Book Review: Thomas Mann in America

By Will Aitken

In the US, Thomas Mann tacitly proposed himself as an almost messianic figure, stately, dramatic, and wrathful at once, striding forth to represent German culture in exile and, increasingly, free Germany itself.

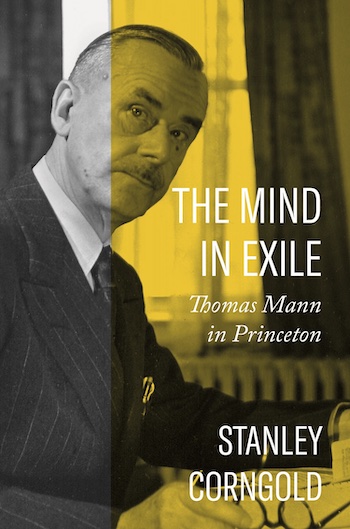

The Mind in Exile: Thomas Mann in Princeton by Stanley Corngold. Princeton University Press, 258 pp.

Considering Goethe’s dictum, “Unconditional activity in the end bankrupts you,” Thomas Mann (1875-1955) asked himself, in exile in 1949 in Princeton, NJ, “But how does one begin to be inactive?”

The great oak of 20th-century German literature – he won the Nobel Prize in 1929 — the author of Death in Venice, Buddenbrooks, and The Magic Mountain was deracinated when Nazi Germany stripped him of his citizenship in 1936. Three years later saw him hastily transplanted to Princeton University, where he received an honorary professorship.

Such an abrupt imposition of emigré status might have destroyed or at least given pause to a less protean talent, but during his two-and-a-half years at Princeton, Mann finished one novel, Lotte in Weimar, and made steady progress on the fourth volume of his Joseph and His Brothers tetralogy; he also completed a novella — The Transposed Heads — and delivered seven on-campus lectures, their subjects ranging from Goethe to Wagner to Freud.

From early on Mann’s output had included political essays as well as fiction, attaining fever pitch during his brief time in academe (he later confessed to feeling intimidated there, having never finished high school). He wrote essays, speeches, and manifestos and traveled the US as a public intellectual, holding forth at town halls, community groups, and colleges. By this point he was crafting propaganda of the highest order, determined to cajole the US into joining England in the war against Hitler.

In autumn 1940 Mann also began broadcasting, in German, directly to Germany, the first of 61 radio messages that he called “rocks thrown into Hitler’s window,” prompting the Führer to denounce him in a Munich beer hall speech.

Stanley Corngold, author of The Mind in Exile and Princeton professor emeritus in German and comparative literature, commends these airwave lectures for their “sacred furor.” At the time, US theologian Reinhold Niebuhr considered them naïve and deficient in their grasp of realpolitik. He accused Mann of striking similar barbarous notes to Goebbels when he wished that, following Germany’s eventual defeat, “the vindictiveness of the whole world will break loose” upon his Heimat. Mann also repeatedly and heartlessly urged Germans to rise up against their fiendish master — “There will never be enough terror at work to suppress a people’s decision to be free” — a sentence of sure death.

The Mann we meet in these pages makes a curious admixture for those who know only his fiction. True, his style is as orotund as ever, his diction choice, imagery, and metaphors as exact and pungent. Audiences in the thousands turned out to gaze upon this colossus of world literature who had attained almost statesmanlike stature. How much they actually comprehended, given his elaborate rhetoric, labyrinthine argumentation, and sumptuous irony, is another matter. There was also the problem of his heavily accented and frequently garbled English. A colleague suggested Mann may as well have delivered his speeches in German and thus heightened their intelligibility.

Mann tacitly proposed himself as an almost messianic figure, stately, dramatic, and wrathful at once, striding forth to represent German culture in exile and, increasingly, free Germany itself. The urgency of his quest was palpable as he stood before his auditors, a traumatized man, betrayed by his own nation, his own people, “the smell of the fire of world history in one’s nostrils, and in one’s ears the SOS calls of the dying.”

He was out not only to defeat his errant homeland and severely punish it for its horrific misdeeds. His transcendental longings prompted him to call for a new postwar order based on socialism, his own hybrid conception of Christianity (he was at best a liberal if militant humanist), democratic principles, and a more equitable and pacifistic world community.

Living in the US and soon to be a naturalized citizen, he nevertheless recognized early in his stay that, as Corngold tells us, “Fascism was as rampant both outside and inside” his adoptive nation. “I don’t believe in this country,” he wrote presciently in 1940, “and have not for a long time. It is undermined, paralyzed and ready for a fall like the rest of so-called civilization. It may not offer us [i.e., Mann and his large family] security much longer.”

Capable of thundering jeremiads against allies and enemies alike, he denounced the Munich Pact of 1938, which allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland, buying “peace in our time,” but not much of either. In helping to concoct the Pact, he charged, England and France essentially “saved Fascism.” He denounced anti-Semitism everywhere he went and “named by name the Nazi extermination of the Jewish people of Eastern Europe” at a time when American anti-Semitism was as homegrown and vocal as Henry Ford or Charles Lindbergh.

His earliest speeches writhe with coruscating irony, particularly one called, variously, “A Brother,” “That Man Is My Brother” and “That Man – My Brother – Is Hitler,” in which he purports to find similarities between himself and his “unpleasant and mortifying brother.” They were both German, after all, and both artists, though Mann a phenomenally successful one and Hitler an abject failure who “dragged the artistic impulse into the realms of darkness.”

As his attacks gather momentum and urgency, his arguments refine themselves and become more deeply grounded. Many at the time saw Hitler as an aberration in the history of a great European nation: Mann went to savage lengths to show him as the logical culmination of German thought. Criticizing Germany for always having favored their Kultur over civilization, their mythos over their reality, he pointed out that “the unhappy course of German history … is very much caught up with that unpolitical cast of the bourgeois mind, and with its anti-democratic habit of looking down the nose from its intellectual and cultural height at the sphere of the political and social class.”

He came from this class and knew too well its “conservative radicalism” and its “profound and foolhardy indifference to freedom.” At the height of the First World War he had written a notorious essay called “Thoughts in War,” in which he justified the Great War, Corngold notes, “on behalf of German culture against the corrupting values of … “democracy, politics, newspapers.” But by 1922 he had declared his loyalty to the parliamentary democracy of the new Weimar Republic.

Profoundly ashamed of his earlier prowar fulminations, Mann eventually detected authoritarian and profoundly antidemocratic attitudes among Germany’s greatest thinkers that paved the way to Hitler’s ascendancy. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) was “a revolutionary reactionary who thrust reason from her throne and made her a creature and tool of the ‘Will’.” Worse, Friedrich Neitzsche (1844-1900) “created a rapturously anti-human doctrine whose leading concept of power, instinct, dynamism, supermanhood, naïve cruelty … represent the amoral triumphant life force.” Only Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) escaped Mann’s wrath, with his beehive theory of the state “as the culminating point of all human striving,” a position Schopenhauer dismissed as “the grossest philistinism.”

Thomas Mann — he was hounded out of the US by the combined forces of the FBI (his file ran to 99 pages) and the House Un-American Activities Committee at the start of the Cold War. Photo: WikiCommon

Almost inevitably, in explicating and paraphrasing so many discourses on roughly the same bellicose themes, there’s a fair amount of repetition in Corngold’s own argumentation, as if he’s never met a tautology he didn’t like. The momentum of the forced march through the material all too vividly recalls the tedium of the lecture hall and is undercut by tangent discussions of the perniciousness of woke youth and rather random speculations — for instance, a bewildering aside on cultural anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, whom Mann had not read “but could have read in Switzerland … in the year of his death in 1955.” If my grandmother had wheels she could have been a bike.

But Corngold’s commitment to Mann’s towering complexity never falters, even when he alludes to the great man’s flaws that more partisan scholars might have passed over in silence. Living on such an Olympian plain, Mann had little idea of what life was like for ordinary people: his wealth, endless privilege, and insatiable ego allowed him to pontificate from a very great height. It’s curious, though, that Corngold doesn’t mention Mann’s bisexuality, but this could be in reaction to The Magician, Colm Toibin’s 2021 semi-steamy biographical novel about Mann, which came close to reducing the man to his unfulfilled sexual appetites.

As he had foreseen, Mann was hounded out of his new nation by the combined forces of the FBI (his file ran to 99 pages) and the House Un-American Activities Committee at the start of the Cold War. Like so many others before him, when the USSR was an ally in the war against Hitler, Mann wrote about it as an ally. Never a communist, but never anticommunist, he called himself a noncommunist and when called to testify at HUAC’s hearings into the communist infiltration of Hollywood announced, “I have the honor to expose myself as a hostile witness.” He went on to compare the committee’s activities to Fascism’s rise in Germany. “I had to get to be 75 years old,” he observed in 1951, “and live in a foreign country that has become home to me just to see myself publicly called a liar, by burners of witches.”

Thomas Mann and his family decamped to Switzerland in 1952. He died there three years later, at the age of 80.

Will Aitken has written four novels, The Swells, (2022), Realia, (2000), A Visit Home, (1993) and Terre Haute (1989), as well as two nonfiction books, Antigone Undone: Juliette Binoche, Anne Carson, Ivo van Hove and the Art of Resistance (2015), and Death in Venice: A Queer Film Classic (2011). He lives in Montreal.

Thanks for a very interesting essay on a part of Mann’s life few of us know when, aiming his barbs at Hitler, he had no time for Tadzio.

my pleasure mr peary

Yes, a fairly good essay, in which all the substance is simply taken from Corngold’s book,

–if you omit the reviewer’s private obsessions. There’s the giggling asininity of Aitken’s attempt to mock a sentence of Corngold’s that has the plain intent of establishing a date. The lives and books of Mann and Levi-Strauss, both of whom are quoted about contemporary barbarism, overlapped in 1955. Aitkens writes that Corngold could have discussed Mann’s bisexuality, but did not, and that “could be in reaction to The Magician, Colm Toibin’s 2021 semi-steamy biographical novel about Mann.” And if my grandmother had not reacted indifferently to wheels, she could have been a bicycle. Corngold’s alleged comment on the “perniciousness of woke youth” is also in the reviewer’s head. Finally, Aitken misquotes the book that has given him his essay. Corngold writes that ca. 1940, “Fascism was rampant both outside and inside America.” True. Aitkens, allegedly quoting Corngold, writes: “Fascism was as rampant ‘both outside and inside’ his adoptive nation.” False. A small but meaningful difference? Aitkens might do well to spend a few more hours in the academic “lecture halls” that he finds so tedious.

–Adam Berenson