanging down from above gave off a rich scent and the colorful hawk moths rose, whirring, to their horned yellow flowers.” On The Marble Cliffs is very much under the spell of modernism: it presents a world self-consciously built out of words. There are irritating digressions — too much is said about hounds, for hounds — but they can be seen as metaphors for the continual threat of violence. And Jünger injects some satiric wit. He writes about one character: “Like every crude theoretician, he fed on those sciences of the moment…” I could not help but think of people who believe that to understand what’s on the internet is to understand everything.

Ernst Jünger in 1921.

The translator, Tess Lewis, is a much-honored practitioner of a difficult craft. She is admirably alert to this unusual novel’s nuanced shades of meaning, figures of speech, and implicit as well as explicit symbolism.

Jünger’s book had obvious significance in 1939, at a time when the globe was about to be engulfed in wars that pitted fascism against democracy. For decades, many believed that the age of despotism was long past. But the current rise of populist demagogues and autocrats, promising a better world — if we only abandon notions of rights, individual liberties, and respect for minorities — proves otherwise. History appears to be surreal: maintaining liberty in the face of totalitarian fantasy calls for vigilance. Jünger’s cautionary tale may be more resonant now than when it was first published.

Thomas Filbin is a book critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Sunday Globe, and Hudson Review.