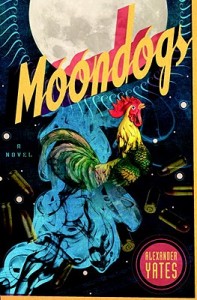

Book Review: Of “Moondogs” and Evil Green Roosters

Moondogs comes of as an entirely fun jaunt through a foreign land that nevertheless hoped to do a bit more. Still, the promise of Alexander Yates’s first novel more than justifies picking up his second, even if it lacks villains, superheroes, and evil green roosters.

Moondogs by Alexander Yates. Doubleday, 352 pages, $25.95.

Moondogs by Alexander Yates. Doubleday, 352 pages, $25.95.

By Tommy Wallach

Lying somewhere on the border between the literary sacred cow known as “magical realism” and the genre standby called “fantasy” comes Alexander Yates’s debut novel, Moondogs. Like an episode of Heroes written by Graham Greene and Elmore Leonard, Moondogs is a bit like a decent light beer: it may lack heft, but not only does it still get you drunk, it won’t give you a spare tire. Put more prosaically, the novel may be a little pulpy but in the entertaining, action-packed, “smashed to a pulp” kind of way.

Raised in Haiti, Mexico, and Bolivia, educated in the Philipines, and furnished with an MFA from good old Syracuse, Yates is perfectly suited to write a novel set in the mean streets of Manila, and his evocation of that place is believable enough (Full Disclosure: I have never been to the Philippines, and for the first few pages of the novel, I thought Tagalog was a kind of Girl Scout cookie). The book opens on a trio of “villains,” made up of one small, dumb guy, one large, dumb guy, and an evil, green rooster named Kelog (think Corn Flakes). On the very first page, we learn that the villains have just kidnapped Howard Bridgewater, a shady, American businessman, setting the action of the novel in motion.

Moondogs has a number of narrators, but the many plotlines quickly converge. Benicio, Howard’s son, has just returned to the Philippines to reconnect with his estranged father, only to find he’s been abducted. Monique is an American Services employee assigned to do PR for the rescue attempt. She is having an affair with Reynaldo Ocampo, a supercop who has inspired a series of over-the-top action films called Ocampo Justice. Reynaldo leads a covert ops team, Task Force Kapow, each member of which is a bruho, which translates roughly to “sorcerer.” A fourth protagonist, Efrem, joins Kapow when Reynaldo discovers the boy’s ability to shoot anyone and anything from any distance, even if they’re on the other side of the world. As Efrem sees it, “The gift was nothing to be afraid of. The angel of death was still an angel.”

Though all of these characters get their time in the spotlight, Benicio is the novel’s polestar and also Yates’s most well-developed character. Benicio has been alienated from Howard ever since he caught him cheating on his wife (Benicio’s mother) with a diving instructor for whom Benicio himself had expressed a schoolboy crush. They are reunited after Benicio’s mother dies. At the funeral Benicio tells him, “I haven’t forgiven you yet, but I will.” But once his father has been kidnapped, Benicio tortures himself with the idea that he could have reconciled with Howard already.

Benicio comes to the Philippines both to bond with his father and to get some perspective on his relationship, which is highly dysfunctional. He flirts with temptation, but the arc of all of Moondogs’ characters is upwards, towards moral, emotional, and even financial betterment. Monique will eventually end her affair. Benicio will find some more healthy way to love. Efrem, the super-sniper, will earn the title of superhero and use his power only for good.

In this way, Moondogs is an unabashedly simplistic novel, in spite of the fact that it has some things to say about relationships both political and personal. Imagine a version of The Quiet American in which Pyle was the narrator instead of Fowler. Most of the major characters in Yates’s book are Americans, and though the plot is set in the present day, an anachronistic (though far from irrelevant) anti-imperialist sentiment runs through it. When Benicio tries to blame Manila for corrupting his father, he gets a full dressing down from one of the few locals that Yates allows a voice:

“Manila didn’t make your father shitty. People are who they can afford to be. When your father was here he could afford to be Mr. Playboy. Maybe at home he could afford less. That doesn’t mean he was different. And it’s the same with you—you can afford to be Mr. Goddamn Generous. You can afford to spend a fuckload on peace-of-mind, because you’ve got a fuckload to spare. But don’t tell me, or yourself, that leaving will make you better.”

The darker elements of the plot—Howard’s torture at the hands of his kidnappers, the violence endemic to the region, even Benicio and Monique’s relationship troubles—clash a bit with the many madcap sideplots. There is Kelog the evil rooster, who seems to have some kind of magical intelligence that is never remotely explained or justified. Then there are the many bruhos of Task Force Kapow. One member has the power to transform into animals. Another has the unlucky fate of being the only person injured on any given mission. As a result, his entire body is one giant scar.

The problem with all this magical mumbo-jumbo is that it’s mostly extraneous, which is why I hesitate to call the novel magical realism. Sure, Moondogs wouldn’t be nearly as fun without the superhero stuff, but it might have allowed Yates to invest more deeply in the emotional lives of his characters, most of whom are well-limned and believable. Unfortunately, it’s hard to take seriously the personal difficulties of a woman who occasionally reaches down into the earth and causes volcanoes to erupt. Moondogs is the rare book that I actually wish had been a bit longer, as the collage structure gives us little more than half a dozen chapters with each character. Often the more subdued sections, such as a lovely and subtle scene in which Benicio goes diving with two native Philippinos, are undercut by the souped-up action scenes and bathetic comic vignettes.

This modern style of blending the real and the unreal, which remains unnamed as far as I know, has been put to its best use by Jonathan Lethem, who has always enjoyed popping a bit of the old sci-fi razzle-dazzle into his otherwise highly literary and realist novels (see Chronic City, The Fortress of Solitude, and even his early science fiction work). Yates is new to the game, and I can only imagine that if he continues in this genre, he’ll find better ways to integrate the naturalistic and the supernatural in order to form a coherent whole. In this book, the magic feels tacked on, whereas in Lethem’s novels (or Marquez’s, for that matter), it feels like an organic extension of the fundamental mystery of life and love that all literature attempts to describe.

I can’t help but view Moondogs as juvenilia—an entirely fun jaunt through a foreign land that nevertheless hoped to do a bit more. Still, I look forward to seeing what Yates comes up with next. The promise of his first novel more than justifies picking up his second, even if it lacks villains, superheroes, and evil, green roosters.