Classical Album Review: A Quietly Powerful Work for the Lorelei Ensemble Pays Homage to an Anti-Nazi Activist

By Ralph P. Locke

Thankfully, there is no melodramatic black-and-white in James Kallembach’s fascinating 36-minute work, first performed at Boston University by the Lorelei Ensemble in 2017.

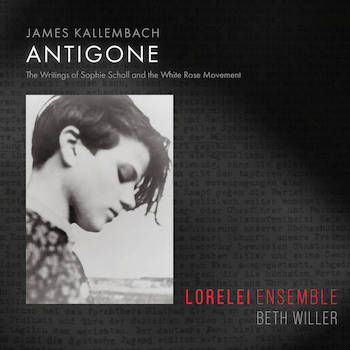

James Kallembach: Antigone (The Writings of Sophie Scholl and the White Rose Movement)

Lorelei Ensemble, cond. Beth Willer.

New Focus Recordings FCR333—37 minutes.

To purchase, click here.

An immensely talented women’s singing group that calls itself the Lorelei Ensemble has come out with a world-premiere recording of a fascinating piece by Chicago-based composer James Kallembach. The full title of the work indicates the work’s intriguing premise: Antigone (The Writings of Sophie Scholl and the White Rose Movement). The work was commissioned by the Lorelei Ensemble and Carson Cooman (a renowned organist and composer) and was first performed by the Lorelei Ensemble at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel. In it, Kallembach alternates between three kinds of texts: writings of Sophie Scholl and other members of the anti-Nazi “White Rose” movement of the early ’40s, passages from Sophocles’s Antigone (from the fifth century BC), and a Catholic responsory text (in Latin) freely derived from some lines in the book of Isaiah.

An immensely talented women’s singing group that calls itself the Lorelei Ensemble has come out with a world-premiere recording of a fascinating piece by Chicago-based composer James Kallembach. The full title of the work indicates the work’s intriguing premise: Antigone (The Writings of Sophie Scholl and the White Rose Movement). The work was commissioned by the Lorelei Ensemble and Carson Cooman (a renowned organist and composer) and was first performed by the Lorelei Ensemble at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel. In it, Kallembach alternates between three kinds of texts: writings of Sophie Scholl and other members of the anti-Nazi “White Rose” movement of the early ’40s, passages from Sophocles’s Antigone (from the fifth century BC), and a Catholic responsory text (in Latin) freely derived from some lines in the book of Isaiah.

Kallembach’s purpose here is to let the courage of Sophie Scholl and her brother Hans, who were guillotined by the Nazis in 1943, resonate with the courage of Antigone in the ancient Greek drama. She insisted on burying her brother outside the city gates for the sake of his immortal soul, though the ruler of Thebes, Creon, ordained that she not do so because the ruler had chosen to honor Antigone’s other brother. (The two young men had just died in a civil war.)

Scholl’s poetic reflections, and the hortatory calls from additional White Rose pamphlets, do echo strongly when set against the determination of Antigone to do what is right, at risk to her own life. Kallembach is also (like Jean Anouilh in his 1944 play Antigone) aware enough to lend Creon’s statements their own moral weight. There is thus no melodramatic black-and-white in Kallembach’s 36-minute work but rather a series of reflections on the agony of human choice in risky and sometimes ambiguous situations.

The result is a fascinating but low-contrast work, performed mostly at a moderate tempo, and with only a few “colors”: women chorus, sometimes a cappella, sometimes accompanied by four cellos, and alternating at certain moments with a soprano solo or, once, a trio of women’s voices (to sing a stage direction for us).

The musical style often evokes the calm, diatonic world of Renaissance choral music, though sometimes (as in the untexted singing that opens the work) also recalling American pop music or (as in the Epilogue entitled Sophie’s Dream) the pandiatonic harmonies of Poulenc. The words are not always immediately understandable because they are set, and sung, in an unemotional manner, as if we are in the midst of a religious ritual. But, with the text booklet in hand, one’s head buzzes with thoughts and ever-timely questions about individual freedom, mutual responsibility, and codes of social behavior and transgression. The cello quartet often extends the expressive range of the work, suggesting layers of violence and sadness that the voices leave unuttered.

This video offers an excerpt from the work:

And this one gives the conductor’s and composer’s view of it:

One oddity in the work: the responsory text is given in the booklet (and, so far as I can make out, is sung) as “Ecce quomodo moritur / et nemo percipit corde…/ Erit in pace memoria eius.” This version omits the subject of the sentence: “justus” (the righteous one). The translation, by contrast, includes the missing word, giving the first line as “Behold how the righteous one dies…” (my emphasis).

Presumably Kallembach didn’t want to include a masculine noun because Sophie Scholl was a woman.

But one can surely understand “justus” as implying a “righteous person” (homo justus), rather than necessarily a “righteous man” (vir justus). I wonder if the composer might like to tweak his score to restore the crucial missing word justus, which is not only needed to make grammatical sense but also does describe Sophie Scholl so well. This one powerful word (“righteous” or, as one might also translate it, “upright”) deserves to stand as a goal for the rest of us in this troubled world and troubled country — both so evidently in need of repair.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).