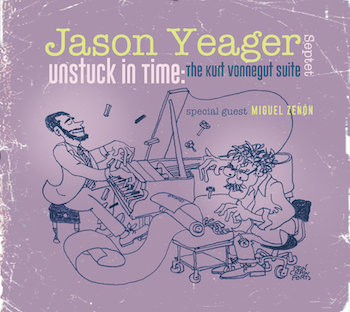

Jazz Album Review: Pianist Jason Yeager’s “Unstuck in Time: The Kurt Vonnegut Suite” — So It Goes

By Michael Ullman

The advantage to listening to the recorded Unstuck in Time: The Kurt Vonnegut Suite is that on disc Jason Yeager writes beautifully for septet: the textures he evokes in his arrangements are curiously varied and invariably moving.

Jason Yeager, Unstuck in Time: The Kurt Vonnegut Suite (Sunnyside)

The Jason Yeager Quartet. Live at The Amazing Things Art Center, Framingham, on October 28.

Near the end of his quartet performance in Framingham, pianist and composer Jason Yeager said he felt that he had “come full circle” this night on Hollis Street in Framingham. Indeed, the concert seemed like a family affair. Peter Yeager, Jason’s dad, was the emcee; Jason attended Milton Academy: the first set was by the Milton Academy jazz band, led by bassist Bob Sinicrope, who was one of Jason’s first teacher;, and the first number was a duet on Sam Rivers’s Beatrice played by Yeager and Sinicrope. When Sinicrope announced that he had just become a grandfather and pointed out the other set of grandparents in the audience, his gesture didn’t seem out of place. Jason’s new project is his disc based on his love of the novels of Kurt Vonnegut. His surprise guest was Kurt’s son, Mark Vonnegut, a pediatrician who describes himself as a memoirist and who is clearly a part-time tenor saxophonist. Vonnegut’s solo on “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” was halting, but he made some satisfying grunts and groans on Jason Yeager’s “Blues for Billy Pilgrim.” After Vonnegut’s unexpected appearance, it was not entirely surprising to learn that a Vonnegut and a Yeager (great-grandfather) were once partners in the architectural firm Vonnegut, Wright, and Yeager, in Terre Haute, Indiana. On this night everything was all somehow tied together.

Near the end of his quartet performance in Framingham, pianist and composer Jason Yeager said he felt that he had “come full circle” this night on Hollis Street in Framingham. Indeed, the concert seemed like a family affair. Peter Yeager, Jason’s dad, was the emcee; Jason attended Milton Academy: the first set was by the Milton Academy jazz band, led by bassist Bob Sinicrope, who was one of Jason’s first teacher;, and the first number was a duet on Sam Rivers’s Beatrice played by Yeager and Sinicrope. When Sinicrope announced that he had just become a grandfather and pointed out the other set of grandparents in the audience, his gesture didn’t seem out of place. Jason’s new project is his disc based on his love of the novels of Kurt Vonnegut. His surprise guest was Kurt’s son, Mark Vonnegut, a pediatrician who describes himself as a memoirist and who is clearly a part-time tenor saxophonist. Vonnegut’s solo on “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” was halting, but he made some satisfying grunts and groans on Jason Yeager’s “Blues for Billy Pilgrim.” After Vonnegut’s unexpected appearance, it was not entirely surprising to learn that a Vonnegut and a Yeager (great-grandfather) were once partners in the architectural firm Vonnegut, Wright, and Yeager, in Terre Haute, Indiana. On this night everything was all somehow tied together.

Jason usefully noted his various Vonnegut inspirations at the ATAC, where he played with his quartet: Mark Zaleski, saxophones and clarinet, Fernando Huergo, bass, and Jay Sawyer on drums. He described the dismal dramatic context for “Unk’s Fate.” The character is a Martian living in a totalitarian world where the inhabitants are kept in line by the playing of a march with the rhythm (Yeager sang it) that goes with the phrase, “rented a tent, a tent, a tent.” Imagine that on a snare drum. Both live and on disc, drummer Sawyer plays this hypnotic (at least to Martians) rhythm. In Framingham, Yeager then briefly took over this rhythm before soloing in his vigorous, sometimes virtuosic style. He started with swift, single note lines. Here, as elsewhere, when he became excited he pounded out two-handed chords that reminded this listener of Brubeck. In Framingham, Zaleski entered with a weird wail on alto saxophone, as if expressing the inner anguish of the drum-controlled creatures. Throughout, Zaleski was a wit as well as a brightly accomplished saxophonist; his agile lines sounded alternately playful and intense on “Blues for Billy Pilgrim,” a highlight of the live set. He shone on clarinet in the “Ballad for Old Salo.” Salo, we were told, is a Tralfamadorian, a one-eyed, two-foot-tall creature abandoned on one of Saturn’s moon. The creature’s further tragedy is that he is rejected when he tries to befriend a human. The mournful solos took place over Yeager’s bell-like repetitive pattern, a lovely, original-sounding version of mournfulness, its melody rising and falling gently in waves. Before playing “Kilgore’s Creed,” Yeager had us chant a creed three times: “You were sick, but now you’re well again, and there’s work to do.” For the pianist, Vonnegut is an inspiration in more ways than one. The piece seems founded on a fast, compulsively repeated rhythm. It sounds like the circus, but maybe that’s what’s needed to get us working again.

Pianist Jason Yeager. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The advantage to listening to the recorded Unstuck in Time: The Kurt Vonnegut Suite is that on disc Yeager writes beautifully for septet: the textures he evokes in his arrangements are curiously varied and invariably moving. When he wants depth, he includes a bass clarinet and flugelhorn. Yuhan Su’s vibraphone peeks through the proceedings. You can’t help but appreciate how the arrangement constantly keeps the sound in flux. On disc, “Ballad for Old Salo” begins with bell-like playing by the piano and vibes. Then trombonist Fahie introduces the melody, beginning with a low, inarticulate smear. His part is followed by clarinet and bass clarinet. There is a gradual crescendo as group members improvise together with the piano prominent. The rich background on “Blue Fairy Godmother” is peaceful in spirit but disturbed by the dissonances of Yeager’s arrangement, which has sudden crescendos as well as floating ensemble passages. “Nancy’s Revenge” has bass clarinetist Patrick Laslie soloing over Yeager’s improvised accompaniment and long tones from the brass, a mini-choir which includes trombonist Mike Fahie.

A bonus on the album is the presence, on “Bokonon” and “Unk’s Fate,” of the great alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon. For the first minute and a half of “Bokonon,” Zenon and drummer Sawyer play a swiftly moving duet. Yeager solos, and then the band takes up the quick angular melody as an ensemble before splitting into choirs on this boppish number. Live, Yeager ended with “Bokonon.” In the notes to Unstuck in Time, he quotes Bokonon’s holy books, which begin: “All of the true things I am about to tell you are shameless lies.” Perhaps Yeager appreciates the holy man’s candor.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.