Book Review: “The Hawk’s Way” — Up-Close and Personal with Birds of Prey

By Ed Meek

Sy Montgomery raises the question of our relationship to the world and all its animals and nudges us toward the view that even predators deserve our support and admiration because of the value they bring to our planet.

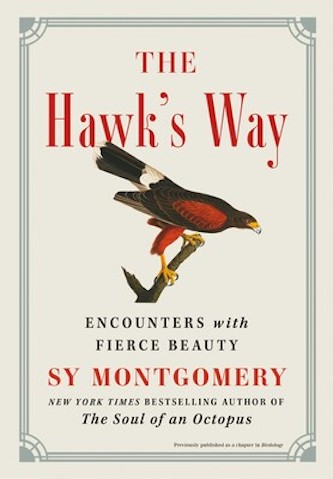

The Hawk’s Way: Fierce Encounters with Beauty by Sy Montgomery. Atria, 96 pages, $20.

Sy Montgomery is a naturalist who studies and writes about animals. She’s the author of 33 books about the subject written for both adults and children. In one of her recent volumes, How to Be a Good Creature (Arts Fuse review), Montgomery tells us about connections she made with an array of critters including dogs, a pig, a group of emus, and an octopus. She makes the argument that humans can establish relationships with these creatures and that our affections will be rewarded with both an appreciation of what is unique and valuable about their world and a reciprocated emotional bond. Many of us discovered this during the pandemic if we adopted a dog. Partly because dogs are often happy and affectionate, (long evolved as companions to humans), we learned that not only do we love our dogs, but they appear to love us back! People also of course rave about their attachment to horses or alpacas or even cats. Though cats are famous for their cool independence.

Sy Montgomery is a naturalist who studies and writes about animals. She’s the author of 33 books about the subject written for both adults and children. In one of her recent volumes, How to Be a Good Creature (Arts Fuse review), Montgomery tells us about connections she made with an array of critters including dogs, a pig, a group of emus, and an octopus. She makes the argument that humans can establish relationships with these creatures and that our affections will be rewarded with both an appreciation of what is unique and valuable about their world and a reciprocated emotional bond. Many of us discovered this during the pandemic if we adopted a dog. Partly because dogs are often happy and affectionate, (long evolved as companions to humans), we learned that not only do we love our dogs, but they appear to love us back! People also of course rave about their attachment to horses or alpacas or even cats. Though cats are famous for their cool independence.

In The Hawk’s Way, Sy Montgomery gets close and personal with birds of prey. She works with a falconer and learns that raptors challenge her views of the world of animals. They “hunt hard, and kill swiftly.”They are the descendants of dinosaurs and although humans have a long history of hunting with hawks, they remain wild and dangerous creatures who reluctantly allow humans to partner with them. “The junior partner,” trainer Nancy Cowan tells Montgomery.

In the eyes of a hawk Montgomery glimpses “a mind completely different” from ours. This is exactly what I saw watching lions, leopards and cheetahs hunt in Botswana. They were not concerned with us. They were completely focused on their prey. Montgomery notes that she is drawn to animals because “their sharpened senses give them a fuller experience of the world.” We learn that ironically, most hawks die in their first year in the natural world, but will survive for up to 20 years in captivity.

Although Montgomery loves the intense experience of tethering a hawk to a padded gloved hand and releasing it to hunt, she decides against apprenticing with Ms. Cowan. For one thing, Montgomery would be bringing a hawk to her farm where he would eat all of her chickens. Montgomery, who is an animal lover, finds herself in a compromised position; they hunt some of the animals she treasures. As the hawk’s partner, Montgomery feels almost like an accessory to a crime.

Our view of the animal world has been rapidly changing as scientists and observers record the elaborate lives of elephants who adopt baby pachyderms who’ve lost their parents to poachers, or whales who use complex songs to communicate as they circumnavigate the globe, or crows who time red lights to snatch roadkill, or octopi and dolphins who feel emotions through nerves in their skin. Not to mention the legendary Koko, the gorilla who learned a thousand words of sign language.

Philosophers Martha Nussbaum and Peter Singer, like Montgomery, make a case for animal rights. Not just for animals that are domesticated or similar to humans, but for all creatures. Novelist Doris Lessing pointed out that anyone arriving on earth from another planet would find our treatment of animals appalling, especially when it comes to eating them (the moral case for vegetarianism). Now, given the mounting problems due to our warming climate, we are being compelled to reassess what we eat: raising animals for food contributes to climate change. There is a growing movement to eat more vegetables and less meat because it is better for us and our world. At the same time, we are at the beginning of the development of manufactured replacements for animal food and products. Have you tried an impossible burger or almond milk?

In The Hawk’s Way, Montgomery raises the question of our relationship to the world and all its animals. She nudges us toward the view that even predators deserve our support and admiration because of the value they bring to our planet. In Glacier National Park I once watched bears fish for salmon, but the highlight of the venture was seeing eagles swoop from treetops to catch leaping salmon and fly them to the top of pines for a mid-day feast.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).