Theater Commentary: January 6 — What About the Children?

By Joan Lancourt

Despite a seven-year record of artistic, social, educational, and organizational success, Junior Programs has, until now, been a forgotten chapter in the history of America’s children’s theater. And we desperately need to remember that chapter now.

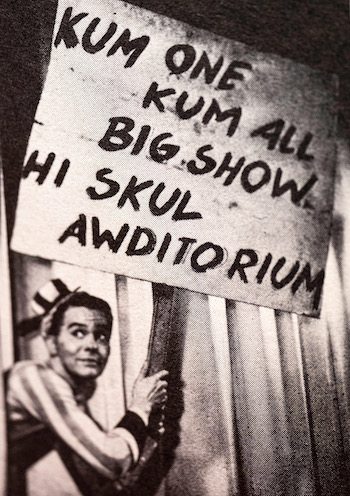

Junior Programs, Inc. (1936-43) in action. Photo: courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

On January 6, 2022, President Biden told America its democracy was in serious jeopardy. On June 9, 2022, Congress began public hearings investigating the assault on the US Capitol. Both events indicate that as a nation, we are faced with a battle for the “soul of America.” For democracy to prevail, constant vigilance is required; and if democratic values are to endure, they must be deeply rooted in our next generation of citizens. Inculcating democratic values, and teaching democracy to the nation’s youth is a tall order, requiring more than straightforward pedagogy. A large dose of creativity is also necessary, and what could be more creative than using live theater to achieve this critical outcome?

“Live theater? Why live theater?” Quite simply, the best theater artists are masterful storytellers, and stories are a highly effective way to internalize a society’s values, particularly with children. Stories help them connect with each other and make meaning out of the world around them. Theater literally brings a story to life: visually, aurally, emotionally, and intellectually. It can make your eyes widen, your heart beat faster, and your palms sweat. At its most effective, it engages your mind and your heart: live actors make it easy to believe that the drama is real, that you are part of it, and that in some way, you and the story are connected.

It doesn’t hurt to remember that theater has been part of the democratic process since the sixth century BCE. Of course, neither the benefits of democracy or its need for constant vigilance sprang full blown from the head of Zeus. The citizens of Athens regularly gathered in their amphitheaters and used drama as the collective means for interrogating and considering how well — or poorly — their democracy expressed their social, civic, and political values. Regrettably, since then, theater and democracy have traveled widely divergent paths, to the detriment of both. Still, the primal connection has not been forgotten: in a 2018 TED talk, Oscar Eustis, of New York’s Public Theater, reminded us of this intimate relationship when he argued that theater supplied the three basic tools of democratic citizenship: a stage for the collision of competing ideas; a format that creates community; and a form of storytelling that engenders empathy. Given democracy’s current fragility, and the current trajectory of our democratic system, it would be wise for us to take him at his word.

There is already a potential infrastructure for applying Eustis’s prescription to the next generation: Theater for Young Audiences (TYA). There are now about 130 such theaters, but it is only in the past decade or so that these theaters are offering more than colorful children’s entertainment, serving up Charlie Brown’s Christmas, Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, Shrek, The Musical, and a broad range of classic children’s stories. There are signs of dissatisfaction with this setup. A 2019 National Endowment for the Arts report on the TYA, the NEA put its finger on several barriers that stand in the way of TYA’s continued evolution. At the top of list: a “style of either/or thinking” that emanated from various professions, including funders, that viewed the performing arts and education as primarily separate disciplines. While the two occasionally overlap, few TYA theaters are equally committed to both. Whether the two could, in practice, be successfully combined remained an open question.

That is, until the recent rediscovery of Junior Programs, Inc., (1936-43). It turns out one of the earliest pioneers of professional theater for children entered from stage left.Their explicit purpose was preparing the next generation for the task of sustaining democracy through a marriage of the performing arts and education. According to prominent children’s theater historian Nellie McCaslin, Junior Programs was “one of the finest companies in the history of children’s theatre in America … [and the] crowning achievement of the period.” Despite a seven-year record of artistic, social, educational, and organizational success, Junior Programs has, until now, been a forgotten chapter in the history of TYA. Despite having introduced four million children across the nation to live theater, ballet, and opera — most, for the first time— its three professional touring companies, which broke audience attendance records, were forced to close in 1943 because its performers were being drafted. Also, gas and tires for its touring scenery trucks became unobtainable. Too soon, the stellar achievements of Junior Programs faded from view.

A scene from Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A: “And Mr Dumphrey is thrown out.” Dumphrey is the local strong man trying to take over the town. Doodle helps the citizens organize and remove him. Photo courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

Just what did Junior Programs do to promote democracy, and how was it able to do it? One major key to their success was how they integrated their performing arts productions with an extensive set of grade-appropriate curriculum units commissioned by an Educational Advisory Board composed of the leading educational experts of the day. These curriculum units differed in a very important way from the TYA’s focus on “teaching artists” as providers of special programs outside the standard curriculum. And they were a departure from the American Alliance for Theatre Educators’ (AATE) concentration on performing arts educators. Sent to the local schools three months prior to a scheduled performance, these units provided regular classroom teachers in almost every subject-matter area (including Phys Ed, Home Ec, and Shop) with a range of curriculum units and other resources they could use as part of their regular lesson plans to engage their students in substantive subject-matter with specific pedagogical goals. The teachers loved the resources and, by the time the production arrived, the youthful audience was well versed in a broad range of issues (history, literature, social studies, cultural diversity, economics, political science, as well as drama, music and dance, etc.) that would be addressed in the performance. Pedagogically, the stagings magically wove together disparate topics into an organic and compelling whole. The National Federation of Music Clubs affirmed the success of this synthesis. “Now in its seventh season, Junior Programs has … become an American institution.”

Second, the company’s Credo explicitly articulated their belief in a symbiotic relationship between the arts and democracy. Junior Programs believed the arts should be actively used to guide the young audience toward democratic ideals. Decades ahead of its time, the troupe treated the performing arts as an essential contributor to a flourishing democracy.

“In order that American children may be guided to the preservation of democracy, freedom, and the world’s cultural heritage … Junior Programs, Inc. has devised a Creed of Entertainment for Children in a Democracy:

“SINCE music, drama and all the arts … flourish best in a democracy.

WE BELIEVE that all American children, regardless of race, creed, or social or economic status, should have the benefit of inspiration by the finest professional artists.

WE BELIEVE that these performances should arouse the children’s wholesome laughter, help develop their personalities and artistic tastes, and guide them towards democratic ideals.

WE BELIEVE that the artistry of all races and nationalities undistorted by bigotry, [and] hatred … should be made available to all children.”

This Credo informed their productions and their pedagogy in two ways. Its final production, Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A.,” was specifically written to answer the question, “How do we teach children about Democracy?” According to founder Dorothy McFadden, “Doodle Dandy will make them think about the meanings of our freedoms, [and] the responsibilities of democratic citizens. Unless they understand these, they will not be ready to take their part in making freedom work.” In a 1943 NY Times article, “Writing for the Kids,” Junior Programs’ artistic director and author Saul Lancourt stated, “In treating the theme, we felt it best to go back to the … fundamentals upon which our country was founded and relate these … to what might happen if some minor league Fuehrer tried to enthrone himself in a representative American community. In this way we were able to give our audiences a starting point within the realm of their own experience.” A press release quotes the US Office of Education’s assessment: “The aim is to keep … alight a flaming devotion to the cause of democratic freedom.”

Dance Magazine spotlighted the ways in which the play made democracy exciting and fun. “The story sets out to sell the kids on Democracy and by George (Washington), it succeeds … [and] manages to keep them hilariously amused…. The first scene is laid in Heaven…. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson … look down to earth and see how careless America has become about its precious Democracy. They decide to send Doodle Dandy down to earth to help the citizens who still value Democracy…. The folks in the play finally decide to win their bulldozed citizenry back to democracy by giving a local entertainment that will explain the necessity of democracy and how to make it work…. The real audience becomes the audience of local citizenry, and is treated to one of the most charming programs, which dances out in the simplest, most basic and entertaining manner the whys and wherefores of democracy…. But the most remarkable thing of all is that we don’t realize we are being given a sermon because it is such a knock-down, carry-you-home good play, with catchy music and excellent dancing … and the most entertaining and convincing presentation of democracy we’ve seen yet.”

A scene from Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A: Doodle’s Lucky Star is helping him down to earth. Photo courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

A 1942 NY Times article identified specific characteristics that enabled the play to connect with its audience: “[It] is simply told … acted without pretension … [and] Mr. Lancourt has staged the affair with a disciplined hand … although there is much motion, none is wasted. The interpretive dances by Ted Shawn were a childish delight.” Lauded as a “Play Building Good Citizenship,” the Nashville Tennessean called Doodle “a story of the gallant fight for freedom by children [emphasis added] of a typical American community.” This critical sense of “agency” was echoed in the Trenton New Jersey Times: “[E]mploying all the color, fun and mystery of the theatre, [Mr. Lancourt shows] how children can democratically join together and oust a would-be dictator from their town.” The Ledger Enquirer also tells us, “The play was designed to make the people think for themselves and accordingly, it made our audience of little people think and answer the questions … thrown from the stage…. [Doodle’s] dancing was a suggestion of mischief which placed him in each child’s heart immediately…. The tunes were lively and patriotic and made you want to sing with the characters.” Finally, the Milwaukee Journal said, “it had the youngsters shouting for democracy with as much vigor as they yell for a hit at a ball game…. Fisticuffs, excitement, humor and slapstick combined [and] … there was a sympathetic guffaw when it was discovered that Doodle was as poorly versed in spelling as he was well versed in the tenets of freedom … [and he] loved a good time but … prized freedom even more.”

The Christian Science Monitor identified additional factors such as direct engagement and not underestimating the intelligence of children: “Mr. Lancourt is never condescending to his youthful audience, and he has written the play in a way that makes it clear that the children themselves have agency in the preservation of Democracy. He does everything possible to actually engage the youthful audience…. Doodle asks the audience a direct question and waits for an answer…. And the audience invariably shouted an answer.”

A scene from Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A: Dumphrey announces that “the affairs of Springville are safely in my hands whether you like it or not.” Photo courtesy of Jerold Lancourt.

The second way Junior Programs took its Credo seriously was in the plays it commissioned. Reward of the Sun God established the value of Junior Programs’ new approach to children’s theater. The Reward of the Sun God, supported by its array of curriculum units, offered a much-needed corrective to the Hollywood narrative of Native Americans as “primitive savages.” Not only did it provide a compelling, empathic, and positive story of a widely stigmatized culture, the production eschewed dogmatic or didactic messages. The American Women’s Association Bulletin lauded the production as “definitely designed to give the children an awareness of the attractive and interesting characteristics, histories and civilizations of other countries and races” and the Manitowoc, Wis. Herald Times concurred. “Instead of the typical ‘blood and thunder’ children think of in connection with Indians, there was, in The Reward of the Sun God the poetry and religion and lore that more truly typifies a people.”

Reward was soon followed by The Emperor’s Treasure Chest, a rollicking tale of Brazilian children. Replete with authentic costumes, dances, and music, again supported by a suite of curriculum units that included a pointed comparison of Brazilian and American forms of slavery, the musical was a direct challenge to the negative Hollywood portrayal of Latinx people as either asleep under a sombrero or as villainous outlaws attacking stagecoaches. And Junior Programs’ penultimate production, The Adventures of Marco Polo, again with a supporting curriculum, countered the negative Hollywood image of the inscrutable, wily, alien Chinese. Instead, the script acknowledged China’s scientific achievements, artistic refinement, and, at the court of Kublai Khan, its inclusive cultural diversity.

William Vickery of the Service Bureau of Intercultural Education provides an excellent summary of the Junior Programs’ approach to education, the performing arts, and democracy: “[T]here is an acute need for developing [an] understanding … of diverse national and racial backgrounds. Propagandists … have been trying desperately to destroy our national unity by appealing to existing hates and fears…. Intercultural education has … two major objectives: First … to develop in children who belong to the dominant group respect and liking for the members of minority groups. This probably can best be done by correcting false impressions based on misinformation, and by accepting that a person’s being a good American has nothing to do with, say, the color of his skin or the nationality of his father. Second, it attempts to give children of minority groups the feeling that they ‘belong’; that their people are helping to build an American culture, and that the more sources from which American civilization draws, the better … it will become.”

There’s much more TYA and AATE could learn from a deeper investigation of Junior Programs’ experience: of how it saw artistic and educational problems and risks as opportunities to innovate and learn. Their unique business and organizational model not only substantially engaged the local communities in which the company performed, but also managed to keep ticket prices low. But for now, why not consider what we could achieve if just half of the TYA/AATE institutions created deeper partnerships with their local schools. That partnership could be used to specifically amplify, articulate, and support America’s democratic aspirations — its ideals of equality and fair play, of community responsibility and solidarity, of fighting for justice, of valuing diversity and inclusiveness. Above all, using theater to reinforce the preciousness of American democracy — and the work that is needed to preserve it. As many who saw Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A. commented, protecting democracy is an unending battle, one in which the next generation will need to be enlisted. Let’s use a marriage of our performing arts and educational systems as an always dependable way to win that fight.

Joan Lancourt, PhD, is a retired organizational change consultant, a former theater board chair, and a recent chair of the Brookline Commission for Diversity, Inclusion & Community Relations. She consults and has run workshops on increasing theater board diversity and community engagement, and is currently writing a book on Junior Programs, Inc, 1936-43, one of the first major professional performing arts companies devoted exclusively to theater, opera, and dance performances for young audiences.