Film Review: Rediscovered, Paolo Di Paolo — A Photographer Who Abandoned Photography

By David D’Arcy

You can forgive director Bruce Weber for gushing in admiration about photographer Paolo Di Paolo’s uncovered legacy. There’s plenty to gush about.

The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo Di Paolo, directed by Bruce Weber. At the moment the film has no theatrical distributor. Check local listings for screenings.

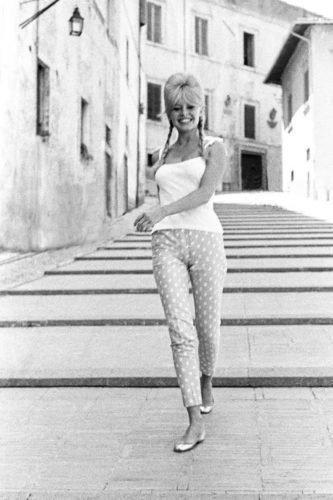

Brigitte Bardot. Photo: Archive Paolo Di Paolo

The photographer Paolo Di Paolo, now 97, has been called, by some, the Henri Cartier-Bresson of Italy – that is, by those who are familiar with his work. You can’t help noticing the similarities between Di Paolo and the witty French master of haphazard configurations of light and darkness, who saw endless odd juxtapositions in everyday situations.

Cartier-Bresson worked when surrealism was active in France and shared some of the surrealist sensibility although his was in a gentler vein — it was magic realism before that term was used and overused, the kind of magic that can be found in realism if you’re there at the right moment.

Di Paolo found it — whether it was black-clad priests, in Italy’s Carabinieri (national police), or in the landscapes where solemn ancient ruins were forced to accommodate noisy cars and other unruly machines of the modern world.

His pictures are more charming than jarring. Was he a clever observer of things around him, or just lucky to be where he was when he snapped the shutter? It was a lot of both.

In the inventive and warmhearted documentary The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo Di Paolo, the photographer/filmmaker Bruce Weber introduces Di Paolo to a public that didn’t know him or his work before, which is just about everybody. Weber confesses that he has loved everything Italian since he was a boy outside Pittsburgh, so Di Paolo was a good fit for him as a subject. In the ’50s and ’60s, Di Paolo photographed what Italy was or was transforming into, at the time. The title “Il Mio Viaggio in Italia” was already taken by Martin Scorsese in his overview of Italian cinema. But it wouldn’t have been out of place here as a term for Di Paolo. Once more pictures in his vast archive are seen and catalogued, that title is likely to fit even better.

Yet, after the late ’60s, few aside from some dedicated collectors and aging figures from the days of la dolce vita knew his name or his pictures — not even his children knew of his fame. Starting in the late ’60s, Di Paolo worked for decades as “art director” of the Carabinieri, the national police force, and helped his son launch an antique car business.

Given that abrupt career shift — the deliberate abandonment of a craft that he practiced so publicly and so well — you can argue whether finding Di Paolo today rates as a discovery or a rediscovery. Either way, his pictures are stunning.

Around five years ago, Weber was struck by photographs he saw at a gallery in Rome, pictures of everything from farm workers huddling in the midday shade to Anna Magnani sleeping in the sun next to her dog.

Weber tracked down Di Paolo, then in his early 90s. A trickle of images became a trove, once Di Paolo brought out the pictures he had saved since his time as a working photographer — about 250,000 images, all told.

The selection of those photos we see in the film are treasures indeed. Di Paolo had an eye for place, for character, for portraiture, and for the collision, inescapable in postwar Italy, between the past and the present.

You can forgive Weber for gushing in admiration about about the photographer’s uncovered legacy. There’s plenty to gush about.

But, beyond the pictures, there is the film’s appealingly avuncular central character, Paolo Di Paolo. At 97 he has a vivid memory and an eagerness to tell stories — virtues enviable in a man of his charm who has wonderful pictures as illustrations. Befitting his age, he also has some valuable wisdom to share.

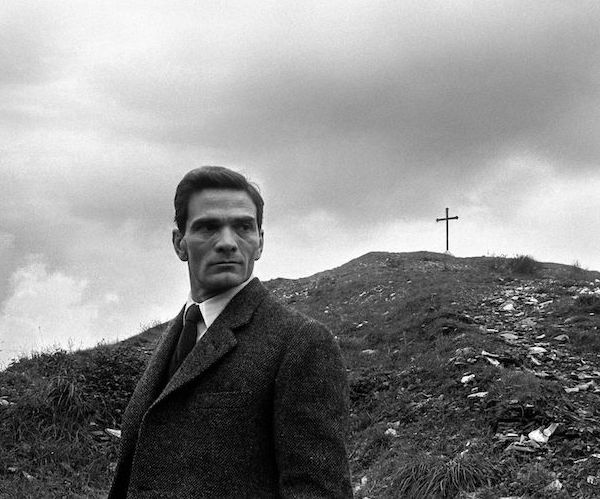

Pier Paolo Pasolini. Photo: Archive Paolo Di Paolo

We learn that Di Paolo left home for Rome as a young man in 1949. I’ll let him tell those who see the film how he survived a childhood illness that everyone thought would kill him — a miracle, whether it’s true or not. He tells Weber that he was unprepared for the world outside the quiet impoverished town of Larino in the Molise region. Today, depopulated villages are offering families $27,000 to move there.

“Twenty years of fascism had created a cloud around all of us, especially young people,” he recalls. “We couldn’t see anything beyond this cloud. I can say that we weren’t unhappy during fascism. To be unhappy, you have to know what happiness is.”

Di Paolo’s camera observed Italy struggling to be get back on its feet, often framed by his revealing pictures of friends like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Anna Magnani.

He tells Weber, “They often ask me, ‘How did you create these intimate moments with these people?’ … If you don’t get excited, you don’t create beautiful things.”

As Di Paolo revisits his years as a photographer, Weber presents a choreography of still images and moving pictures from the period, shifting between scenes of public performances and private life. Since so many of the interviews that Weber shot with Di Paolo and his daughter Sylvia (a guide to her father’s work, once she knew of it) are in black and white, the images form a graceful ensemble of people that takes us through people and places in the past.

Discouraging nostalgia from the rapturous filmmaker Weber, Di Paolo, the man who photographed as many beautiful people as anyone, issues a warning. “Great satisfaction with one’s work is the exclusive right of dilettantes.” So it really wasn’t as easy or as much fun as it looks? And Di Paolo insists to Weber that there was and is life after photography, decades of it. Weber isn’t entirely convinced.

But Di Paolo has a point. Art, or the craft of art, provides a living for a fraction of the people who practice it. And even those who make art successfully often made a living before or after that success doing something else. Ask any waiter.

The fact is, Di Paolo, who stopped photographing when television killed the magazine business in Italy and paparazzi drove out serious photographers, didn’t just decide to leave the business. The business left him.

Weber quotes Cartier-Bresson, a master at capturing the eternal moment, on expecting too much from the medium. “Life is very fluid. Sometimes the picture disappears and there’s nothing you can do. You can’t tell the person, ‘Oh, please smile again, or do that.’ Life is once forever.”

True enough, yet Di Paolo’s years of picture-making are being reborn — as the man moves toward the age of 98. To say that the pictures feel alive today understates how exhilarating they can be.

Don’t expect any systematic analysis or critical evaluation in Weber’s affectionate, appreciative documentary. As thousands more of Di Paolo’s pictures become available, there will be plenty of time for a closer look.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.