Book Review: “The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World” — Forever Out of Reach

By Peter Walsh

Paul Fisher’s back-and-forth tease about John Singer Sargent’s sexuality starts out as intriguing, then becomes distracting, and finally irritating as the biographer never quite closes in on his targets.

This biography is thoroughly researched, carefully plotted, and, for the most part, soundly based on fact and not assumptions. John Singer Sargent’s remarkable life and career is traced with energy and enthusiasm.

The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World by Paul Fisher. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 496 pages.

One of the most successful and best-known painters of the 19th century, John Singer Sargent had a virtuosity that astonished everyone, from his teachers and fellow students in Paris to the art establishment and his friends Whistler and Monet. At the peak of his career, he earned vast sums creating flashy images of millionaires and aristocrats and their families. Yet, even then, doubts began to creep in. Sargent painted only glittering surfaces, charged disillusioned admirers. He had sold out his talents for money and fame. He was old fashioned, out of date, and out of touch with the truly advanced art of his time.

Sargent’s memorial service, in 1925, filled London’s Westminster Abbey with friends, patrons, and admirers. Memorial exhibitions followed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Royal Academy in London. After that, things went more or less quiet for several decades. Modern art had long since moved on.

About half a century later, things began to turn again. There were small exhibitions of drawings and watercolors, mostly private works, that struck a chord. Then came large and hugely popular retrospectives in the 1990s.

Not only was Sargent’s reputation as a leading Anglo-American artist restored, but the scholars and general public who flocked to his shows noticed something else: Sargent was sexy. In a post-Freudian, post-sexual revolutionary world, nearly everything Sargent made seemed filled with a kind of urgent but languorous eroticism. Scholarly studies took note, especially art historian and curator Trevor Fairbrother, in his 1981 article “A Private Album: John Singer Sargent’s Drawings of Male Nude Models,” and his 2000 study John Singer Sargent The Sensualist.

Sargent was a lifelong bachelor who, although he was rumored once or twice to be close to proposing, never had a verified romantic relationship with a woman. On the other hand, he maintained close friendships with many male artists and with his male models, some of whom he worked with for years and one who became a long-term live-in valet. His male nudes were prolific and, to contemporary eyes, strikingly erotic. Could Sargent have been gay? Fairbrother said yes, but the hard evidence is pretty thin.

Sargent’s biographers are not lacking primary source material. Throughout his career, Sargent kept a wide circle of friends, which included prominent artists, like Whistler and Monet, and well-known writers, including Oscar Wilde, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Henry James, a close friend and mentor after Sargent relocated to London from Paris in the 1880s. There were also hundreds of patrons and professional associates, many of whom were his correspondents and some, including three of his male models, who described him in memoirs and reminiscences. This material has been sorted through again and again. In all of the written documentation, there is hardly a hint of a secret life aside from a couple of hearsay rumors, nonspecific and unsubstantiated. The most explicit of these, an alleged conversational remark from the portraitist Jacque-Emile Blanche, related in a 1927 letter from Bloomsbury art critic Clive Bell, claimed that Sargent was “notorious in Paris and in Venice positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger.”

Fairbrother cites this allegation several times, but Sargent’s most recent biographer, Paul Fisher, says that “these reports have rightly been questioned.” In a footnote, Fisher goes on to explain that “Blanche’s comment was heard secondhand, and from a man who was a well-known liar.”

Fisher, a professor of American Studies at Wellesley College, does not precisely frame his new biography, The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World, as a work in “queer studies” or “queer theory,” the emerging academic field, pioneered by the late literary scholar and critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. But he uses the word throughout his book, and focuses intently on Sargent’s sexual identity, constantly searching for the definitive clue that will prove his case. Spoiler alert: he never finds it. He explores plenty of hints and suggestions, but as historian Teodoro A. Agoncillo warns, “no document, no history.”

John Singer Sargent, Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs. Wertheimer, 1901.

Fisher does make use of the verified sources to great effect. His biography is thoroughly researched, carefully plotted, and, for the most part, soundly based on fact and not assumptions. He traces Sargent’s remarkable life and career with energy and enthusiasm.

Fisher’s narrative is particularly vivid and detailed on Sargent’s early upbringing and education, which, to say the least, were unconventional. The artist’s parents, originally from Philadelphia, are often described as “wealthy.” They were not. His father, Fitzwilliam Sargent, once a promising Philadelphia surgeon and medical author, was from a formerly prosperous Massachusetts family that had gone bankrupt. John Singer’s mother, Mary Newbold Singer Sargent, came to inherit just enough to support the family, if they were careful, and stayed in Europe, where the dollar went further than back at home.

The young family’s first trip to Europe, as was common at the time for well-off Americans, was for Mrs. Sargent’s health, following the death, by illness, of their two-year-old daughter. Except for visits, none of them ever returned to the States. The Sargents lived more like a troupe of itinerant actors than their fellow truly wealthy expatriates, bedding down in hotels and furnished lodgings, shifting camp every few months with the seasons, and apparently owning little beyond their clothes, personal effects, a few decorations, and the steamer trunks and portmanteaus they hauled them around in.

John was born in Florence in 1856, several years into his family’s European life and a year before his sister Emily. The pattern of his life seems to have been set in early childhood: the rootless, nomadic lifestyle; loyalty to his parents’ birthplace while continuing to live abroad (he first visited the United States at age 20); a close, central relationship to his parents and his two surviving siblings, Emily and Violet.

Fisher describes John’s mother, Mary, despite her claimed need for constant travel for her “health,” as indomitably “brisk and energetic” with an “indefatigable love of culture.” Her fascinations, not shared by her physician husband, included “art, history, music, architecture, and other refined tastes.” She led the family on long, circular migrations from Switzerland to Nice; then Paris, Munch, Salzburg, Milan, Genoa, and Nice again. During winter stays in Rome, she kept a “white-capped chef” and gave small dinner parties, “with ices,” for expat friends.

On expeditions with her children around the Eternal City, Mary encountered artists from the international art community — American, English, German, French, Danish. She was also, from childhood, an artist herself and carried sketchbooks on her travels where she recorded her impressions. Only a couple of late examples survive. One art historian has rated her artistic accomplishments as “rank amateur.”

Apart from some brief tutoring in Dresden and classes in Florence, John Sargent had no real education. His family’s constant relocations made it impossible to enroll in local schools for any length of time. Boarding school was the usual expat solution, but his parents were either unwilling or unable to manage the tuition, nor did they send him to live with relatives back in Philadelphia. The family’s idea of home schooling included regular trips to churches, gardens, ruins, and museums, then a growth industry in Europe, and expeditions around the countryside. Like his mother, young John was constantly sketching.

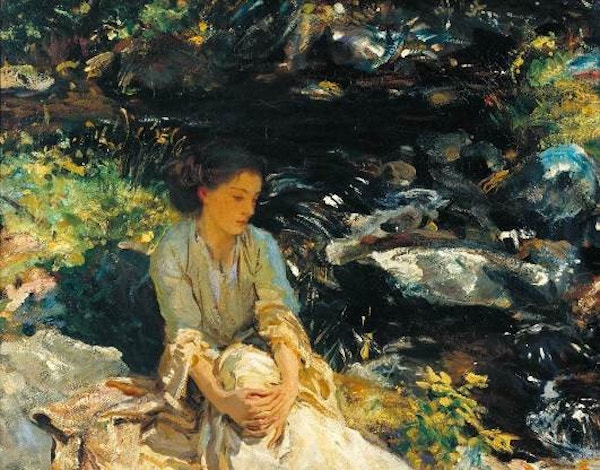

John Singer Sargent, The Black Brook, 1908.

Largely self-taught as an artist, Sargent soon showed a talent so prodigious that his parents, somewhat reluctantly, began to consider more formal training. After a couple of false starts, he joined the Paris atelier of the prominent portraitist Carolus-Duran (Charles August Emile Durand), whose most successful pupils were British and American. The teenage Sargent’s astonishing skills soon earned him the respect and admiration of the entire studio. He became the first of Carolus-Duran’s students to pass the entrance exam for the official and prestigious École des Beaux Arts, where the prominent academic artists and architects all trained.

Success began when Sargent was barely out of his teens. In 1877, he placed second in the École’s concours, won a Third Class Medal for “ornamental drawing,” and had a work accepted for the Paris Salon, the standard route for establishing a reputation and a professional career. In following years, he was shown at the first Society of American Artists exhibition in New York, worked on major commissions with Carolus-Duran, exhibited again at the Paris Salon, where he received an Honorable Mention and later a Second Class Medal, and met the prominent Irish-American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and the architect Stanford White. Eventually he won all the medals the Salon allowed. He began to receive portrait commissions and, while still in his 20s, completed some of his most famous and critically acclaimed paintings, including El Jaleo (now at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston), The Daughters of Edward D. Boit (now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Dr. Pozzi at Home (later exhibited at the Royal Academy at Rome).

John Singer Sargent, Nonchaloir, or Repose, 1911.

Sargent’s breathtaking style — which evoked a vivid, gently breathing reality with a few dashing and seemingly offhand flourishes of oil paint, watercolor, or charcoal — was fixed during these years and did not alter much until he adopted a drier, less virtuoso technique for his late mural commissions. He is sometimes called an Impressionist, but, though he was a friend of Monet, he didn’t really fit the Impressionist mold, loose and accommodating as that was. His approach owed too much to the earlier generation of French Realists and to his studies of Old Masters like Hals and, especially, Velázquez. The stereotypical Impressionist painting, especially as produced by Americans of the next generation, was mostly about capturing the momentary effects of bright sunlight flickering over outdoor surfaces. Instead, Sargent reveals, within his sensuous brush work, the luxurious texture of the clothing and the solid flesh of his sitters, who often emerge from dark, muffled interiors.

Sargent never participated in the French Impressionists’ anti-establishment exhibitions and gestures, nor did he join in the left-wing politics of some of their members. His public career, which included membership in the Royal Academy and other establishment organizations, along with exhibitions at formal salons and at the most prestigious galleries, stayed firmly within the conventional professional boundaries of his time, artistic and social. Shy and taciturn, he had, by all accounts, impeccable manners and an air of unassailable respectability. By his late teens, Fisher relates, he was also, “like his mother florid and dark-haired, amiable, and lively in looks and laughs.” But every successful, fashionable artist was expected to poke at boundaries from time to time, even if without actually breaking them.

John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gaudreau), 1884. This image is of the “reworked” version, made after the scandal, that removed the slipped down strap.

Sargent earned most of his substantial income from society portraits — a type of semi-official art work, privately commissioned but often publicly exhibited, that flattered the reputations of both the sitter and the artist. The trick was to make viewers, at a great house or public exhibition, stop and stare without thinking the artist had gone too far. For the most part, Sargent managed the trick with aplomb; some observers demurred, but most of his audience responded with a shiver of delight.

The notorious exception was Madame X (Madame Pierre Gaudreau). Exhibited at the Salon of 1884, the work created a firestorm of critical reaction. After trying out many different poses, Sargent had chosen to paint his Louisiana-born subject, a well-known and fashionable if slightly less than respectable Paris socialite — described as “that peacock woman” by one of Sargent’s close friends — in a severe black evening gown, her head in profile, against a dark background, with the left jeweled strap of her dress slipped down her shoulder, in “insolent elegance,” Fisher says. At the Salon, the piece created a huge uproar: it was said that cries of Detestable! Boring! Bizarre! Monstrous! filled the gallery where it was displayed. Some critics praised the work, but many others heaped insults on the canvas. “Never have we seen a like decline in an artist who had seemed to to give nothing but hopes,” proclaimed the influential Jules Comte. The painting is now recognized as a masterpiece of the moody, semi-decadent, emerging symbolist aesthetic, the one moment that Sargent was probably most in pitch with the art of his own time.

The uproar seemed to be little more that the latest in a long series of flamboyant “outrages” about edgy or progressive art — from the flaps about Manet’s Olympia and Déjeuner sur l’herbe and the other Impressionists to the Wild Beasts of the Salon d’Automne of 1905 — that periodically entertained the Parisian public (Paris periodicals regularly published amusing caricatures of the most notorious works, as they did of Madame X). Most artists braved such storms without much of a quiver and ultimately benefited from the succès de scandale. Sargent, only 28 at the time of the Madame X scandal, was mortified. He briefly considered giving up his career as a painter and later relocated to London, where he eventually took over Whistler’s old studio on Tite Street in artistic Chelsea, and went on to enjoy much greater acclaim and financial success. Despite the hurt to his much-cultivated respectability, Sargent’s reputation was never really in danger.

This imagined tightrope between respectability and potential scandal runs throughout the rest of Fisher’s biography. He notes an apparent contradiction between Sargent’s lucrative portraits of the rich and powerful with his many images of Italian back streets, Spanish working-class cafes, and exotic locales in North Africa and the Middle East. Fisher never seems to miss a queer association if he can find one. In Venice, Sargent draws athletic gondoliers. In North Africa, he fixes on handsome male Bedouins. Many of his most evocative drawings and watercolors are studies of young, well-built male nudes. Some of the popular tourist haunts Sargent visits — Venice, Capri, and Broadway, the picturesque Cotswolds village and Victorian artists’ colony — Fisher points out, were also frequented by bands of homosexuals.

John Singer Sargent, 1903.

Fisher is too responsible a scholar to push these associations too far. Just before he seems about to proclaim victory in his pursuit of Sargent’s sexuality, he pulls back his troops. In describing Sargent’s Broadway friends and sometime hosts, artist-writer Francis (“Frank”) Davis Millet and his musician wife, Elizabeth (“Lily”), expatriates from Fitzwilliam Sargent’s home state of Massachusetts, Fisher says Frank “may have confided” to Sargent the story of a romantic and sexual affair, a few years before, with the American writer Charles Warren Stoddard. But “then again, he might have kept completely mum.” When Sargent visits Capri, Fisher paints a vivid picture of the queer community there, only later admitting his sources come from years later.

Of Sargent’s many male friends and associates, Fisher concentrates on three who may — or may not — have been sexual partners. All three modeled for the artist frequently. One was the handsome young Anglo-Belgian artist Albert Milbank, who later took his birth father’s name and became Albert de Belleroche. Sargent used Belleroche as a model, Fisher says, more than 80 times. Some of these images have been described as “erotically charged,” and Belleroche has sometimes been described as Sargent’s “presumed lover.” Yet, Fisher concludes, “we don’t know if this was fully a love affair.”

In 1892, Sargent met Nicola d’Inverno, a 19-year-old Italian immigrant to East London and a sometime boxer. Nicola posed for Sargent for years and joined his household as his valet, traveling with him across Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Canadian Rockies until 1918, when d’Inverno, then 45, was involved in a brawl at Sargent’s Boston hotel, the Vendome on Commonwealth Avenue, and had to be dismissed as part of a settlement with the hotel’s management.

Two years earlier, Sargent had met, at the Vendome, a third young man who would become an important model — a 26-year-old African American from North Carolina who was working at the hotel as a bellman and elevator operator. Thomas E. McKeller had a pleasant manner, a handsome face, and an impressive physique. He became an important resource for the large Boston-area mural projects that preoccupied Sargent after he gave up painting portraits. Sargent sketched McKeller repeatedly and used his nude body in the completed murals, although always transformed into a white god or hero. McKeller, with his own features and skin tone, also appeared in nude oil studies Sargent made, apparently for himself.

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882.

Both McKeller, who later found better-paying work at the post office, and d’Inverno left behind recollections of their work with the famous artist. Nicola published his in a Boston newspaper the year after Sargent’s death. Titled “The REAL John Singer Sargent,” it revealed the shocking secrets that Sargent was a freethinker and said “damn” a lot. Neither of these accounts, nor any of the male or female models who sat for Sargent, mentioned anything in writing that could be considered sexual harassment, even by the relatively Puritanical standards of today.

Fisher’s back-and-forth tease about Sargent’s sexuality starts out as intriguing, then becomes distracting, and finally irritating as the biographer never quite closes in on his targets. The approach can distort when Fisher focuses on unconfirmed assumptions and contemporary notions about same-sex relationships rather than on the aesthetic or professional influences of Sargent’s many and varied male friends. Navigating Sargent’s world, Fisher is careful to label all the trees. But he doesn’t seem to realize that the entire forest was cut down decades ago. Victorian attitudes toward sex — prudery and respectability on the surface with everything and anything going on in the down low — have become completely alien to 21st-century conceptions. It takes an enormous effort of the imagination, apparently more than Fisher can muster, to reconstruct them. Whatever sexual landscape Sargent inhabited, it is forever out of reach.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: American Painting, John Singer Sargent, Painting, Paul Fisher, homosexuality, peter-Walsh

I love that quote…”even by the relatively Puritanical standards of today…” This present age thinks it is so advanced, but so many are using the tropes of the past to win their arguments, discredit others and to get their way.