Opera Album Review: The Boston Early Music Festival — One of the Best Recordings Ever of a Baroque Opera

By Ralph P. Locke

The Boston Early Music Festival returns in person — and in a world-premiere recording of a German Baroque opera.

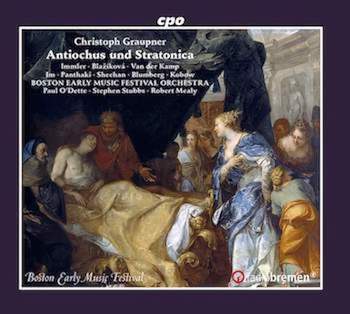

Antiochus and Stratonica by Christoph Graupner

Hana Blažiková (Stratonica), Sunhae Im (Mirtenia), Sherezade Panthaki (Ellenia), Aaron Sheehan (Demetrius), Jan Kobow (Negrodorus), Christian Immler (Antiochus), Harry van der Kamp (Seleucus).

Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra, musical direction by Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs.

CPO 555369 [3 CDs] 3 hours 43 minutes

Click here to purchase or to listen to each track. Also available on Spotify and other streaming services.

The Boston Early Music Festival has rightly been called, by the BBC, “arguably the most important and influential Early Music event in the world.” BEMF has recently announced its return to live performance, with a concert on April 29, to be made available virtually May 13-27. Future events include a major festival in October 2023, featuring productions of two operas created in part by women (one by Francesca Caccini, a work whose 2018 BEMF recording won a Grammy; the other by Henri Desmarest with a libretto by Louise-Geneviève Gillot de Saintonge).

The Boston Early Music Festival has rightly been called, by the BBC, “arguably the most important and influential Early Music event in the world.” BEMF has recently announced its return to live performance, with a concert on April 29, to be made available virtually May 13-27. Future events include a major festival in October 2023, featuring productions of two operas created in part by women (one by Francesca Caccini, a work whose 2018 BEMF recording won a Grammy; the other by Henri Desmarest with a libretto by Louise-Geneviève Gillot de Saintonge).

What Boston music-lovers can expect is clear from BEMF’s most recent recording: an astoundingly wonderful rendering, and the first recording ever, of Antiochus und Stratonica, a German Baroque opera by Christoph Graupner (1683-1760).

Don’t confuse this composer with Johann Christian Gottlieb Graupner, who was born a little later and came to America, where he co-founded Boston’s renowned Handel and Haydn Society.

The present Graupner, Christoph, was widely respected in his day, so much so that he was offered the job of cantor in Leipzig. The position eventually went to Bach, after Graupner worked out a better financial deal with his longtime employer, the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt.

When Graupner died, his music remained property of the Darmstadt court. This prevented his heirs from publishing the works but also ensured that the works would survive intact. They are only now being discovered and performed. My impression, on the basis of Antiochus und Stratonica, is that they are as accomplished as, say, those of Telemann, which to my mind is saying a lot.

Antiochus und Stratonica (1708) has a subtitle: “Lovesick.” More precisely, it’s printed above the main title in the original published libretto, and in two languages: “L’Amore ammaloto” / “Die kranckende Liebe.” There are plenty of lovesick people in this engaging work. The magic-wielding Persian princess Mirtenia is obsessed with the imperial treasurer Demetrius. (We are in and around the Syrian city of Damascus in vaguely ancient days.) The comic character Negrodorus hopes that he might pair up with Demetrius’s wife Ellenia. Antiochus, son of the Assyrian king Seleucus (by his first wife), is besotted with his stepmother Stratonica. Antiochus faints at one point, and at another seems to be dying. The Macedonian physician and ambassador Erasistratus (also known as Hesichius) feels his pulse and figures out that he is lovesick.

Seleucus, in a typically Baroque-era gesture of lordly generosity, frees his wife Stratonica to marry her beloved Antiochus. Grateful to Erasistratus for diagnosing his son’s condition, Seleucus makes the Macedonian a prince and pairs him up with the Persian magician-princess Mirtenia. Demetrius and Ellennia, already husband and wife, are reunited. Seleucus ends up alone but presumably feeling virtuous, and the ever-joking (and comically fearful, etc.) Negrodorus comments that he, too, would like to become a court physician, now that he has learned how to do a diagnosis (well, at least of lovesickness).

There are of course more complications than this. At one moment Ellenia pulls a dagger on her rival, Mirtenia. The booklet includes a fascinating preface by the librettist, Barthold Feind, that lays out major differences between his treatment of the legendary characters and that of several previous librettists. Helpful footnotes identify individuals mentioned in Feind’s preface and allusions in the libretto itself. (The “beautiful monster,” as one might not guess, is the mythological Ariadne.)

Typically for operas written for the Gänsemarkt (Goose Market) theater in Hamburg (including ones by Reinhold Keiser — mostly lost today — and by the young Handel), the arias and duets are immensely varied. Many numbers go through the stanza or two of text rather quickly and then stop. But some arias are in full da capo form; a few of these have Italian texts rather than German ones. Toward the end of Act 2, Antiochus gets an astounding nine-minute mad scene alternating accompagnato recitative and more strictly aria-like passages. A similar structure (eight minutes long) occurs, likewise for Antiochus, in Act 1, beginning with an aria about how he is feeling as if he were lost in a maze.

Some duets begin with brief interchanges between the two characters and then conclude with passages of more extended simultaneous singing — rather like what Mozart would do 79 years later in the “La ci darem la mano” duet (in Don Giovanni). Or one character briefly interrupts another’s aria; for example, Demetrius comments on the sudden disappearance of Mirtenia, after his wife Ellenia — not knowing that he is nearby — has begun a soliloquy aria stating that she will remain faithful to him.

Many arias and larger numbers contain a prominent solo part for one or two instruments, such as a pair of oboes or, in two arias and quite unusually, a sola viola. In Antiochus’s “lost in a maze” aria, four obbligato instruments interweave in a pointedly disconcerting fashion.

The performers outfit the continuo group very colorfully, with guitar, two theorbos, Baroque harp, harpsichord, and, occasionally, a gentle organ. There’s a gorgeous trio in Act 2 for Demetrius, his wife Ellenia, and the bewitching Mirtenia. The numerous dance movements are lost, so the performers have supplied apt and colorful substitutes from Graupner’s many orchestral dance-suites.

Boston Early Music Festival singers performing Antiochus and Stratonica.

The singers are nearly all a delight to listen to, and they have been superbly coached by stage director Gilbert Blin in delivery of the text. But I would have preferred hearing mature singers, not piping youngsters, in the roles of Demetrius and Ellenia’s children. They do sing accurately, though, and they appear only briefly.

Everybody’s German pronunciation and word-emphasis is at least quite good and often exquisitely right. There are frequent passages in which a chorus replies to a character, which increases the musical variety and sometimes leads to large scene-complexes (e.g., Act 1, scene 6), roughly analogous to ones in Lully and Rameau operas (or Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas). By contrast, Italian-language operas by Handel, Vivaldi, Hasse, or Vinci tend to consist primarily of a string of da capo arias (though these are usually well suited to the specific character and situation).

I was happy to re-encounter Jan Kobow (whom I praised in Meyerbeer’s comic opera Alimelek, as the goofy Negrodorus and Sherazade Panthaki (whom I heard here in Washington, DC, in Opera Lafayette’s semistaged performance of parts of Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes) as Demetrius’s faithful wife Ellenia. Harry van der Kamp is, by this point in his career, slightly unsteady as King Seleucus, but this feels believable, as the character is old enough to have a grown son. Jesse Blumberg (in the role of Hesichius/Erasistratus) does not always attack pitches cleanly, a problem that I did not notice four years earlier on a CD of songs of Louis Durey. Best of all are Christian Immler — a much-recorded Lieder and oratorio singer — as Prince Antiochus, Hana Blažiková as the stepmother whom he loves, and Sunhae Im as the sorceress Mirtenia, each blending vocal glamor and interpretive insight in masterful manner.

The orchestral contribution offers constant pleasure: tempos are generally brisk but not frantic and are altered to match this or that expressive point from a singer.

The Boston Early Music Festival originally planned to stage the work over a decade ago, and had even published an edition of the score in anticipation, but was prevented by that year’s Great Recession. This recording was made, not in Boston, but in Bremen (Germany), in January and February 2020, just before most musical activities shut down for the pandemic. The result is surely one of the best recordings of any Baroque opera ever made, and all the more special for being of a German opera, whereas most such recordings are of French or Italian works (plus, of cour,se Purcell). I shall treasure it — and look for more Graupner to listen to. Gramophone magazine is right: “nothing short of revelatory.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Antiochus and Stratonica, Christoph Graupner, Paul O'Dette, Ralph Locke, Stephen Stubbs