Author Reconsideration: The A, B, and C of Sue Grafton

By Daniel Gewertz

The conveniently tidy endings do turn killing into an entertainment. They also allow us to briefly believe in redemption. And that is not the vainest of hopes.

Some 77 years ago, critic Edmund Wilson caused a stir with a New Yorker essay dismissing the whole genre of mystery with high-handed hostility. The idea of an elitist critic writing anything about popular genre fiction was a rarity in the 1940s, a pre-television era when “serious” critics avoided pop culture as assiduously as writers on haute cuisine dodged neighborhood bar & grills. The three brows — high, middle, and low — rarely met. Wilson’s contempt wouldn’t have shocked his most regular readers: America’s foremost literary critic had already sprinkled scorn upon genre fiction, calling Lord of the Rings “juvenile trash” and H.P. Lovecraft a hack. That a few dozen of Wilson’s readers had the temerity to admit being mystery lovers seemed to annoy the imperious critic no end. In 1945, America was a war-weary nation in concerted need of escapist entertainment. Wilson, meanwhile, quipped that one answer to the wartime paper shortage might be to legally deny mystery publishers the privileges of the printing press.

Some 77 years ago, critic Edmund Wilson caused a stir with a New Yorker essay dismissing the whole genre of mystery with high-handed hostility. The idea of an elitist critic writing anything about popular genre fiction was a rarity in the 1940s, a pre-television era when “serious” critics avoided pop culture as assiduously as writers on haute cuisine dodged neighborhood bar & grills. The three brows — high, middle, and low — rarely met. Wilson’s contempt wouldn’t have shocked his most regular readers: America’s foremost literary critic had already sprinkled scorn upon genre fiction, calling Lord of the Rings “juvenile trash” and H.P. Lovecraft a hack. That a few dozen of Wilson’s readers had the temerity to admit being mystery lovers seemed to annoy the imperious critic no end. In 1945, America was a war-weary nation in concerted need of escapist entertainment. Wilson, meanwhile, quipped that one answer to the wartime paper shortage might be to legally deny mystery publishers the privileges of the printing press.

The sly name of his lordly essay — Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd? — was a play on the old Agatha Christie title.

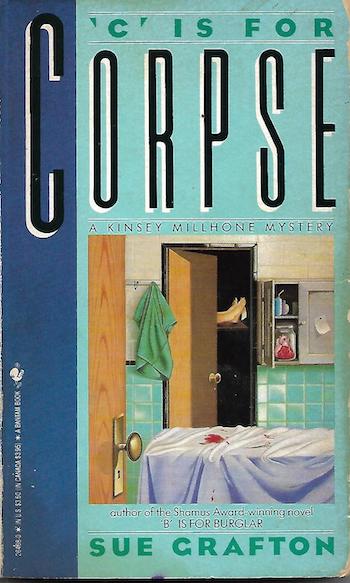

This past month I discovered, in my local Little Free Library, a softcover copy of an old mystery favorite of mine, Sue Grafton’s C is for Corpse. I decided to reread the book, some 36 years after its initial appearance. I liked it so much, I then took on the small project of rereading the two books that led off Grafton’s “alphabet series,” a string of 25 best-selling books that mightily assisted the emerging trend of female gumshoes.

I haven’t read much crime fiction in recent years. Back in my semi-regular mystery consuming years — the ’80s and ’90s — I focused mainly on Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, and, among the newer breed, Grafton, Robert Parker, John Lutz, and a few of Gregory Mcdonald’s and Lawrence Block’s more comedic books. In rereading the A, B, and C of Grafton — Alibi, Burglar, and Corpse — I renewed my old affections. And I experienced one minor revelation. I didn’t really care who killed whom. I was perfectly pleased to live, for a while, inside the narrative mind of Sue Grafton’s private eye, Kinsey Millhone.

Grafton’s climb to success as a novelist was formidable. Starting while a college student, wife, and mother at age 20, she wrote seven novels, eventually publishing two, Kesiah Dane and The Lolly-Madonna War. (The latter became a movie, Lolly-MadonnaXXX, starring Jeff Bridges and Rod Steiger.) For many years she made her living writing scripts for TV movies. (In a move fanaticized by many a struggling writer, Grafton destroyed the manuscripts of her five unpublished early novels.) She was 42 when her first Kinsey Millhone mystery was published, and she kept up the TV writing until her seventh bestseller, G is for Gumshoe.

One problem facing any long-running PI series is the aging process: how does a fictional detective fight, flee, dash, and dominate with unflagging energy in middle and old age? Grafton solves this niftily: Kinsey is forever in her 30s, and every book is set in the ’80s. This plan works on another level, too: The ’80s was also the last full decade that a fictional sleuth could track down clues without the pedestrian tool of the Internet. Kinsey depended on coincidence, perceptive guesswork, the personal interview, the public library’s microfilm collection, and a few favors from semi-friendly, infrequently flirty policemen. Like a lot of fictional private investigators, she had begun as a cop, but couldn’t tolerate police culture and its fiats. The idea of a fearless, hard-bitten loner trying to save the world — or at least solve the crime — has been a staple of urban detective novels for 90 years. Kinsey Millhone isn’t as crazily heroic as some of her male predecessors, but she shares with them many loner hero traits. She’s intractable, for starters. Police chiefs are still a private investigator’s entrenched enemy. And, in tribute to Raymond Chandler, her California turf, Santa Barbara, is renamed Santa Teresa, just as he did.

While fictional PIs play fast and loose with police procedures, the books themselves follow fairly closely to genre ground rules, something that Wilson claimed, with some justification, was evidence of their inferiority. One weakness of the “alphabet” novels is the supposedly breathless endings. Once it became clear the books were to be a series, it was hard to get worked up over the life and death struggles in the final pages. They became performative. We knew Kinsey wasn’t about to die!

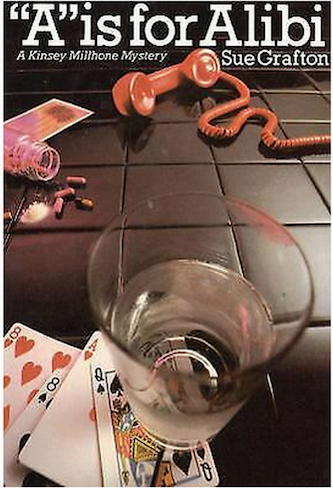

It must be said, though, that Grafton effectively mined her own stormy life much like many a primo literary novelist. In real life, Grafton’s father — a lawyer and mystery novelist — came back from service in WWII when she was five; both parents then promptly became full-time alcoholics. Grafton killed off Kinsey’s parents in a car crash when her heroine was five. In real life, Grafton married at 18, quickly had two babies, and divorced at 21. Briefly married a second time, she suffered a drawn out divorce replete with wretched custody battles over her third child. In her first Kinsey book, A is for Alibi, a main character suffers the same excruciating legal battles.

It must be said, though, that Grafton effectively mined her own stormy life much like many a primo literary novelist. In real life, Grafton’s father — a lawyer and mystery novelist — came back from service in WWII when she was five; both parents then promptly became full-time alcoholics. Grafton killed off Kinsey’s parents in a car crash when her heroine was five. In real life, Grafton married at 18, quickly had two babies, and divorced at 21. Briefly married a second time, she suffered a drawn out divorce replete with wretched custody battles over her third child. In her first Kinsey book, A is for Alibi, a main character suffers the same excruciating legal battles.

Grafton’s work rests midway between the cozy of Christie and the grisly of Lehane. While many male PIs are cast in the armor of foolhardy bravery, Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone is more realistically cautious. She is also less cynical: more apt to see the good side of people, though she reserves her judgment on those hard to fathom. And her life isn’t quite as lonely. Though she lives alone in a remodeled 225-square-foot garage, her landlord is a fatherly buddy: a dashingly handsome octogenarian baker and crossword puzzle creator named Henry Pitts. And her favorite neighborhood hangout is a dingy restaurant-bar owned by an outrageously bossy Hungarian named Rosie. So, there is at least a small sense of community. When Kinsey is on a case, she isn’t anybody’s fool, but she’s also honestly interested in the people she interviews, and quickly warms to the more benevolent ones.

Though Grafton counts as a feminist in the mystery genre, she is of an old-fashioned ’80s model: Kinsey Millhone calls out sporadic examples of male chauvinism, but she has no trace of political correctness. She frequently complains about fat people as if their bloated torsos and jowly chins were personal affronts. The physically attractive and well-dressed always get a goodly share of compliments. And Kinsey is well aware of certain men’s sex appeal, especially older men. The vainglorious rich tend to receive more gibes than the sleazy poor, but Kinsey is an equal opportunity insulter to the mendacious of all classes. The only gay male character I ran across in the three novels was a minor one, a bartender, and he met a bad end. But Kinsey seemed to like him well enough.

“I’m 32 years old, twice divorced, no kids. The day before yesterday I killed someone, and the fact weighs heavily on my mind.” These lines are from the first paragraph of the first Kinsey book. The tone may be matter-of-fact, yet it is less tough than the male PIs who preceded Kinsey Millhone. Kinsey is endearingly honest. And here’s a true anomaly in the detective genre: Kinsey is a PI able to poke holes in her own prejudices. The best example is B is for Burglar. After unleashing her acerbic wit at length about a (probably innocent) suspect and her middle-class neighborhood, house, furniture, hair-style, plumpness — she executes an about-face. “I hated this part of my job — inserting myself into somebody else’s pain and grief, violating privacy. I felt like a door-to-door salesman,” Kinsey narrates. “I also hated myself vaguely for being judgmental. What do I know about hairstyles anyway?” It is not an admission Philip Marlowe would make.

Edmund Wilson had a point when he complained about the needless details of detective fiction. This staple of PI books has existed, presumably, because PIs are in the business of noticing every detail as a possible clue. Grafton’s frequent descriptions of clothing, houses, and furnishings are surely excessive. More interesting is her mode of detailing the quotidian parts of the private eye job, like note-taking on index cards. And the way she leans upon garden-variety moments, everyday confabs, and unproductive ponderings often has purpose. They set up the satisfying shock of a swift plot development. Few would argue that even stylishly written detective fiction can compare in depth with the finest works of “serious” fiction. Yet in the moments when a mystery’s answers begin to reveal themselves, the reader can experience a jolt of such joyful focus! A satisfying rush ensues: especially after a chapter of amiable stasis. One becomes so alert at a well-executed moment of reveal.

Mystery lovers commonly defend the genre by crediting the sturdy storytelling. But strong storytelling empowers many types of novels. To put a finer point on it, an adroit mystery turns on intrigue, tension, release: a trio of dramatic aspects admittedly rare in our own humdrum lives.

The mystery crime novel — even the gritty, blood-letting ones — is essentially an escapist experience, true. The idea is that even the most baffling murders can be solved by a soldier of ethical right — given enough patience, acuity, and courage. That moral absolute is indeed like a fairy-tale equation transposed to the red-gash world of corpses and crime. The bodies may pile up, but justice prevails. The conveniently tidy endings do turn killing into an entertainment. They also allow us to briefly believe in redemption. And that is not the vainest of hopes.

Mystery writer Sue Grafton: her climb to success as a novelist was formidable.

The better crime novels portray a sleuth one is happy to identify with. This admiration of a hero — especially one who’s more human than super — is also nothing to be ashamed of. Psychic escape is an essential literary gratification: the ability to live with a character and imagine yourself entering the adventure! It is a novelistic staple purposefully absent in much so-called serious literature, and yet the whole invention of the novel wouldn’t have caught on without it.

One weakness of detective novels is a PI who is emotionally above the fray, the sleuth narrator who’s strictly the critic of a corrupt society, and whose poetic flair is purposefully purple, the metaphors not just muscled but steroidal. Grafton works a simpler canvas. I’m partial to A and C, the two books that have an emotional underpinning. My favorite is A is for Alibi. One can tell Grafton is writing as if her professional life depends on it: putting every ounce of her talent out there, but without any sense of stylistic overkill. Here was a writer in love with Southern California. The descriptions of nature often attain an uncluttered elegance. And there is also a sexual relationship here, with a suspect no less: a plot point that breaks the PI rulebook. (Did Mike Hammer ever have sex, or did he just salivate?)

The next best of the first three is C is for Corpse, and Kinsey’s emotional involvement is again paramount here. In the first paragraph we learn that young Bobby Callahan died three days after he hired Kinsey. It is a believable sibling-like rapport they strike up, and it powers the book. In all three books the alienated rich of Santa Barbara is a territory she flat-out owns. The niftily plotted B is for Burglar is the more awarded book, but I found it less involving. (I read it last, so it’s possible I’d just binged too long at the fair.)

It has been over four years since Grafton’s death, at 77, one volume shy of the last letter. Before her death she stipulated that “Z is for Zero” should never be ghostwritten, and that no TV shows or movies be made from her Kinsey novels. Her children and third husband agreed on what Grafton termed “a blood oath” not to sell out Kinsey Millhone. “If they do so, I will come back from the grave: which they know I can do,” she wrote. But the second of those two wishes has, just months ago, been betrayed: her family has sold her books to A & E Studios for future TV movies. So — these wealthy Santa Barbara schemers seem straight out of a Grafton novel: the tale of a corrupt, duplicitous family. Her widowed husband defended the decision by noting that TV movies have improved immeasurably since the ’80s, back when his wife wrote them. If Kinsey Millhone were on the case, she’d see right through this excuse. The truth is that TV movies have not undergone a transformation since 2017, when Grafton was still alive, kicking, and dead set against a TV Kinsey. We shall see if the blood oath commands the power of retribution.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Tagged: Daniel Gewertz, Edmund-Wilson, Kinsey Millhone, Mystery novels

Good to have Edmund Wilson’s high-hat response to mystery fiction given a shout-out. Some background — this was the second of a three-part series in which he attacked the genre. The dramatic premise is that, after the first installment, Wilson had been besieged by letters from incensed defenders, insisting that he had not read the best mysteries. So the critic asked them for some titles and in “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” he reported on his reaction to their recommendations, which included books by Dorothy Sayers and Ngaio Marsh. Along the way he takes on some of genre’s literary admirers, including Jacques Barzun and Somerset Maugham, and quotes from hostile letter writers. Wilson concludes that the “reading of detective stories is simply a kind of vice that, for silliness and minor harmfulness, ranks somewhere between smoking and cross word puzzles.”

In his wind-up, Wilson insisted that he was defending Literature:

“To detective-story addicts, then, I say: Please do not write me any more letters telling me that I have not read the right books. And to the seven correspondents who are with me and who in some cases have thanked me for helping them to liberate themselves from a habit which they recognized as wasteful of time and degrading to the intellect but into which they had been bullied by convention and the portentously invoked examples of Woodrow Wilson and Andre Gide — to these staunch and pure spirits I say: Friends, we represent a minority, but Literature is on our side. With so many fine books to be read, so much to be studied and known, there is no need to bore ourselves with this rubbish. And with the paper shortage pressing on all publication and many first-rate writers forced out of print, we shall do well to discourage the squandering of this paper that might be put to better use.”

His point still holds — there is so much of quality to read and time is fleeting. By the way, is there a current New Yorker critic who would invite readers to respond to their critiques? And then fire back?

A superb essay, Dan. As someone who doesn’t care who killed Roger Ackroyd, I appreciate learning about Sue Grafton and your knowing defense of her books, flaws and all. I am sending the essay to a brilliant Chicago friend of mine who loves great literature AND Grafton.

Thanks, Gerry. I have to add that, post writing my piece, I tried a book of hers late in the series, a slightly more experimental one (S) and was not pleased. My thought is, if any type of writer publishes 30+ books in nearly as many years, they tend not to be worth my slow-reading time.

The fictional town of Santa Teresa was created by Ross MacDonald not Raymond Chandler.

Late reply: You are right, Dennice. I got my 2 fave mystery writers mixed up on that important detail. Thanks for the correction.

Every so often I jump on the internet to see what

“it’s” doing to my heroine Kinsey…and Sue. Been one of her greatest fans since late 80’s, always anxiously awaiting her next adventure…year after year after year. Didn’t take long for her fam to go against her dying wishes. Personally I would NOT want to piss off that woman,dead or alive! Really enjoyed reading your essay!!!!

I’m typing in 2024, and there’s been no update on the TV deal since it was announced in late 2021. In fact there is so little news about it that this thoughtful piece comes up fairly high in the Google search. Dare we hope that Grafton found a way to haunt her family after all?

I don’t always think the wishes of the dead need be sacrosanct – this world with its large bills to pay is for the living, after all. But Sue Grafton was so adamant about this for so long. And given her time working in television, she was not just objecting to an idea, or a vague theory. She was objecting to a world that she knew, and knew intimately. I think this is quite a different posture than someone saying “no” only because they are stubborn or afraid of new things.

Besides – the era of “peak TV,” which the family used for their excuse, is now basically over. The streamers and networks are all producing painfully few Mad Mens, and many many reality series. The time to do this and ensure maximum respect for Kinsey Millhone would have been a decade ago.

If anyone can provide a reference to an “authorized” cross-reference between the names Grafton gives Southern California cities and their actual names [e.g., “Santa Teresa = Santa Barbara”, I’d dearly love to peruse it.

Interesante artículo sobre la escritora de novelas de misterio Sue Grafton y su personaje Kinsey Millhone.