Jazz Album Review: Manel Fortià Trio’s “Despertar” — Intelligently Lyrical

By Michael Ullman

Manel Fortià’s album of his Spanish-tinged compositions is meant to wake us up to what the bassist can do.

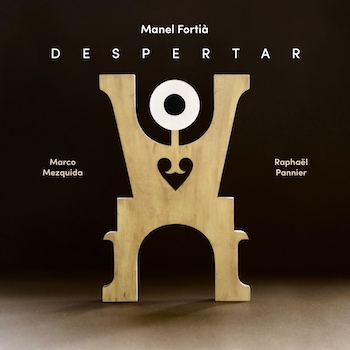

Manel Fortià Trio, Despertar (Segeli Microscopi)

Despertar, which the album’s leader translates as meaning something like “awakening,” is Barcelona-born Manel Fortià’s first collection of his own compositions with his European trio, which consists of the Spanish pianist Marco Mezquida and the French drummer Raphaël Pannier. Recorded in Spain, the recording’s subject is New York, or rather the bassist’s experiences in the city. “This album is very important to me because it reflects one of the most transcendent moments in my artistic life. I feel that living in NYC changed me tremendously and I grew a lot there.” The set and its leader come highly recommended by Dave Liebman and Arturo O’Farrill. Fortià has been a sideman to both, as well as to such prominent musicians as Ari Hoenig and Chris Cheek.

Despertar, which the album’s leader translates as meaning something like “awakening,” is Barcelona-born Manel Fortià’s first collection of his own compositions with his European trio, which consists of the Spanish pianist Marco Mezquida and the French drummer Raphaël Pannier. Recorded in Spain, the recording’s subject is New York, or rather the bassist’s experiences in the city. “This album is very important to me because it reflects one of the most transcendent moments in my artistic life. I feel that living in NYC changed me tremendously and I grew a lot there.” The set and its leader come highly recommended by Dave Liebman and Arturo O’Farrill. Fortià has been a sideman to both, as well as to such prominent musicians as Ari Hoenig and Chris Cheek.

Despertar is a suite and it takes the form of a kind of journey in reverse. The trip begins with “Dormir,” which is about sleep; it ends with the title cut, “Despertar.” To me, “Dormir” sounds breathtakingly lyrical rather than sleepy. It opens with the bassist playing solo over the just barely audible patter of Pannier’s brushes. Here Fortià is wearing his influences on his sleeve. That beautiful, carefully paced opening solo quotes Charlie Haden’s opening solo on Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman.” Fortià’s big, vibrant bass sound is captured accurately. There’s just the right amount of resonance — few recorded basses sound this warm and yet precise. On this opening number, Mezquida enters quietly, playing (discreetly) the single notes of Fortià’s lovely, pastoral melody. After a swelling passage, the pianist is left to rehearse the melody by himself. The trio is clearly sensitive to each other: our attention shifts seamlessly from one instrument to another.

What follows next is amusing. “Circular” is subtitled “to JFK AirTrain.” It’s a lively, dance-like piece, whereas the restless “Saudades (To Astoria)” finds the pianist playing a constant left-hand pattern even as he solos with anxious tremolos in a gradual crescendo. The tension in this number rises until the end, when Mezquida suddenly retreats, playing the melody quietly so that we can hear the bassist, who has heretofore been in the background. The two play the melody in unison and the piece ends, happily, I think. “Espiritual” is a tribute to gospel music in 6/8 that begins with a thumping drum: maybe New Orleans brass band music is also an influence here. Remarkably, Mezquida manages to evoke gospel without falling into clichés. The somber “El Dia Después” is dedicated to a famous pedestrian street in Barcelona: it contains one of Fortià’s most elegant solos. Charles Mingus denounced bassists who sacrificed sound in order to play rapidly; I imagine that he’d have approved of this Spanish bassist. Fortià isn’t given to guitar-like flourishes. He’s more Charlie Haden than Scott LaFaro: every note is played so distinctly it assumes dramatic importance.

After the Spanish interlude of “El Dia Después,” the album goes back to Manhattan with “Crescente,” which is played in honor of, of all places, Grand Central Station. This track, like much of the album, will strike listeners as intelligently lyrical, its melodies appealing yet also distinctive. “Simple,” however, is a weirdly jumpy piece. The pianist opens at something like double time. Dedicated to Jackson Heights, it settles down when the bassist solos, only to heat up again. It’s hard to imagine what is simple about Jackson Heights, but this composition leads to the title cut. Having had our sleep and various travel experiences, we arrive at the awakening with the gently evocative “Despertar.” The track provides a satisfying close to this well-played and recorded set of originals. Although Fortià has appeared on about 50 albums as sideman and co-leader, readers may not have heard of him. (Bassists have a way of remaining anonymous.) This album of his Spanish-tinged compositions is meant to wake us up to what he can do.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.