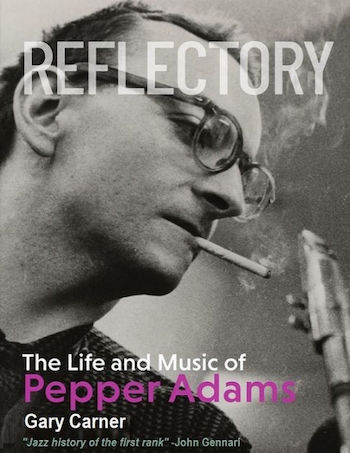

Book Review: “Reflectory: The Life and Music of Pepper Adams” — An Enigmatic Master

By Steve Provizer

It’s hard to imagine anyone producing a more complete and authoritative biography of baritone sax player Pepper Adams.

Gary Carner’s biography Reflectory: The Life and Music of Pepper Adams is a definitive look at the gigs, recordings, and movements of this baritone saxophone master. Portraying the inner man is a lot tougher. Adams’s relationships with others ran from the harmonious and the off-putting to the discreditable. Throughout, his emotional life remained inscrutable. Carner paints a credible picture, but this study would have been stronger had the author’s fondness for his subject been tempered by his responsibility to give the reader a more evenhanded portrait of this enigmatic musician.

Gary Carner’s biography Reflectory: The Life and Music of Pepper Adams is a definitive look at the gigs, recordings, and movements of this baritone saxophone master. Portraying the inner man is a lot tougher. Adams’s relationships with others ran from the harmonious and the off-putting to the discreditable. Throughout, his emotional life remained inscrutable. Carner paints a credible picture, but this study would have been stronger had the author’s fondness for his subject been tempered by his responsibility to give the reader a more evenhanded portrait of this enigmatic musician.

This is a weighty tome, which was predictable given that Carner spent 37 years researching and preparing the biography. He has done a thorough job of accumulating information about Adams and detailing his major musical influences. About releasing the study in eBook form, the author says: “By cutting out the middleman, the book remains affordable, its scope doesn’t need to be reconsidered, and photographs, audio samples, and music examples aren’t a constraint.” This was a good decision, if for no other reason than the hyperlinks in the text lead to almost all the songs Carner refers to in the text. Click on a link and the list of relevant tunes comes up, arranged by chapter. His book makes the case that Pepper Adams is woefully underappreciated — and the best way he can press his argument is by letting us listen.

Much of the book deals with Adams’s Detroit connection; understandable, given that he came to musical maturity there and continued to have tight relationships with musicians in that city his entire life. One learns much about the scene, which made a big impact in New York once many Detroiters moved there in the mid-to-late ’50s. But, as he writes about the Detroit scene, Carner tends to tiptoe around difficult elements, in much the same way he does when dealing with Adams. Detroit musicians are described as being both supportive and combative; elders generously pass on information but do not abide incompetence. Of course, any “scene” is bound to be complex and not easily characterized. But the author tends to flatten out the contradictions, particularly those that lead to the negative. He is committed to being uplifting, which is also how he limns Adams’s thorny personality.

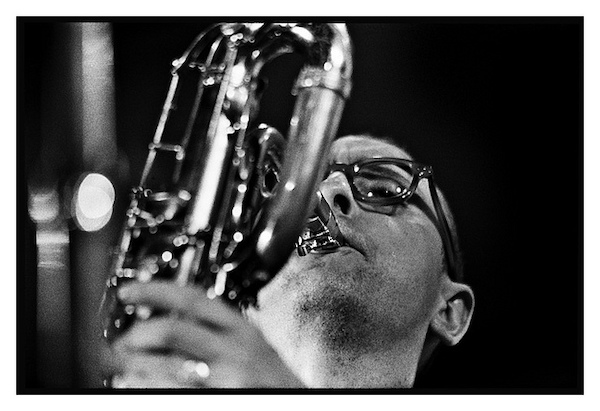

Perhaps Carner believes that, if he leans too hard on the difficult aspects of Adams’s personality, it would undermine the book’s principle argument: that Adams was the most influential baritone sax player since the bop revolution, and that he elevated the status of the baritone sax more than any other individual in jazz, but has not been given appropriate credit for his achievement.

Adams had few important predecessors on the horn, chiefly Ellington stalwart Harry Carney, then Leo Parker in the ’40s, followed by Serge Chaloff, Cecil Payne, and Gerry Mulligan. A case can be made that Adams became the dominant baritone soloist in the late ’50s, but to say that he elevated the status of the horn more than Mulligan is debatable. Mulligan’s fame, for better or worse, far exceeded that of Adams.

Pepper Adams — the biography claims Adams was the most influential baritone sax player since the bop revolution.

The author draws a strong line in the sand between Mulligan’s lighter, “whiter” sound and Adams’s, although there was some overlap in their approach to ballads. Mulligan was more about interplay with others — Chet Baker and Stan Getz, for example. Adams was a balls-out bopper; his most singular self is heard in up-tempo, multichorus jaunts, where he was able to negotiate the big horn as if it were an alto sax. When you look at their respective pedigrees, it’s clear that Adams’s skills were forged in a Black environment and Mulligan’s in a white one. Mulligan’s apprenticeship (as much arranger as baritone player) was in white bands led by Elliot Lawrence, Gene Krupa, and Claude Thornhill. Following that, he worked with Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool Band. Adams, on the other hand, was most closely associated with the Detroit school of musicians, which included Barry Harris, and Thad, Hank, and Elvin Jones. He had an early stint in Stan Kenton’s orchestra, but most of his career was spent performing with Black groups. As Carner appropriately points out, “Adams was the only white musician who recorded for Blue Note throughout the late fifties, sixties, and early seventies.” In the long run, the more intense, “Black” sound of Adams seems to have triumphed. It has been adopted by a new generation of baritone players, like Gary Smulyan, Hamiett Bluett, and Ronnie Cuber.

I don’t fault Carner for being fond of his subject, but his lack of distance undermines the persuasiveness of his cause. Carner writes, “Even though Adams did not finish his studies at Wayne, wasn’t formally trained as an educator, and was insecure about his pedagogical approach, he was nevertheless in the forefront of jazz education in North America.” The actual extent of Adams’s teaching was that, at a certain point, he started doing a couple of clinics a year. Carner’s praise is hyperbolic.

The author struggles, as Adams did, with figuring out why his reknown (and income) remained inadequate for most of his life. (Adams died at 55 of lung cancer — he had been a very heavy smoker.) One reason put forth is that low-pitched instruments like the baritone sax are simply not that appealing to a wide range of listeners. Yes, but other explanations Carner proffers ring truer: Adams did little to take charge of his own career. He seemed to be content to be a sideman. He refused to double on another instrument, which meant he got little studio work. Also, he could be acerbic when it would have served him to be tactful; he ended up alienating people who could have helped his career. Finally, he was not a particularly physically attractive man. Rather than compensating for that with better clothes or a snappier presentation, Adams doubled down on looking unkempt and sallow.

As is typical of many jazz musicians, Adams left almost no paper trail, apart from some letters. Adams’s solitary, emotionally detached, and often sardonic personality made Carner’s task considerably more difficult. His chief pathway into Adams’s inner life are the 250 interviews he conducted. But these, while instructive, supply circumstantial, often contradictory evidence. Carner habitually puts his thumb on the positive end of the scale. That aside, it’s hard to imagine anyone producing a more complete and authoritative biography of Adams. Of course, the quality of the music stands by itself. Listening to his magnificent baritone sax playing while reading Reflectory adds immeasurably to the experience.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Gary Carner, Gerry Mulligan, Pepper-Adams, baritone sax, be-bop

This review is so well written, but chastises Gary Carner a bit over a steadfast awe for Pepper Adams. Thumb on the scales, or words to that effect. Pepper’s scales and wails have had me in in awe – or more specifically – laughing with joy for a long time. Joy Road has led me here. I have ordered Reflectory.

A reader kindly pointed out that Adams was NOT the only white musician who recorded for Blue Note throughout the late fifties, sixties, and early seventies. There was J.R. Monterose.

I Love Pepper Adams never heard a record he did that sounded uninspired ON to my ears!. i am going to purchase the biography and just enjoy the fact that someone has taken time to write it all down for us….give us an eye and ear into this great talent a Jazz giant of the Baritone Saxophone…

For any Lovers of the Baritone Saxophone there is a little known Baritone Player Tate Houston that Recorded with Jazz Trombone player Curtis Fuller on Blue Note records label in 1957-8 the LP is called Bone & Bari.

Jazz lives.

I’m continually amazed at the lack of respect given to giants such as Pepper Adams. I’ve not read the book, but having read this unkind review (unattractive man, etc.) my stomach turns. Pepper Adams was likely, the greatest modern jazz baritone saxophonist, period! Similar disrespect has been given to Stan Getz in various writings. Give it a rest guys. Enough is enough!

Lack of respect? “His book makes the case that Pepper Adams is woefully underappreciated — and the best way he can press his argument is by letting us listen.” “Of course, the quality of the music stands by itself. Listening to his magnificent baritone sax playing while reading Reflectory adds immeasurably to the experience.”

If you’d really read the review, you’d know I was trying to get to WHY he was not given his due.