Book Review: Europe’s African Loot

By David D’Arcy

Africa’s Struggle for Its Art usefully charts the prequel to current campaigns pressuring for the return of colonial plunder.

Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Post-Colonial Defeat by Bénédicte Savoy. Translated by Susanne Meyer-Abich. Princeton University Press. 240 pp., $29.95.

Much of sub-Saharan Africa’s artistic heritage is not in Africa.

Bénédicte Savoy opens her book Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Post-Colonial Defeat with some revealing numbers. The British Museum holds sixty-nine thousand objects from sub-Saharan Africa. The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, has one hundred and eighty thousand. The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin has seventy-five thousand. Major museums in Europe hold more than half a million objects. That number includes bones and skulls.

There are more African objects in the Musee du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris than in all the museums in the US.

Since 1960, African countries have demanded that works from European institutions be returned. Calling that process slow is like saying the Sahara is sandy.

Restitution is a word that many have learned in the last few years. In the museum context, it means returning property, usually stolen property, often stolen art, to its rightful owners or their heirs. That stolen art was seized, often violently, in lands that European countries conquered and colonized in the 19th and 20th centuries. It also refers to art that was seized from Jews during the Nazi era.

For decades, calls for restitution of colonial plunder were eclipsed by, even buried under, claims for the return of art looted by the Nazis. In some cases, the victims of those thefts were still alive. Auction houses established restitution departments to sell Nazi-looted art that had been returned, often at record prices. Yet African objects carried off by European invaders were just as stolen.

There’s been a shift in recent years. Concern and outrage over monuments associated with slavery and colonial rule has extended to objects of plunder. Hence the renewed attention to works like the Benin bronzes. These carvings, casts, and reliefs date back to the 16th century and were taken out of Africa after a murderous British raid destroyed the city of Benin, now in Nigeria, in 1897. The spoils from that operation were eventually dispersed to dealers and institutions in the UK, Germany and the US. [See Arts Fuse interview with Barnaby Phillips. author of Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes.]

Africa’s Struggle for Its Art charts the prequel to current campaigns pressuring for the return of colonial plunder. It’s a small book – a dense 142 pages of text, plus forty pages of detailed footnotes — that stresses official European avoidance of accountability from 1960 to 1985. Its most concentrated focus is on Germany and the longstanding intransigence of German officials and museums. (Colonial plunder in US museums, a mostly-unexplored field, is a story waiting to be told.)

Today Germany is at the forefront of restitution, The Linden Museum in Stuttgart returned three objects to Namibia, the former German colony of Southwest Africa, in 2017. Germany plans to begin returning more works to Africa this year. Last year, France returned 26 objects to the country of Benin (formerly Dahomey).

Savoy, a French citizen now working in Germany, is the co-author of the Sarr-Savoy Report on the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage (2018), which the French government commissioned. President Emmanuel Macron pledged in 2017 that France would begin to return works from the vast number of sub-Saharan objects in French museums. Here are the French and English versions of that report. Savoy also collaborated on the French documentary film Restitution, watchable here on the website of WETA in Washington. The film lacks honest institutional perspectives on this debate (museum leaders tend to dodge the issue), but there’s eloquent testimony from African artists and historians.

Savoy stresses that African countries called for the restitution of looted objects as soon as they gained independence around 1960. “Nearly every conversation today about the restitution of cultural property in Africa happened forty years ago,” she insists in the measured tone that runs throughout her book. Some of those conversations began two decades earlier. Those countries would find that decolonization stopped at the European museums’ doors.

Nigeria and Ghana led the way in 1960, demanding the return of objects from their former colonizers. Congo (called Zaire since 1971) and Senegal joined them. In Zaire, President Mobutu Sese Seko, formerly Joseph-Désir Mobutu, was denounced as a corrupt CIA puppet and accused of ordering the 1961 murder of the progressive leader Patrice Lumumba. On issues such as mineral extraction, he avoided offending friends in Washington, Paris, and Brussels. Yet Mobutu spoke militantly about cultural heritage and demanded that European museums return pillaged objects.

In 1973, Mobutu told the UN General Assembly that “Hitler pillaged the Louvre during the Second World War, and took away the magnificent works of art which were there. When Liberation came, even before thinking of signing the armistice, France did everything in its power to recover its art objects, and that is quite right. That is why I would like to ask the General Assembly to adopt a resolution requesting the rich Powers which possess works of art of the poor countries to restore some of them so that we can teach our children and our grandchildren the history of their countries.”

Mobutu spoke of “some objects,” not all. But by then, the battle lines were clear. Museums in the UK, France, Belgium, Germany and elsewhere claimed to have been blindsided, and argued that they were preserving the objects that were acquired legally at the time. Some of the standard arguments took shape. The objects in question were in better hands in European museums, said museum directors, where they could be kept safe and be studied by trained personnel.

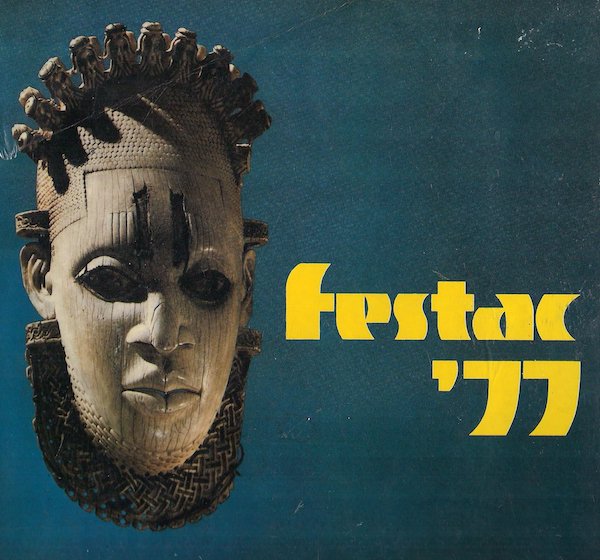

A poster for Festac ’77, an exhibition of African art and culture in Nigeria.

Loans to exhibitions in Africa were too risky, the countries were told. In 1977, the British Museum refused to loan an ivory mask of the 16th century Queen Idia, pillaged from Benin City, to Festac ’77, an exhibition of African art and culture in Nigeria. They offered to send a copy instead. (A confidential document revealed the museum’s fears: “The museum could reasonably anticipate that the Nigerians would not treat it with the care it demands, especially since the Nigerians would tend to think of it as their own property.”) Nigeria refused to accept the copy. In response, the country made the mask a symbol of that international event, eventually placing the image on a banknote.

Compiling and sharing inventories of works in museum collections would only encourage “covetousness,” museum directors argued. The fancied themselves as the victims of shrill ideologues. David Wilson, director of the British Museum, saw a two-sided threat — newly independent states were fiercely Marxist-Leninist (i.e., internationalist) and they were all too eager to exploit restitution claims for nationalist ends. “His comments recorded in the director’s office of the British Museum are marked by an almost unbearable institutional smugness,” Savoy writes.

Yet African governments persisted. With the appointment in 1974 of a Senegalese director-general of UNESCO, Amadou Mahtar M’Bow, the rallying cry for restitution from new governments became inescapable at international conferences. Besides having to deal with stalling from the museums, claims for restitution also faced structural problems. There was no legal ground for claiming objects stolen before treaties banned stealing them, and countries that did not exist before 1960 could not legally claim that they owned objects that were seized decades earlier.

Also, the British Museum’s charter blocked the return of items in its collections. The centralized French museum system did the same. In Belgium, however, which held many thousands of objects from Congo (renamed Zaire in 1971), objects were returned from the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren.

West Germany presented its own obstacles, as did East Germany, despite asserting that it had special fraternal ties with developing countries. In the German Federal Republic, which had no national ministry of culture, museums were a mix of city or state (Bundesland) institutions, or private foundations, or entities that operated independently. Many, Savoy notes, were run at the time by former Nazis who had no interest in cooperating with new African leaders. In 1978 the Berlin daily Die Welt ran the headline “The Ethnological Museum – A Den of Thieves.” Although they were pushed by the German government, which sought good ties with resource-rich new countries, many museum leaders delayed, often arguing that provenance research took time.

When snubbed, Africans and Asians found new arguments. One cultural official from Sri Lanka argued that objects looted from this country would be safer in Sri Lanka than in the center of Europe, in the line of fire between two nuclear powers. Those arguments became harder to make when China, India, and Pakistan got the bomb.

Europe also got a claimant from within in 1982 when Melina Mercouri, the actress and Greek minister of culture, demanded the return from the British Museum of the Elgin Marbles, “which for us, the Greeks, will always be the Parthenon Marbles.” That dispute still remains unresolved.

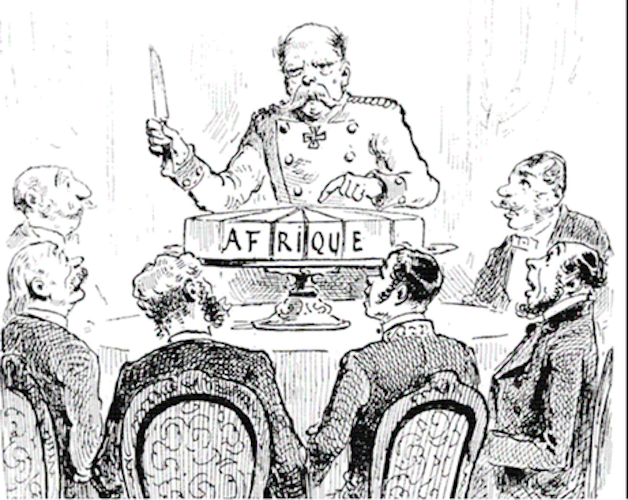

A cartoon from the late 19th century showing European leaders cutting up “Africa” in the form of a cake.

By 1978, the notion of restitution became so discredited among European museums that the word itself was avoided. One consequence: an organization formed to consider claims – or delay them — was given a cumbersome name that seemed to have been crafted for a farce on officialdom: “The Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to Its Country of Origin or its Restitution in Case of Illicit Appropriation,” or ICPRCP. The bureaucratic acronym shifted the focus away from the colonial pillaging which brought most of these objects to Europe. It put the spotlight on the more palatable issue of the illegal trade in objects.

Europe’s tactics succeeded in what amounted to a war of attrition. The once-noisy chorus of claims went quiet. Representatives of countries who found pillaged objects at the major auction houses were told that they could bid for them at public sales.

Africa’s Struggle for Its Art sometimes reads like a master’s thesis – too short for a doctoral dissertation, yet dutiful and probing in its presentation of evidence. In the book’s scrutiny of German institutions, all but one of which formed a wall of resistance, Savoy shows us how a campaign for restitution could be ignored, even with strong support from the press. It’s a little perplexing that she avoids comparisons with efforts to recover art that the Nazis looted, much of which was in the same museums.

Today, when renewed energy for restitution comes from a new generation in German museums (often led by women), the difference between then and now is the rise of public engagement. Disputes in the era that Savoy surveys happened in conference rooms.These current debates are taking place in the streets and inside museums, which are still conservative institutions that move slowly. As the media track that movement, Africa’s Struggle for Its Art risks being a book that is more talked about than it is read. That’s unfortunate. This is a history that few of us know. Bénédicte Savoy has given us an account that reminds us that the slow progress toward restitution in the ’60s and ’70s also seemed inevitable, until it wasn’t.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.