Book Review: “Charlie’s Good Tonight” — A Rare Gift of Groove

By Tim Jackson

Charlie’s Good Tonight does a fine job of illuminating Charlie Watts’s personality and paying homage to the drummer’s admirable legacy.

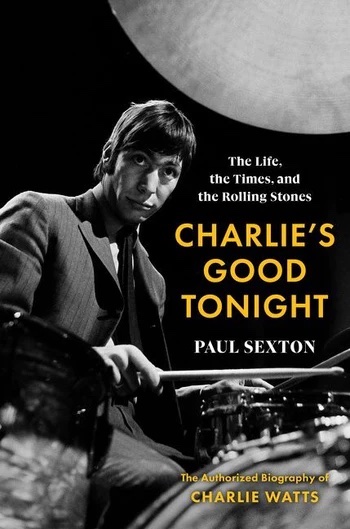

Charlie’s Good Tonight: The Life, the Times, and the Rolling Stones, The Authorized Biography of Charlie Watts by Paul Sexton. 368 pages, $27.99.

The world has spent decades watching Charlie Watts on his small, perfectly tuned drum kit, the rhythmic backbone for the world’s most enduring rock band. His was the metronomic backbeat that anchored hundreds of Rolling Stones songs, dozens of which were hits. Throughout his career, Watts always seemed to sport a grin that sat somewhere between contented and bored. What was behind that ambiguous grin? After multiple books on the Stones and on Mick Jagger, bassist Bill Wyman’s memoir, I Stand Alone, and Keith Richards’s wild autobiography, A Life, the drummer finally gets his own biography in Paul Sexton’s Charlie’s Good Tonight.

The world has spent decades watching Charlie Watts on his small, perfectly tuned drum kit, the rhythmic backbone for the world’s most enduring rock band. His was the metronomic backbeat that anchored hundreds of Rolling Stones songs, dozens of which were hits. Throughout his career, Watts always seemed to sport a grin that sat somewhere between contented and bored. What was behind that ambiguous grin? After multiple books on the Stones and on Mick Jagger, bassist Bill Wyman’s memoir, I Stand Alone, and Keith Richards’s wild autobiography, A Life, the drummer finally gets his own biography in Paul Sexton’s Charlie’s Good Tonight.

That Cheshire cat grin hid an aristocratic sensibility that sustained an unruffled personality, a disciplined ego that resisted the excesses and vanities shared by many icons of pop music. Watts’s story, as told in the book, lacks the customary tales of drugs, groupies, and hedonistic indulgences that are part and parcel of rock and roll celebrity. Watts was a gentleman in an ungentle business. His consistency and moderation — in music and life — earned him the admiration of his peers and high praise from his unrulier band mates. Watts generally kept himself out of the public eye, but Sexton, a music writer, producer for BBC Radio 2, and author of Prince – Treasury: A Portrait of the Artist, interviewed the drummer a dozen times before his passing. This authorized biography pulls off an adroit balancing act, serving up a view of Watts’s private life while delineating his legacy as one the most notable drummers of the last century.

Drummers are often either the clowns or the peacemakers for their respective outfits. The percussionists among the legendary bands who invaded America from England in the ’60s were either maniacal or steadfast. The Who’s Keith Moon and Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham — who brought brilliantly fresh approaches to the instrument — were destroyed by alcoholism, legendary road antics, and general self-abuse by their early 30s. The loopy Ginger Baker, a respected jazz player, peer, and friend of Charlie Watts, managed to hang on until age 80 (see the fine documentary Beware Mr. Baker).

Conversely, Ringo Starr’s diplomacy and quiet creativity provided a solid foundation for the singular creativity of the Beatles. Then there is the civilized Watts. He wore bespoke Savile Row suits (a 2006 Vanity Fair Magazine elected him to the International Best Dressed Hall of Fame) and was a gifted graphic artist who sketched the interiors of every hotel room he stayed in while touring. A jazz aficionado, he was ambivalent about rock and roll and bemused by the celebrity that came with it. He quietly married Shirley Ann Shepherd in 1964 against the advice of his band members, who insisted that getting hitched could compromise his rock star image. The pair stayed together for 57 years, breeding Arabian horses. “We’ve had horses ever since we were married but I’ve never ridden. I do have the most wonderful outfits to go riding in: britches and 3 pairs of boots. I have some lovely old carriages,” Watts says.

Watts, along with other musicians of his generation, was raised amid the economic ravages of postwar Britain. Like Jagger and Richards, he had early ambitions to be a graphic artist. Rock and roll offered him a far more romantic and lucrative future. In the early ’60s he was already in demand because of his dependability, treasured for how he could play with the directness, swing, and simplicity of the traditional American blues and R & B drummers. He particularly admired the older generation of jazz players, such as Chico Hamilton, Joe Jones, and Art Blakey. His recognition that rock and roll, too, should have a kind of swing comes from his deep affection for early jazz. “He was playing very much like the black drummers playing with Sam and Dave and the Motown stuff,” comments Keith Richards.

The fluid ease of his drumming, a nuanced ebb and flow that wafted between the straightness of rock and the swing of jazz, became increasingly rare in our age of programmable drum machines, heavy metal bombast, or fusion rock’s pyrotechnics. Those approaches have their place in music, but Watts’s drumming was exemplary because it remained resolutely grounded, steady, and instinctive. He was gifted with the kind of feel exemplified by Earl Palmer, a lesser-known drummer on many early rock records. Talking about Palmer’s approach, Squeeze musician Jools Holland says it was “almost swinging when they’re straight and straight when they’re swinging. It’s a minuscule thing of feel, and it’s a hard thing to define, but when you got it, you’ve got the world, and not many people have it. Charlie had that. It was one of the foremost qualities of his playing, a gift of groove that all drummers aspire to.”

Charlie Watts in 1965. Photo: Wiki

As they were looking for a drummer, the Stones sensed that Watts would provide one of the keys to the band’s success. The iconoclastic Ginger Baker suggested Watts to Brian Jones, insisting that “your drummer is absolutely dire. Why don’t you get Charlie Watts?” In his own biography, Richards remembered thinking, “God, we’d love that Charlie Watts if we could afford him because we all thought he was a God-given drummer.” But Watts agreed only if they could provide enough solid gigs on the books to pay him. They agreed that they would; in addition, they would help him lug his drums on and off the tube.

Sexton chronicles how Watts slowly acclimated himself to playing rock and roll. He didn’t like Elvis much, had a low opinion of rock and roll in general, and actively disliked “flower power.” Nevertheless, he applied himself to listening to early rock and blues records, particularly those of Jimmy Reed. Eventually he began to develop an appreciation for the form. He came up with an unembellished style that remained constant over the decades, a solidly metronomic foundation on which Keith Richards’s guitar riffs could build tracks unencumbered by complexity or grandstanding drum parts. As for live performance, Richards explains, “It’s just one big circle really. But the one who mustn’t make a mistake was old Charlie at the back. If he got confused and gave us the wrong beat, we’d be up a gum tree!” He continues, “With the fantastic ‘whoosh’ of sound coming from the audience, he has to lip read what Mick is singing most of the time. Charlie takes his cue from Mick; Brian, Bill and I take it from Charlie and Mick takes it from the lot of us.”

Watts was fastidious. Sexton recalls the time a worker sat to play on Charlie’s drums while they were waiting for the band to show up at a recording session. When he discovered this, Watts didn’t explode in anger (as Baker was known to do), but “commented on how good they were.” One time an engineer tweaked a tension rod on his snare drum half a turn. It didn’t change the tuning, but Watts noticed how the response of the head had changed. “It didn’t bounce back quite the way he would expect it to dash and he knew immediately.” Both Wyman and Watts had OCD, a trait that made them a crack rhythm section. “I am fastidious,” Watts told Esquire in 1998, “but not as fastidious as Bill Wyman.” The latter reflected, “I don’t know why but we became this great rhythm section that everybody admired and we were always on time, always ready, always available, always sober, and they can always rely on us…. If you ever see any of the videos you can see me and Charlie at the back laughing at them while they are doing all that crazy stuff they used to do jumping off beds and going through walls and things.”

Charlie’s granddaughter Charlotte says, “I always believed that he had OCD. It was really entertaining.” Sexton includes several examples of Watt’s obsession with behavioral routines and neatness, especially his wardrobe. When Watts realized that he might have to wear a T-shirt in performance, he had his custom made with pleats. “He was never untidy. You hang your coat up, you never put it on a chair,” recalls his sister Linda. He even had a special coat rack to put his jacket on before he sat down on the drum throne for shows. “On the road Charlie had two suitcases and that was it.… To watch Charlie pack was like watching a Buddhist ceremony,” says Richards.

Charlie Watts on drums. Photo: Wiki Common

Watts’s bespoke suits were, of course, custom made, as were his shoes. He would take long walks to break in a pair of new shoes. Sexton recalls, “He felt it was the customer’s own responsibility to break a new pair in. [Charlie] said ‘Most aristocracy who could afford to have shoes made would have the gardener or butler wear the shoes first to break them in.’ Charlie didn’t agree with that particular tradition.”

Watts considered what he did for the Stones a job, and he approached the task with seriousness and grace. He was proud of his work and of his influence, but was without vanity. When asked, “you must have done a great deal of hanging around in 25 years with the Stones?” his effortless reply was “worked for five years, and 20 years hanging around.” Sexton writes that Charlie was nonplussed by hero worship, almost to the point of annoyance. “As Charlie grew older … adoration of him among scores of thousands of stadium fans grew ever more palpable. He simply didn’t know where to put such adulation other than to sit at his drum stool looking like he was praying for it to finish.”

Charlie Watts died at a London hospital on August 24, 2021, with his family around him. He was 80. Charlie’s Good Tonight does a fine job of illuminating his personality and paying homage to his admirable legacy.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Charlie Watts, Charlie’s Good Tonight, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, The Rolling Stones

Thank you so much, great review. I am anxiously awaiting my copy of the book which I have been told is coming from Santa Claus. I do think that you miss used the word nonplussed. Cheers, Charles