Arts Commentary: Arts Criticism — Stuck in the Bunker

By Bill Marx

Arts critics are not expected to take the cultural temperature; they are there to reinforce the assumption that the business of the arts in America is … business.

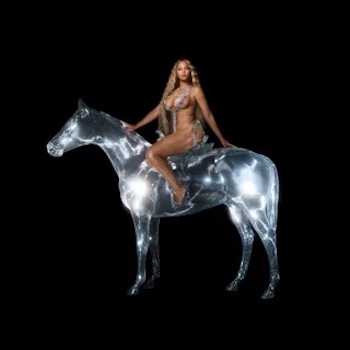

The cover art for Beyoncé’s Renaissance.

“Beyoncé’s Renaissance Shocks Some Life Into a Culture Gone Inert,” pants the headline for Carrie Battan’s New Yorker review of the recently released album. I agree wholeheartedly with the critic that much of our culture is moribund. But why has it gotten this way? Beyoncé’s chutzpah offers a partial answer: “It’s a bold choice and a rejection of commercial interests in the streaming-music era, which has ushered in a protracted dissolution of genre barriers. In theory, the shift to streaming should have enabled innovation; instead, it has helped squash distinct points of view, and nudged many artists in the maudlin direction of easy listening.” True enough. Those who want a more detailed analysis should turn to a series of articles by Ted Gioia in his substack column. He explains — via charts, stats, and buying patterns — how the homogenizing power of technology and economics is driving the dominance of old songs, concluding that “the whole creative culture is losing its ability to innovate.” Visual arts critic Harold Rosenberg celebrated the “shock of the new.” We are now dealing with its slow extinction.

I would like to look at the throttling of the new from another direction. Arts criticism, which used to nurture the innovative, is on life support. Independence of judgment and expertise are in short supply. When it comes to political matters, the chatter never stops. But the mainstream media (online and off-) have pretty well kicked arts critics to the curb. The model appears to be cable TV news — reviewers are only brought in to sound off on a “hot” cultural controversy. Most the time, among those still in their jobs, the task is to come up with “recommendations.” Negativity is banished for the sake of “supporting” the arts and assuring readers and viewers that all is well, the culture is hunky dory. Or they stick to the task at hand: this movie good, this one bad. Critics are not expected to take the culture’s temperature, to diagnose its condition; they are there to reinforce the assumption that the business of the arts in America is … business. The Disneyfication of Broadway never became a cause célèbre for the critics at the NYTimes and other publications — reviewers were happy to see that the seats were filled, albeit via mediocre fare.

This was not always the case. Decades ago, when editors and critics took criticism seriously, reviewers were encouraged to weigh in on where the arts were headed. They issued warnings as well as pats on the back. They saw that one of their tasks was to nurture what they deemed to be challenging new works — welcoming innovation was one way critics contributed to a healthy culture. Reviewers made new works palatable through calming nerves by explaining what they were about — and why they were needed. For example, at the turn of the century New York Sun visual arts critic Henry McBride told readers, sans condescension, why they should not freak out that the flowers in Georgia OKeeffe’s paintings resemble vaginas.

Now, reduced to the boxed-in role of consumer guide, mainstream critics anxiously hold onto their positions, content to fire off a few adjectives, pro and con (mostly the former). Suggesting where our culture is going wrong — and how it might be made right — calls for dissent from the current orthodoxy. Of course, challenges like that will anger the institutional powers — the philanthropic, academic, and media honchos — that drive the industrial arts complex. Isn’t it alarming that the upcoming seasons of our major regional troupes, the American Repertory Theater and the Huntington Theatre Company, are filled with Broadway fare, recycled hits, and imports from London’s West End? Don’t expect to read complaints about the lack of originality in the compliant critical posts from our media syndicate — the Boston Globe and NPR outlets. These reviewers are all for homogenization — they typify it.

I am not the only one who makes the connection between puerile arts criticism and a bland arts scene. Here are a couple of paragraphs from a July 2022 piece by Robert L. Pela, a writer for Phoenix Magazine

The how and why of this is, by now, old news: Fewer people of any age are engaging with print media, so advertisers are spending less on print. As publishers cut page counts and trim staffs, arts coverage and critics are typically the first to go. Even The New York Times’ vaunted arts section has jettisoned talent, “quietly [ending] its coverage of restaurants, art galleries, theaters and other commercial and nonprofit businesses” in pursuit of nonlocal readership, according to a 2016 Deadline article.

The few professional culture and art critics who remain in the Valley must now compete with amateur bloggers and influencers, a new breed of anti-critic with wee writing chops and often scant knowledge of the subject they’re commenting on. Restaurant owners often pay food influencers to visit and enthuse about specific entrées, while theater companies have taken to asking for online “reviews” from audience members.

A respondent with whom I shared this article saw the problem this way: “It’s part and parcel of our utterly failed educational system, the effect of technology and social media on our attention spans, our either/or thinking and our apparently complete inability to connect the dots between subject matter, issues, policies, and underlying values and principles.” Yes, arts criticism has cordoned itself off from bothersome “values and principles.” Technology, via the tyranny of the algorithm, is filling the vacuum. Rather than being encouraged to cast a wide net, consumers are led by the nose by Spotify, Amazon, etc. — if you liked that you will like this, which means you will like this and this and this. This endless loop of predictability is engineered to be thought-free.

Maya Lin, Black Sea (Bodies of Water series), 2006. Baltic birch plywood. © Maya Lin Studio, courtesy of Pace Gallery. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate

But I would like to circle back to the fate of the new by suggesting that reviewers (apparently) are not living in the world the rest of us inhabit. They can’t “connect the dots” because they are exiled in bunkers — partly built by editorial expediency and commercial interests — that value complacency and safety. The precariousness of democracy, the strengthening of native fascist sympathies, the concentration of corporate power, the denigration of science, the widening gulf between the haves and have-nots, the horrific fallout of climate breakdown: why aren’t these realities reflected in what they write about the arts? Aside from an admirable emphasis on diversity, our critics are adrift in a hermetically sealed wonderland, reviewing each performance, film, or book as a standalone event, usually in a value-free context. Where are the demands for plays that fight for democracy and castigate those sympathetic to tyranny? Assaults on the despotism of the algorithm? Calls for the arts to go on a war footing to deal with climate chaos? Manifestos demanding the “Greening of the Arts”? Apparently, polite, high-toned critical circles are uneasy with indulging in alarmist “extremism.” Better to put your head down and crank out feel-good reviews. Radical cries on the margins are bulldozed by the demand that business return to normal after COVID. Pulitzer prize-winning visual arts critic Jerry Saltz’s latest book is titled Art Is Life. Bosh — water is life, and huge chunks of the globe are running dangerously dry, including the western part of the United States.

What does this have to do with the fear of innovation in the arts? “We have to find true sentences,” said poet Ingeborg Bachmann in a 1955 interview explaining why contemporary poetry needed to be so complicated, “which correspond to the condition of our conscience and to this changed world.” The world Americans have learned to market so well is changing, including the nature of our understanding of nature. Isabelle Stengers, in her book In Catastrophic Times, aptly writes that “we are no longer dealing (only) with a wild and threatening nature, nor with a fragile nature to be protected, nor a nature to be mercilessly exploited. The case is new.” The arts in America, on every level, will have to grapple with this transformed reality (if we remain a democracy).

Understandably, there is fear of what might be lost, particularly among the powerful who are invested in today’s economic arrangements. That fear of change is no doubt hobbling our arts critics as well. But the fact is “true sentences” need to be written by critics that hold the feet of the arts to the fire. Demands for art that focus on the climate emergency, such as Maya Lin’s brilliant Mappings exhibition, recently on display at the Smith College Museum of Art. Connections should be made between some significant dots: the megabanks and organizations who are funding the arts are also giving money to a fossil fuel industry that is helping to destroy the planet.

And I have yet to read any speculation about what American culture would look like under an authoritarian setup. Note to Saltz: art was very much alive in fascist Italy. The Arts Fuse’s Ralph Locke just sent in a review of a world premiere recording of a once widely performed Italian opera from 1932. Mussolini was already reshaping Italy into a fascist state by that point, well ahead of Germany. Will Disney, Netflix, Broadway, Penguin Random House, Amazon, etc., keep cranking out the same product as democracy dies? And, if they do, will our arts critics ever protest?

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

I have had a couple of readers who wanted me to clarify my major point in the column. Here goes. World War II influenced the arts and criticism, as did the Vietnam War. Artists and critics has no choice but to reflect in their work the traumatic changes in the world around them — even by attempting to resist them the agonizing circumstances were indirectly acknowledged. We now have the equivalent of these existential challenges with the Climate Crisis and the struggles of democracy to survive in America and around the world.

Yet our arts critics want to act as if these catastrophes can be ignored. Business as usual. For me, the key sentence is Bachmann’s — “We have to find true sentences which correspond to the condition of our conscience and to this changed world.” We can attempt to bury our heads in the sand and not provide these sentences — in art and criticism — but that is a recipe for disaster, for remaining in the old world, spewing out reassuring messages that forsake our consciences. Critics and artists need to face reality: to discern the nefarious forces that stand in the way of transformation and restoration and to encourage those dedicated to making the necessary changes. We may not succeed — but it the right fight to have, and arts critics should be on the right side of history.

I hope this helps …

A word to Arts Fuse critics. I didn’t mean that every review needs to talk about climate breakdown or the fading of democracy. But that, from time to time, pieces should be written that grapple issues that the”arts pages” in the mainstream media are ignoring. The craze for keeping business as usual needs to be condemned. I offer some ideas in the column for commentaries and reviews that do the necessary work of “connecting the dots” — between money, escapism, and distraction from reality. Little of that is happening, and time is growing short. An international community committed to the planet’s survival (particularly among the young) is in the early stages of formation. Billions of people are going to have to stand up for the kind of change that will wrest the future from delusional power brokers who believe that planet offers infinite resources. The arts — and arts critics — should be part of that transformation.

That does not mean every arts review needs to be part of that project. My columns on the climate breakdown — and reviews of books and plays about its progression — are my attempt to do further that goal. But I reviewed Commonweath Shakespeare’s Much Ado and there was nothing about politics. But, when the opportunity arises to bring in reality — go for it.

Where do you get the idea that critics are “exiled in bunkers” away from political realities? If anything there has been a total takeover of the institutions by progressive politics, and the critics have been cheering it on almost to a one. I could point you to a dozen museum exhibitions over the last year that hit all the same beats as Lin’s. One of them was “Devour the Land” at Harvard, about which Sebastian Smee raved until he was frothing. The Young Critics Prize sponsored by AICA expressly states that “Climate Change and Social Injustice themes are of particular interest.” The Ford Foundation announced last year that not a penny would henceforth go out the door that didn’t somehow support social justice.

“Art is not about. Art is.” So said Walter Darby Bannard in his Aphorisms for Artists. Art is its own reality, and if there’s something generally wrong with criticism, it’s denial of that reality’s existence.

Let me see. One fine critic tells me that “Art Is Life.” Another tells me that “Art is.” I grant you the metaphysical virtue of the shorter definition. Unless you deny science and what is happening around the world, the climate crisis is not a “progressive cause” — it is a reality. How we deal with the ongoing destruction of nature may well be a matter of ideological argument — but there are pragmatic steps to take, such as to get off of fossil fuels as quickly as reasonably possible. If you feel that is progressive and thus to be shunned, enjoy the global sauna to come.

The visual arts have done more to deal with the climate breakdown. If you look at theater, film, music, and other areas, the emphasis is on “Art is” escapist entertainment. Most of our critics seem perfectly content with apathy, so I don’t see all that many reasons for you to be upset. Don’t worry, nobody wants to interrupt business as usual. Emergencies get in the way of marketing on both sides of the political divide. Things are going to have to get much worse (and they will).

As for life in the bunkers, the “Art is” crowd will need food and water to properly bask in their appreciation of art. That is a non-ideological reality that demands to be met — unless they will be reveling in the “reality of art” in the spiritual realm. The basics needed to sustain life may become considerably harder to procure as the earth’s population reaches 10 billion, as projected, by 2050. Perhaps, if we don’t take action, we should think about “Art was.”

Another aphorism of Darby’s: Art is entertainment.

Entertainments are not necessarily vulgar or empty-headed, though many of them are. Entertainment sometimes delivers a sublime experience of art-value, so we call it art. Criticism is a subsidiary entertainment that sometimes delivers literary value. There is nothing wrong with this.

What’s vulgar is this notion that art and criticism that doesn’t address the key issues of the time is escapist fluff. Certainly they may address such issues. But that address guarantees nothing, least of all art-value. I don’t review work I haven’t seen but no images of Lin’s work entice me to Smith College. These unremarkable-looking things are conveying a theme of climate urgency that I’ve already heard many thousands of times, in plain English. Message received, I don’t need to see the art now. I question whether it needed to be made, or whether it accomplishes anything other than gratifying the feelings of people who want to see their issues of greatest personal concern illustrated as art objects. Much of the social justice art has the same coating of oil on it.

As for the climate, a couple of months ago I listened to talk in which the speaker related that as best as he could tell from the data, global CO2 increases even at the highest rates theorized would be beneficial on net. As ought to have become obvious when a certain powerful health regime bureaucrat claimed to be science incarnate, our culture has developed quite a problem understanding what science may legitimately claim. Science doesn’t tell you what to value. Art can tell you what to value, but only by example, by succeeding as art, lest it devolve into propaganda.

Of course there is intelligent entertainment … I didn’t say there wasn’t. In fact, I would argue there isn’t enough of it. Neither did I insist that artists should just focus on social issues and that those who don’t should be drummed out of the art world. My argument is that arts critics should acknowledge reality. Why be so defensive?

Lin’s work moved me and others. To each his own. I am glad you have received the “climate breakdown” message loud and clear. You have accepted our predicament with surprising equanimity. Of course, we need the governments of the world to act on making considerable changes, so I hope they are not as blase.

Still, your reduction of the climate crisis to “social justice'” is troubling — we are talking about the survival of nature and ourselves. Perhaps “ultimate concern” might be a better fit? At least for millions, or perhaps billions of people? They may not have the convenience — sans food, water, soil, clean air — of being as bored with the issue as you are.

You don’t identify the speaker extolling the benefits of CO2– perhaps he was covered in the coating of oil you refer to? The overwhelming majority of scientists in the world disagree with the notion that pumping CO2 into the atmosphere is beneficial. I could refer you to books that clearly explain the physics behind what is happening. You are free to disagree and accept what I would argue is fossil fuel industry propaganda. But the rest of us (including artists who choose to) should be encouraged to grapple with the scientific evidence — and what is happening right before our eyes — and do what they can to help mitigate disaster. I don’t think we disagree, ironically. Art succeeds as art by telling us what to value — and I assume we both value life on earth.

The speaker was the brilliant polymath and libertarian anarchist David Friedman. He delivered an updated version of this 2013 talk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-yJ3K9fNos

This is someone using the IPCC’s own data in good faith, who accepts that change is occurring, and that it’s anthropogenic.

I didn’t say that climate change per se was a social justice issue. But the progressive understanding of climate change reduces it to a social justice issue, as it tends to come to the same conclusions every time: that the changes are assuredly apocalyptic, and we can only prevent them by directing government (presumed benign and free of capture by selfish interests) to bring the germane corporations to heel. The related environmentalism disdains solutions that include privatization of resources or nuclear power, that latter which is our fastest path out of fossil fuel use.

But that’s beside the point of the main one I was making, that the cure you’re suggesting for art criticism is in fact the disease. As far as visual art is concerned, the interestedness is acute and the related art and criticism are worse than ever.

Good to have the speaker identified — people can evaluate him. Friedman has his serious critics. I hope someone asks him when the “good ” effects of CO2 are going to kick in.

As I write, “the extreme heat and drought that has been roasting a vast swath of southern China for at least 70 straight days has no parallel in modern record-keeping in China, or elsewhere around the world for that matter.” Other intimations of the apocalyptic abound, from the growing decades of drought in the American West to the current killer floods in Pakistan. The current no doubt early estimate of damage: 4.6 million people affected, 300,000 homeless, 1000 dead, 90% of crops in sindh province affected.

The destruction of the Amazon rain forest ( “as much as 17% of the forest has been lost already, and scientists believe that the tipping point will be reached at 20% to 25% of deforestation”) and the continued heating up of the oceans (which will mean the decimation of sea life) may not be “assuredly” apocalyptic? That makes me feel so much better.Somewhat apocalyptic? Apocalypse lite? Not as catastrophic for the rich countries as it is for the poor ones? (Seems to me that if you are in the flooded area of Pakistan you are in the midst of an apocalypse.) Do we want to live in a semi-apocalyptic world? Only Jonathan Swift would be up to suitably satirizing such a (bleakly reassuring?) message. Again, by the year 2050 there is projected to be around 10 billion people. How will the beleaguered earth (which isn’t getting any bigger) nurture a population this size? Via magic wand? Many of those billions will be poor.

Also, as we wait for Friedman to pull CO2 out of a magic hat, concerned citizens should follow a law suit filed against ExxonMobil, which claims that the company did research, decades ago, that showed the horrific, harmful effects of pumping CO2 into the atmosphere — it is a probe that Exxon has been doing whatever it can to stop. The suit is going forward, and it may show that — like the deceptive cigarette companies — the mega-rich fossil industry knowingly, for the sake of profits and power, engaged in a “sophisticated, multi-million dollar campaign to sow doubt in climate science and downplay the public about the role its fossil fuels play in causing climate change.” No doubt Friedman will want to look over the research. We may have been lied to about global poisoning — by a private company!

As for the “disease,” I am afraid it is the current mania to fit everything into an air-tight ideological grid, including, perhaps tragically for nature and our future, the climate breakdown. There are no “progressive” or “conservative” solutions to the climate chaos. We need vigorous discussion and debate regarding pragmatic actions to take — which isn’t happening because everyone is stuck in a mind-deadening corner. Perhaps the solution will be a combination of nuclear energy and collective government action? (It is a global problem.) Perhaps there will be a mix of privatization and state action? It is going to take an enormous effort to mitigate the damage to come, and it will need to draw on the efforts of billions of people. (Some ambitious artists could try to wrap their minds around that.)

As for art, it is, as you wisely said, to impart values. And one of the responsibilities of arts critics (I would argue it is primary now) is to remind artists of the value of life on earth — particularly its fragility at this time and times to come.

Irreversible changes are taking place. And there are more to come. That is a fact. Without beauty, Alfred North Whitehead insisted, truth “sinks to triviality” — the good becomes becomes sterile, an empty concept. Arts critics should not reinforce sterility, but challenge it.

I was heartened initially to see you reference Carrie Battan’s review in the New Yorker of the new Beyoncé album Renaissance, and I dare to ask a few questions pertaining to that album. First, when did it happen that using the words ‘mother fu%%er’ became a norm? As many children (including her own) hear this, will it just become part of their language? She says it no less than four times in the first song. Clearly, Beyoncé is considered a goddess by perhaps millions and worshipped as such. What does it say that she lists seven luxury designer brands in that first song, giving them an outsized status just because she names them? Many speak to the brilliance and cultural significance of Beyoncé’s latest creation, and I have to wonder what kind of values are being passed on. It’s also of interest that no critics even mention the notion of how music can shape values, positively or negatively. We’ve come a long way from Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On?… or have we?

I was using the Beyoncé album to talk about the critic’s accusation that the culture was “inert” — I wanted to talk about how are arts critics are helping to make it that way.

You are raising another, but connected question — are critics doing their jobs? Are they evaluating? Or just rubber-stamping? I have not read enough of the reviews of the Beyoncé disc to answer that. But you are asking a powerful question — are critics raising issues of value? Or simply getting on a bandwagon?

Thank you for acknowledging that broadly speaking, both artists and critics have stepped away from considering values. I’m glad you care about that.

Meanwhile, I challenge you to find a print review or podcast of Renaissance that is anything but glowing. The Guardian (‘A Breathtaking Maximalist Tour de Force’), Washington Post (Beyoncé’s Renaissance was Made to Last Forever’), LA Times (Beyoncé’s Renaissance A Landmark Expression of Black Joy’), and the New York Times, (‘The Robust Return of Beyonce’) are just a few examples.

It was fascinating that a huge backlash occurred over her use of a word that offended many from the disability community, and more press was given about her decision to change that one word. No mention, however, of the multiple F-bombs.

A passionate piece published in The Stage from Michael Longhurst, artistic director of London’s Donmar Warehouse. The company is currently producing a new play, The Trials. We desperately need theater companies here to take the lead on climate breakdown — “the meta-narrative” of our time” — not to preview Broadway musicals. Our stages are marginalizing themselves by turning their backs on their responsibilities as artists and citizens.

It’s simple: the average art lover wants beautiful art. Yet the art critics have given themselves over to a delirious cheerleading of art that has abandoned beauty as a worthwhile goal. It’s true that art critics aren’t “living in the world the rest of us inhabit.” But the world we inhabit is one which needs beauty. The real problem is that art critics don’t have the bravery to say that a particular work of art is just *not good art*, a judgement that the public is quite willing to make on its own.

Some of the most beloved art movements — the Pre-Raphaelites and Impressionists, for instance — were concerning themselves with accurate, beautiful depictions of reality. Where are the art critics who are championing the heirs of these movements? Where are the critics who are defending with passion the worthwhile, beautiful new, in opposition to the profit-hungry, shock-value-glorifying tastemakers?

Where are the critics willing to break ranks with the avant-garde and the say, for instance “Mapplethorpe’s pictures are gross, Koons’ sculptures are boring, and Hirst’s dots are just dumb.” The common people can see the truth of those aesthetic judgments, and they see the critics as the pandering yes-men of the avant-garde — an avant-garde which is now turning its attention to progressive / social justice causes as fast as it can. The essay’s author might not be aware that such is the case, but until the critics re-establish themselves as voices of *aesthetic* criticism, they will continue to be marginalized.

What about truth and beauty? It is anything but simple. Yours is such a narrow way of looking at beauty. It is a complex issue, obviously, and generalizations about what the “common people” feel in one paragraph and “art lovers” in another begs the question.

For example, Elaine Scarry wrote that “to place oneself in the path of beauty is the basic impulse underlying education.” A strong argument has been made over the centuries that beauty and education are intertwined, and what we need to learn is not always going to be what’s conventionally beautiful to “the common people” or immediately acceptable to “common” critics. Alfred North Whitehead believed that if education does not lead to “an elation of feeling” it will have failed in its aim. And if education does not cultivate the love of beauty through art, it betrays its mission. Without beauty, Whitehead insisted, truth “sinks to triviality” — the good becomes becomes sterile, an empty concept.

So, to get back to my argument in this column, we need beautiful art (subject to critical evaluation and community dialogue) to inform us of an issue of ultimate concern — climate breakdown. The survival of the species is not just a political matter, though ideologues, particularly on the right, want to make it that. We all need potable water, healthy food, and clear air to breathe. We need to do what is needed to sustain 10 billion people by 2050 on a planet that is not getting bigger.

My argument for what critics should do but aren’t: demand works of art be made that make the perils of the climate crisis — and the necessity to do what we can to preserve a ravaged nature — passionate and real. To invigorate the good through art. Argue as often as you want that Jeff Koons is bad art — waging culture war parlor games it is not going to save us from a world of climate chaos.

Not to be an “art for art’s sake” guy here (heaven forfend!), but what is the role of art as entertainment, as providing pleasure in a tumultuous (and, as read here, dying) world? Even as a relief from personal pain. How does art engage with the world while still being an expression of personal concerns and struggles. On the one hand, we have the Wooster Group’s staging of Bertolt Brecht’s “The Mother” (not to be confused with “Mother Courage”), one of Brecht’s “learning plays,” written for a specific political purpose. And the dealing with personal and political themes in “Philip Guston Now” (reviewed in the Arts Fuse, https://artsfuse.org/255444/visual-arts-commentary-philip-guston-and-the-impossibility-of-art-criticism/). Is there a place for “honest” art, which perhaps doesn’t explicitly reflect social disaster but acknowledges “the human condition” by, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, a refusal to talk falsely. Or as Greil Marcus wrote about rock and roll, when art “is not simply a balance sheet, but a matrix of voices and values.” (See Greil Marcus’s essay from the ’90s, NOTES ON THE LIFE & DEATH AND INCANDESCENT BANALITY OF ROCK ‘N’ ROLL , which quotes Jon Landau on that “John Wesley Harding” bit: https://greilmarcus.net/2015/04/10/notes-on-the-life-death-and-incandescent-banality-of-rock-n-roll-0892/

” Is there a place for “honest” art, which perhaps doesn’t explicitly reflect social disaster but acknowledges “the human condition” by, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, a refusal to talk falsely.” There sure is. Arts critics don’t agree (thankfully) and the idea that they have a magic wand to change the zeitgeist is absurd. The arts will continue to give pleasure and that is a good thing. I would add that, for me, that pleasure should help give us the strength, confidence, and spiritual savvy to do what is needed to be done during a time of crisis. It should direct us back to the world, to keep ourselves and our leaders honest.

I will push back a bit on your characterization, as “read here, dying) world.” Climate breakdown is an elemental part of the”human condition.” It is a matter of survival — for us and the living earth. For me, the key sentence in my column is “We have to find true sentences which correspond to the condition of our conscience and to this changed world.” We are living in a changed world that is going change even more radically. The latest report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is that governments are missing their targets regarding CO2 and other issues. And things are getting worse at a faster rate than scientists have predicted. According to a February 22 National Geographic article:

“The effects of warming are already driving people from their homes as seas rise, as well as killing trees and animal species. We can adapt, but also urgently need to make deep and immediate emissions cuts to head off even worse impacts, experts say.”

“The poor, the very young and very old, ethnic minorities, and Indigenous peoples are at most risk. And while measures to limit the impact of climate change do exist, the only truly meaningful step is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible.”

The earth is slowly becoming unrecognizable. So yes, it is a dying world. (I will paraphrase Dylan, the world not busy being born is busy dying.) How should arts critics react to that reality? Ignore it as they have been? Call for a “greening” of the arts? It is a question that has not been — but should be — asked. We are entering into new territory, whether we like it or not.

Arts “criticism,” namely, reviews, have been tremendously destructive to the arts, by seeking out negative values to ascribe to the subject and then by not writing about things at all. The NY Times in particular, has been the greatest enemy to the arts, while writing about them more than most newspapers. A rave review, even a positive quote, could build a career, particularly for a solo recitalist, but now, they won’t even review a solo recitalist, hence, no more debut recitals. A solo classical-music recital is equivalent to an actor’s one-man show, and perhaps even more challenging, as a variety of music must usually be presented. It is a foundational experience of the art of music, as much or moreso than a chamber music program or an orchestral program, because they all begin with the individual learning to perform. Wikipedia, the amateur encyclopedia continues this destruction by ensuring the inclusion of negative comments on individuals in their entries. The fact that most critics are not actual musicians or artists makes their “insights” often irrelevant. The idea that one can truly know an art and have valuable things to say without being a practitioner is greatly overestimated. An armchair observer really has no value at all beyond conversation. An academic is more destructive, being able to misinform their students. The entire “period instrument” movement is nothing more than an academic hoax that destroyed other group’s ability to perform baroque music, classical-era music, and now they even have the gall to invade 19th-century music. Virgil Thomson gave the best advice on being a critic in a time when many of them were composers, but it is hardly followed today. Perhaps this is why we have no national arts publications. There aren’t any writers good enough to fill them?

Too much hyperbole and too many contradictions in this comment. The NYTimes ascribes too many “negative values” — what are they? — but doesn’t review enough solo recitals. Apparently, reviews are supposed to be positive and only written by practitioners, who are, of course, impeccably disinterested. (Consider critic/composer Virgil Thomson’s conflicts of interest.) And if criticisms are rendered, they should be kept out of Wikipedia. The sad fact is that arts criticism is fading in our mainstream media for many reasons — economic, cultural, and editorial. I have written about the decline elsewhere. There is talent out there — you can see it in blogs and small online magazines, Just no ladder to climb or opportunities to be had.

As for Thomson, a very fine classical music critic, he was concerned with how innocuous most reviews had become. From his 1974 article “The State of Music Criticism”:

There will always be those who pine for the bland old days …

Let’s give the last word to James Baldwin: