Book Review: The South – What Jim Crow Was and Wasn’t

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

We need to realize how important class is in order to understand how inequality can rise as Confederate monuments fall.

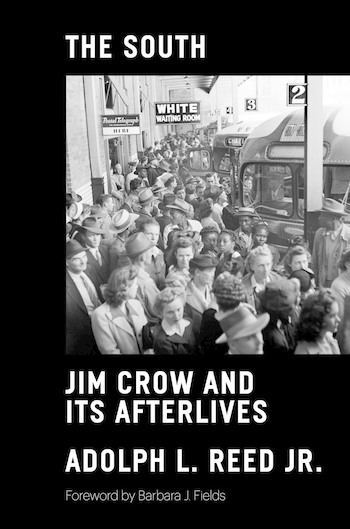

The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives by Adolph L. Reed. Verso, 176 pages, $14.97.

Adolph L. Reed Jr. has had a distinguished career as an academic, political scientist, and activist. In The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives he takes on a much more urgent role: an elder. The book is motivated, in part, by his perception that his “age cohort, those born in the first decade or so of the postwar baby boom, very soon will be the last living Americans with direct knowledge and recollections of the Jim Crow era.” Reed is dealing with the fate of anyone blessed/cursed to live long enough: to see their own lives become the subject of historiographical debates, political appropriations, and excessive analogizing. He has seen how the evaluations of this era are beginning to play out, and he felt that a precise intervention was necessary. This isn’t so much a memoir as it is a historical mediation. Drawing on his lived experiences growing up in the segregated South, Reed seeks to delineate exactly what Jim Crow was and wasn’t. He is speaking directly to the errors of today, which threaten to calcify the reality of the past into doctrinaire historical misunderstandings.

Adolph L. Reed Jr. has had a distinguished career as an academic, political scientist, and activist. In The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives he takes on a much more urgent role: an elder. The book is motivated, in part, by his perception that his “age cohort, those born in the first decade or so of the postwar baby boom, very soon will be the last living Americans with direct knowledge and recollections of the Jim Crow era.” Reed is dealing with the fate of anyone blessed/cursed to live long enough: to see their own lives become the subject of historiographical debates, political appropriations, and excessive analogizing. He has seen how the evaluations of this era are beginning to play out, and he felt that a precise intervention was necessary. This isn’t so much a memoir as it is a historical mediation. Drawing on his lived experiences growing up in the segregated South, Reed seeks to delineate exactly what Jim Crow was and wasn’t. He is speaking directly to the errors of today, which threaten to calcify the reality of the past into doctrinaire historical misunderstandings.

Reed maintains three crucial points. First, Jim Crow should not be taken as a less formative experience than slavery. In fact, it may be seen as more formative for Black America. Second, even though the system was extremely heterogeneous, it always existed to serve classism, regardless of the location, individual, or complexion involved. And finally, both today’s pessimists and optimists tragically miss the ways in which things have — and have not –changed. Celebrations of Black heritage and critical analyses of white supremacy both obfuscate what was the real power behind segregation – class. And that remains as vital as ever. Reed implies that what propels this partial vision is the desire to sever race from class. We need to realize how important class is in order to understand how inequality can rise as Confederate monuments fall. The truth behind “race” in the Jim Crow South was always class. The explanatory failures of “definitive taxonomies of racial classification” made in the early 20th century prove this elemental point, as do experiences of those like Reed, who lived during the time and never saw their world outside of its class-based infrastructure.

Reed asserts that “separate never was intended to be equal.” Yet this fact has been challenged from both sides throughout the decades, including by “race nationalists” who insist that efforts toward desegregation “reflected a demeaning presumption that black people needed proximity to whites for their validation.” Reed thinks that this argument may be rearing its head once more. Referring to legal historian Charles A. Lofgren, Reed reminds us that segregation “was not a major focal point for southern or black politics until it became an element of reassertion of planter and merchant class power after the defeat of Reconstruction and the Populist insurgency at the end of the nineteenth century.” The reassertion of that class power utilized the ideology of white supremacy, but it is worth noting that “the victorious ruling class didn’t impose the regime in most places until blacks (and many poor or working-class whites) had been taken out of the political equation by disenfranchising them.”

According to Reed, this disenfranchisement was the essential thrust of Jim Crow, and it “was enforced on whites as well as blacks.” The author notes that this fact is ignored (on the left and the right), the result of “the current attention to recuperating slavery as the essentially formative black American experience.” Instead, he insists that “it is Jim Crow—the regime of codified, rigorously, and unambiguously enforced racism and white supremacy—that has had the most immediate consequences for contemporary life and the connections between race and politics in the South and, less directly, the rest of the country.” That ‘separate but equal’, whether envisioned by a white supremacist or a Black nationalist, could have ever been implemented differently — as some sort of medicinal bridge between slavery and the present — is at best a chimera, at worst an apologia for oppression. There is no truth, argues Reed, in novelist Toni Morrison’s depictions of select Black communities during Jim Crow as “organic, self-contained societies.” Reed’s discrediting of treating the value of segregation/separation as an open question is refreshing. His attack on emphasizing slavery over Jim Crow is common sense rooted in firsthand knowledge:

The vast majority of black Americans, in the South and elsewhere, have shown themselves repeatedly to be much less interested in elaborate programs of separate development than in securing equal opportunity and justice in the here-and-now. Most people respond favorably to appeals to racial pride and solidarity, to be sure. And, within reasonable limits of convenience, cost, and quality, many will patronize black-owned businesses when they can. Even under segregation, however, that commitment was rarely dogmatic. Black people have not proven willing to commit themselves in substantial numbers to long-term projects that seem like pursuit of pie-in-the-sky, least of all, perhaps, when the principal benefit promised is being able to identify vicariously with others who would actually consume the dreamed-for pie.

Dreams of less arbitrarily-built bantustans, somehow less subject to white caprice, were always pure hokum. The diverse forms that Jim Crow took was one of its strengths. Reed’s personal accounts focus on his childhood in and around New Orleans. A fluid application of the sectional regime facilitated the incorporation of that city, with its Latin/Caribbean inflections and accompanying complex racial hierarchies, into the Jim Crow South. The picture we inherit from mainstream culture is that of a rigidly balkanized society. Yet some features of our landscape, such as the power of geographic separation, have been increasingly exaggerated since the end of segregation. Reed notes that throughout most of the Jim Crow era neighborhoods in the South were much more mixed than they became after World War II. Our understanding of segregation is false because it is based on erasing the profound adaptability to circumstances of the system and its participants. Yes, Jim Crow necessitated the same disenfranchisement everywhere, but the different ways in which that division was achieved in the name of a concept as vacuously open to interpretation as race belie the fact that a substantial homogeneity did exist. Perhaps it did not establish a perfect racial order, but it did maintain a desired class order. Even the phenomenon of “passing for white” saw numerous variations in practice within the standard binary racial framework.

Within its New Orleans variant, passant blanc, a Creole could be mistaken for a Sicilian. In a later example, Reed refers to the Haliwa tribe of Halifax and Warren counties (the name is a portmanteau of the two English names) in North Carolina. From 1953 to 1965, residents of those counties previously identified as Black sought to gain official state recognition as an Indian tribe. Unlike Virginia, North Carolina segregation laws allowed for separate schools for Indigenous peoples. Reed notes that most Black residents of the state at the time saw the effort as little more than an attempt by a particular group of Blacks to “pass” for something else and to thereby secure a separation from local Black schools. Whether this is true or not, it shows the wide range of responses and debate possible within what was nevertheless a concrete system with a common objective.

Colored entrance to the segregated Lake City railroad depot in 1941. Photo: Jack (John Gordon) Spottswood/ Florida Archives.

Nevertheless, Reed argues that no one “experienced any existential anxiety, not even a speed bump, in momentarily passing to get a box of beignets.” Such “instrumental passing,” at least, didn’t approach the agony of William Faulkner’s doomed Joe Christmas. Existentially tortured biracial souls may be found in that author’s white world, but the miasma of white supremacy didn’t occupy the minds of the conscious “passer.” Referring to Ralph Ellison’s fiction, Reed notes that “racial oppression did not occupy all of black people’s mental and social lives.” Instead, “Black southerners sought to create social and personal spaces in which they could express and realize themselves outside, or, as much as possible, within the narrow limits imposed by segregation.” If that meant passing in order to purchase a beignet, then so be it. The projection of existential dread was no doubt a byproduct of white supremacy; it bedeviled the minds of the segregationists rather than its primary targets. “Random individuals certainly still attempt to work out idiosyncratic issues bearing on race and identity by exchanging one racial identification for another,” Reed asserts, yet “instrumental passing was rendered obsolete by the demise of the segregationist order.” Yet it is essential to know that such a pathologization of race was not, as a rule, the experience of the intended victims of Jim Crow. It was a distinguishing characteristic, rather, of its perpetrators, those convinced by the ideology. The true purpose of that ideology – class oppression – never escaped those under its boot.

Reed’s final point is that “by definition, people who are oppressed know it.” Reed locates the denial of this commonsense principle in the ideas of radicals in the ’60s and’ 70s, who believed that “black Americans needed to be told that they were black.” Being “out of touch with the realities of popular black existence” continues today: once more we hear self-described leaders “self-righteously announce the obvious and offer only unthinkably remote, millennial routes to justice like ‘revolution’ or ‘unity’ (or now, reparations).” In her introduction to this volume, Barbara J. Fields writes that “Soi-disant progressives are more likely these days to invoke ‘white supremacy’ than are troglodyte racists.” The useless restatement of the obvious remains in force: if historical white supremacy, as it has previously been codified and today felt in its afterlife, is still all there is to be said about today’s concerns, then the millenarian horizon proposed will be infinitely distant.

To make his case,Reed returns to New Orleans and its removal of Confederate monuments under Mayor Mitch Landrieu. “Both the processes of neoliberalization and racial integration of the city’s governing elite accelerated in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,” concludes Reed. He goes on to insist that while New Orleans’ leaders “acted courageously and progressively in ridding the city of those monuments to a loathsome past, the new regime that removal celebrates […] rests on commitments to policies that intensify economic inequality on a scale that makes New Orleans one of the most unequal cities in the United States.”

Thus the irony of how the local government is re-branding itself. It simultaneously “contributes to this deepening inequality through such means as cuts to the public sector, privatization of public goods and services, and support of upward redistribution through shifting public resources from service provision to subsidy for private, rent-intensifying redevelopment (commonly but too ambiguously called ‘gentrification’).” The net effect of these measures “do not target blacks as blacks.” The strained attempts to paint them as a “new Jim Crow” suffers from delusions about the past and the present. It illustrates the lack of commitment to working-class issues on the part of those undertaking cosmetic measures in the name of inclusion, multiculturalism, or (symbolic) racial justice. Reed highlights the ways in which both optimists and pessimists are united in their common acceptance of a certain “cover story.”

The white supremacy that today’s officialdom is celebrated for leaving behind was, after all, “as much a cover story as a concrete program, even though it was by far the most immediately visible and consequential aspect of the segregationist order.” What are the most immediately visible and consequential aspects of attempts at remediation? “Civil rights tourism has become a multibillion-dollar niche within the historical/heritage tourism industry” while white supremacy is again evoked as the “explanation” for economic inequality. “What seem to be vestiges of the Jim Crow world in a sense are just that. But passage of the old order’s segregationist trappings throws into relief the deeper reality that what appeared and was experienced as racial hierarchy was also class hierarchy.” If we can take that lesson away from the past, as Reed and his contemporaries lived it, then maybe we can stay on the straight and narrow as we push forward into a future that, as Jim Crow fades, spotlights economic inequality.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: Adolph L. Reed, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Jim Crow, Racism, The South

Mr. Jewell, thank you very much for that incredibly thoughtful and empathetic review. More than anyone, you’ve sensed what I consider to be the book’s point and central arguments, as well as my perspective in writing it.

Adolph Reed, Jr.

Thank you very much, Dr. Reed! It is always enlightening to read your words. I hope you and your loved ones are all doing well and keeping safe in these times.

Best,

JRJ