Book Review: “Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird” — A Writer’s Life

By David Mehegan

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the Black American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, and this new biography does a thorough and compelling job in telling the story of a remarkable and partially tragic life.

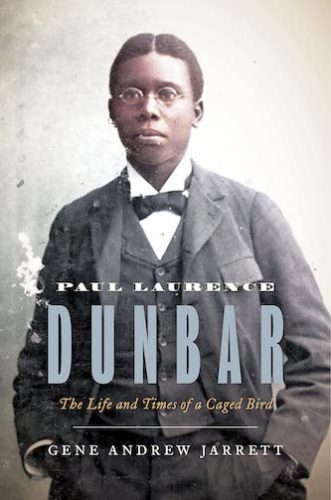

Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird by Gene Andrew Jarrett. Princeton University Press. Illustrated. 544 pp. $35.

Paul Laurence Dunbar was not the first Black American poet, but was the first to become famous, to have a large audience, to make a general success as a writer and public reader. Known and admired by Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, and Theodore Roosevelt and praised in print by critic William Dean Howells, he was a pioneer as a self-made man of letters. These alone are reasons enough for a new biography and Gene Andrew Jarrett does a thorough and compelling job in telling the story of this remarkable and partially tragic life.

The caged bird of the title is from Dunbar’s best-known poem, “Sympathy,” from his 1899 collection, Lyrics of the Hearthside. The last stanza begins,

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore, —

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings –

I know why the caged bird sings!

It is one of the ironies of Dunbar’s life that these words are best known as the title of the autobiography of Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. She credited Dunbar and often recited the poem from memory; still it is poignant that the only one of his hundreds of verses well known today was made famous by somebody else.

Accustomed as we are to the idea that the continued disadvantage of Black folks is in part the residual backwash of slavery, 160 years later, it is notable to see distinction achieved in just one generation. Paul Dunbar’s parents were slaves (Jarrett does not substitute “enslaved person” for “slave”) in Kentucky. His mother, Matilda Murphy, moved to Dayton, Ohio, after emancipation. His father, Joshua Dunbar, first escaped slavery to Canada, then returned to volunteer with the 55th Massachusetts Regiment, the second to enlist Black soldiers after the more famous 54th. At war’s end, he settled in Dayton, where he met and married Matilda, a domestic worker. Joshua was a skilled plasterer and a troubled, sometimes abusive alcoholic. The marriage did not last. Paul, born in 1872, leaped ahead despite a tumultuous home life. He excelled in segregated primary schools in Dayton. In 1887, segregated schools were abolished in Ohio and the talented boy went to Central High School.

Accustomed as we are to the idea that the continued disadvantage of Black folks is in part the residual backwash of slavery, 160 years later, it is notable to see distinction achieved in just one generation. Paul Dunbar’s parents were slaves (Jarrett does not substitute “enslaved person” for “slave”) in Kentucky. His mother, Matilda Murphy, moved to Dayton, Ohio, after emancipation. His father, Joshua Dunbar, first escaped slavery to Canada, then returned to volunteer with the 55th Massachusetts Regiment, the second to enlist Black soldiers after the more famous 54th. At war’s end, he settled in Dayton, where he met and married Matilda, a domestic worker. Joshua was a skilled plasterer and a troubled, sometimes abusive alcoholic. The marriage did not last. Paul, born in 1872, leaped ahead despite a tumultuous home life. He excelled in segregated primary schools in Dayton. In 1887, segregated schools were abolished in Ohio and the talented boy went to Central High School.

High school would be the limit of Dunbar’s formal education, but he made the most of it, inhaling deeply the English classics and American poets of his time. He knew early that literature would be his love and began to write poetry as a boy. At Central he was diligent and became co-founder of a short-lived newspaper for Black Daytonians, the Dayton Tattler (the other co-founder was his friend and classmate Orville Wright, before he and his brother Wilbur got interested in flight).

Soon after graduation (at which he delivered a valedictory poem), Dunbar set to work to become a writer. He wrote constantly, submitting poems to newspapers and magazines, while holding menial jobs, such as elevator operator. In time, his poems began to find acceptance, and in 1892, age 20, he published his first collection, Oak and Ivy. By the end of his short life, he had published 435 poems in 14 collections, four novels, four collections of short stories, many essays, and the libretti of several musical theater productions.

A key accelerant to his career was a laudatory review of his collection Majors and Minors in the June 1896 Harper’s Weekly by William Dean Howells, so-called “Dean of American Letters.” The well-meaning Howells lavished praise on Dunbar’s talent, which in a stroke made him a national literary figure. Yet the benefit to Dunbar was compromised by Howells’s implication that his true achievement was in his poems about Black life, especially those in dialect.

“He calls his little book Majors and Minors,” Howells wrote, “the majors being in our American English, and the Minors being in dialect, the dialect of the middle-south negroes and the middle-south whites; for the poet’s ear has been quick for the accent of his neighbors as well as for that of his kindred.” He continued that Dunbar was “the first man of his color to study his race objectively, to analyze it to himself, and then to represent it in arts as he felt it to be.”

While Dunbar was thrilled at this acclaim and the national stature (and access to mainstream publishers) the praise conferred, he eventually came to resent its patronizing particularization of his talent, its naming of him as the first poet of Black life. (Thus ignoring many earlier Black writers in and outside the United States.) “Allow me to present my friend, Mr. Paul Dunbar,” Howells wrote to his Scottish publisher, “the first of his race to put his race into poetry.” In private conversations, Jarrett writes, “Paul condemned Howells’s perception that race conditioned the excellence of literature.”

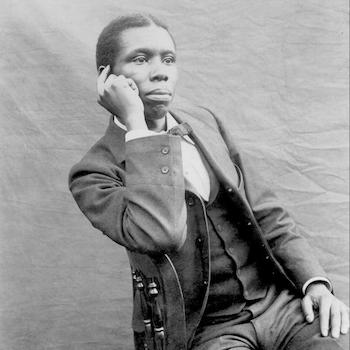

Poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar.

This would be a frustrating pattern throughout Dunbar’s career. When he would publish poems in both standard and dialect English, critics would praise the dialect and dismiss the rest, apparently irritated by Dunbar’s presumption that he could stray from the literary plantation. His ordination as specifically a Black poet was a kind of glass ceiling. He had no ambition to be a “race man,” a mensch or model. His goal was not to uplift “his race.” He just wanted to be a successful writer, to win the acclaim that white writers had garnered for the excellence of their art. His fame led to connections — although it seems not real friendships — with such luminaries as Howells, Ida B. Wells, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Theodore Roosevelt. Yet it seems that he always remained an outsider — never an academic or an influential critic like Howells, nor much of a money-maker, never a lionized figure in literary society. Yet he never stopped working, producing, and hustling.

The poignancy of his limitations as a literary figure in his own time was intensified by his personal problems, which damaged his reputation. He was increasingly alcoholic, misbehaving in public, and had an eye for women (which he did not hide), even during his marriage to the brilliant Alice Moore. Drink could make him violent. During their courtship, in 1897 he got drunk and apparently raped Moore. In an apologetic letter, he wrote, “I have dishonored you and I cannot forgive myself for it.” Somehow she forgave him, though, and married him the next year. He proved to be incorrigible. A severe beating he gave her while drunk (including kicks to her abdomen) in 1902 effectively ended the marriage. They had no children. Four years later, his health failed and tuberculosis killed him, age 33.

Biographer Gene Andrew Jarrett. Wiki Common

The writing of Gene Jarrett, professor of English and dean of the faculty at Princeton, is straightforward and clear, if a bit ponderous at times. He is a cautious scholar and relies carefully on primary sources. The notes to the book are extensive; it appears that no stone in Dunbar’s life is unturned. However, one might wish for more context. While the subtitle refers to the poet’s “Life and Times,” Jarrett writes relatively little about the Gilded Age in which Dunbar grappled for success, including the world that Du Bois in 1903 famously and bitterly chronicled in The Souls of Black Folk. Lynching is not mentioned, nor is the systematic exclusion of most Black people from the centers of society. The book is pretty much all about the exceptional Paul — as Jarrett calls him throughout–– and secondarily about Alice Moore Dunbar (whom Jarrett says deserves her own biography).

Jarrett does not give much critical treatment of the poetry itself, other than to cite Dunbar’s “mastery of literary genres — the Western lyric, the Romantic poetry of England, the ‘Fireside’ or ‘Schoolroom’ poetry of the United States, the realism and naturalism of American fiction, the racial uplift of African American literature, and the dialect of informal English.” Mastery of styles aside, Jarrett does not assert that Dunbar was an innovator. In tone and structure, much of his verse does resemble the “Fireside” writers, the likes of Longfellow, Whittier, or Oliver Wendell Holmes. After an 1899 visit to Colorado (in hopes of healing his lungs), he wrote a poem about it:

Golden glow of the morning

Over the snowcapped heights,

Not a cloud between; and the wondrous scene

Sets all my griefs to rights.

For rage seems poor and petty

In sight of the sun-kissed peaks,

And I have no care for the pain we bear

Nor the tears that dew our cheeks….

The dialect poems, for which Dunbar was celebrated in his day and of which he was as proud as those he wrote in standard English, would make many contemporary readers squirm and think of blackface minstrelsy. For example, here’s a stanza from “When de Con’n Pone’s Hot” about the appeal of hot cornbread:

Dey times in life when Nature

Seems to slip a cog and’ go,

Jes’ a-rattlin’ down creation,

Lak an ocean’s overflow;

When de worl’ jes’ stahts a-spinnin’

Lak a picaninny’s top,

An’ yo’ cup o’ joy is brimmin’

‘Twell it seems about to slop,

And’ you feel jes’ lak a racah,

Dat is trainin’ fu’ to trot

When yo’ mammy says de blessin’

An’ de co’n pones’ hot. …

While Dunbar was frustrated that these were the only poems that white critics and editors liked or wanted, he intended for them to employ an authentic voice, just as we likely today would hear in the voice of a hip-hop artist. Even in his own time, though, there was discomfort with it. Poet, lyricist, and activist James Weldon Johnson wrote years later, “I got a sudden realization of the artificiality of conventionalized Negro poetry, of its exaggerated geniality, childish optimism, forced comicality, and mawkish sentiment; of its imitation as an instrument of expression to but two emotions, pathos and humor, thereby making every poem either only sad or only funny.”

This is a long book about a short life, and while it is broad and deep in scholarship, this reviewer found its greatest impact in what it does not say, at least not explicitly. Jarrett never writes that Dunbar’s life and career were ruined by racism, although he lived in the Jim Crow world. David Blight’s prizewinning biography of Frederick Douglass does not stint in detailing the insults and outrages that great man endured throughout his life. But if those happened to Dunbar, they don’t get much attention in this book. Not that he could have avoided them — Jarrett does report Dunbar’s frustration at Jim Crow train cars. But it seems that the biographer does not want to overstress racism as the central fact of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s life. Racism did not prevent him from writing, publishing, marrying, traveling, and owning homes. As an on-again, off-again ally of Booker T. Washington (who famously believed that Black people should stick to trades and manual work), he was not an outspoken political crusader for justice and equality in the manner of Wells, Du Bois, or Douglass. It seems he never doubted his own equality. He just wanted to be, and insistently was, a writer.

David Mehegan is the former Book Editor of the Boston Globe. He can be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.

Tagged: Black dialect, Black poet, Gene Andrew Jarrett, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Princeton University Press