Visual Arts Interview: Lisa Kessler’s “Heart in the Wound” — Reassessing Sexual Abuse, Power, and the Catholic Church

By Bill Marx

“The abuse in the church has very unique and cruel twists to it. And, as one of the oldest continuous patriarchal institutions in the world, looking at the church helps us to reflect upon how many established institutions, including families, help perpetuate and conceal violence throughout society.”

Photographer Lisa Kessler. Photo: Dominic Chavez.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Boston Globe’s expose of clergy abuse, and for some the sober occasion serves as more than an invitation for reflection or self-congratulation. These commentators and artists view it as a call for recommitment, for expanding our understanding of how the behavior of the Catholic Church, particularly its continuing cover-up of its maleficence, reflects larger systems of patriarchal repression and domestic violence throughout society. Lisa Kessler‘s powerful exhibition Heart in the Wound (at Boston’s Howard Yezerski Gallery through March 26) is the only collection of still photographs that documents the revelations of the church’s crimes by looking deeply at the church, the protests, and the survivors. The gallery is also presenting (available on headphones) an 8-minute edited version of Kessler’s 20-minute film Heart in the Wound, which can be seen in full on her website. The 2006 movie integrates still imagery and the voices of three survivors, Kathy, Phil, and Olan.

For Kessler, the show aims to make viewers uncomfortable, to stimulate much needed dialogue, to take a look at “the public and private spheres around the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church to bring us to the broader, common issues of sexual violation and abuse of power.” Be aware: the images and film may be triggering.

Kessler teaches at Simmons University and Boston College and her work is in the permanent collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Teaching Museum of Lehigh University. I emailed her some questions about her show, with an emphasis on learning how her assessment of the Catholic Church’s crimes — and the public response — has evolved over the last 20 years.

Discussion of interest: On March 26 at 1 p.m, at More Than Words, 242 East Berkeley Street (a five minute walk from the gallery), there will be an Artist Talk, “Images as Action and Reflection,” featuring Kessler, Kathy Dwyer, and S. Billie Mandle. The conversation will be about responding to the on-going tragedy of systemic sexual abuse. How do we ignite change, pause for reflection, and build on a shared commitment to looking as an opportunity for transformation?

Arts Fuse: This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Boston Globe’s expose of clergy abuse. Your show is among the events marking the occasion. What does Heart in the Wound bring to the reconsideration?

Lisa Kessler: This is the only collection of still photographs that documents the revelations of the church’s crimes by looking deeply at the church, the protests, and the survivors. It reminds us that clergy abuse survivors forced Americans to reassess how they think about sexual abuse, power, and the Catholic Church. Their courage is a significant transitional force from a culture of silence, invisibility and denial, to a contemporary culture of reckoning, transparency, and Me Too solidarity.

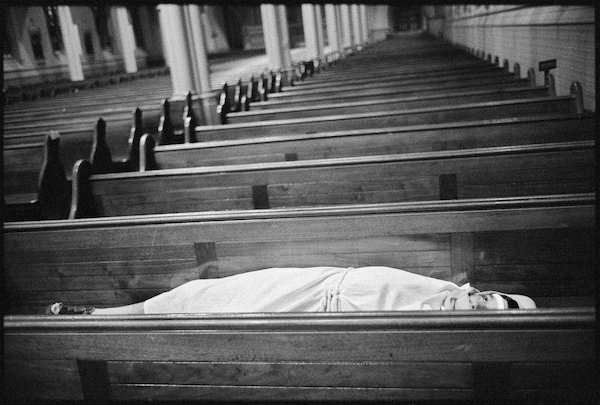

Lisa Kessler, “Passion Play,” 2002.

AF: Talk about the relationship between your film, Heart in the Wound, and the photos in the show. Do the photographs provide a distinct experience?

Kessler: The 2006 film integrates still imagery and the voices of three survivors, creating a 20- minute narrative experience. There are about 70 images in the film. Even though the images aren’t presented chronologically, and the voices aren’t describing the images, the film is a linear experience, with a beginning and an end.

The show at Howard Yezerski Gallery has 18 prints – a tight edit that includes four images from BEFORE the scandal, and two that were not included in the film. Looking at prints on a wall gives you time to explore the layers captured in a single frame. Those layers help contextualize the moment, build a broader metaphor, or relate to another image in a way that adds meaning to the experience. There are also headphones available in the gallery with 8 minutes of audio from the film.

I think that seeing the photographs on the wall might leave viewers with more questions than answers, and that’s good. The subject of my work is inherently uncomfortable for people, and I hope the exhibit gives viewers a better foothold in difficult terrain. This isn’t an issue that I’m trying to tie up neatly with a bow.

AF: Do any of the photographs have special significance for you? If so, please explain why

Kessler: Each photograph takes me back to a specific time and place and mood, and to the relationships that brought me there to make candid images. “Passion Play” is special because it speaks symbolically to the revelation of crimes in the Catholic church, and more broadly to anyone who has felt unseen or unheard inside a large structure or institution. Years ago the image was included in “Giving Shelter,” an exhibit at a contemporary art museum in Albuquerque. In that case, the image spoke symbolically of a child alone and unsheltered – unprotected – in what should be a safe space. I like photographs that are both true to the moment and the context, and also resonate on deeper levels.

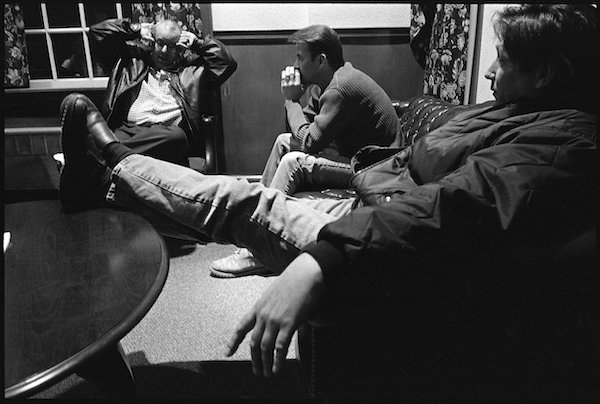

Lisa Kessler, “Survivors of Joe Birmingham,” 2003.

“Survivors of Joe Birmingham” is also very special because of the trust extended to me by the men in the group. SOJB is a private support group of men, then in their late 20s to 70s, who had all been abused by the same priest over many decades. 128 came forward – molested by that one priest, in five parishes over three decades.

Even with the access, it was difficult to capture the emotion in those rooms. Unlike working inside the church, where garb and architecture are full of symbols, there isn’t much symbolism in this scene – only body language. I was struggling to convey in still photographs the more complicated emotional and psychological realities, and ended up doing in-depth interviews with three survivors, including Olan Horne, at right, and Kathy Dwyer. Their voices are the soundtrack of the film, and can be heard at the gallery or on my website.

By the way, Olan and Kathy are still fighting to bring justice to survivors of clergy abuse.

AF: Why did you choose to use black and white? What power do you think that approach brings to the subject?

Kessler: Black and white is my first language as a photographer. The show includes work from 1990-2004, a time when I processed my own black and white film and made my own black and white prints. Black and white gave me the greatest freedom to work candidly with available light, whether in dark interior spaces or bright outdoor scenes. I loved making my own prints in the darkroom, which I could only do in B/W. Color would have been prohibitively expensive for a long term documentary project like this.

Over the course of my career I’ve photographed in color for assignment work – first in slides, then color negative film, and now digital. Digital photography and digital printing made it possible for me to make personal work in color; I started my project “In the Pink” in 2007.

Aside from all the technical logistics, black and white is powerful because it simplifies a scene and eliminates color as a distraction. I think composition is paramount in black and white, and I love the challenge of creating a sense of depth with just shades of gray.

AF: You write that you felt “conflicted and betrayed. … as a non-Catholic who empathized deeply with the victims/survivors.” How do you feel after 20 years? Does the show reflect any changes in how you look at yourself? The victims/survivors?

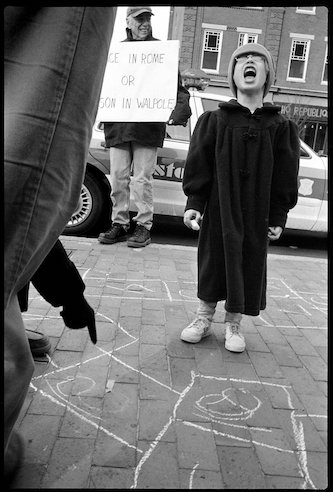

Lisa Kessler, “Scream,” 2002.

Kessler: I don’t feel nearly as conflicted today; I feel the work has withstood the test of time and still speaks to both the structural and emotional issues broadly exposed in 2002. I always understood that what we were seeing play out in the Catholic church was a lens into how civil society functions as well. Yes, the abuse in the church has very unique and cruel twists to it. And, as one of the oldest continuous patriarchal institutions in the world, looking at the church helps us to reflect upon how many established institutions, including families, help perpetuate and conceal violence throughout society.

AF: A January 2022 commentary in the National Catholic Reporter argued that after “the Boston Globe‘s Spotlight series and the cascading revelations that followed, the word “crisis” now rings hollow as it applies to clergy sexual abuse. It is no longer meaningful to refer to clergy sexual abuse as a crisis. As the shame and anger moved from the offending cleric to the systemic cover-up by bishops, we now must face the grim reality that the most profound shame is the ongoing, real-time failure to act in a decisive manner to address the ‘abandonment of the little ones.’ ” Would you agree? Is Heart in the Wound an effort to make us “face the grim reality.”

Kessler: This powerful commentary is from Barbara Thorp, who led the Boston Archdiocese’s office that responded to survivors, and for whom I have much respect. I agree thoroughly that it is no longer meaningful to refer to clergy sexual abuse as a crisis, and I try to be careful not to fall into that habituated language. I try always to remember what the church wouldn’t face: that this is about CRIME, and the revelation of those crimes hidden by the church and by society.

Jason Berry, who first wrote of clergy abuse in the ’80s, tried to pitch his investigative work as an “abuse of power” story, akin to Watergate. But mainstream media and society at large were not ready to hear an “abuse of power” story in the church. Times haves changed, and we have the survivors of clergy abuse to thank for turning the tide so that all victims of sexual assault feel more empowered to speak up, and are now more likely than not to be believed.

The “grim reality” has always been right there in front of us. The question I like to ask myself, and through my work encourage others to ask themselves, is “Am I someone who a child or a vulnerable adult would come to if they were being harmed? Would I know what to do and what to say”? I’m an optimist, but also a realist: people hurt each other. How we respond influences the impact of that harm.

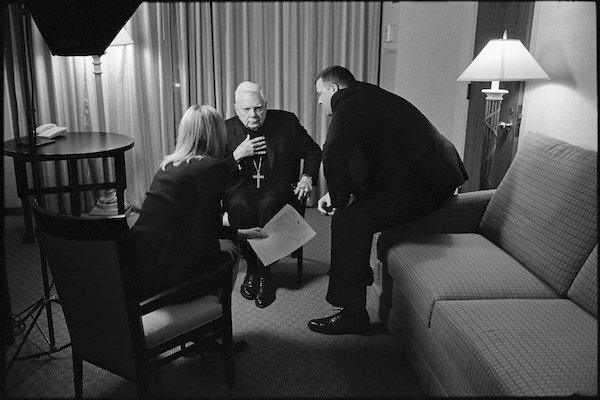

“Advisors,” Lisa Kessler, 2002.

Many institutions have been facing the “grim reality” of their failures, and are coming to understand the cost in human lives. More people are holding them accountable for the structural nature of their failures and cover-ups, and working to advance dialogue and conversations around transparency and accountability. In that vein, Heart in the Wound is part of that process, reflecting what our society is, and trying to create systems of power rooted in transparency, vulnerability, and accountability.

After the show at Howard Yezerski Gallery, I hope to continue exhibiting this work, ideally with the artist S. Billie Mandle and her work Reconciliation. Collectively our two bodies of work create a powerful dialogue and exponential impact. My work looks out into collective public space, the world of activism, institutions, and politics, while Mandle’s work creates a safe, vulnerable respite, drawing the viewer back into self-reflection. Mandle’s quiet pilgrimage was singular and personal; seen with my work, it brings forward the journeys of all survivors, each still having their own reconciliations, long after the news cameras have gone. Together, the two modes of observation offer a mechanism for transferring shame from wounded individuals to the structures that caused the harm.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Bill-Marx, Catholic Church, Heart in the Wound, Howard Yezerski Gallery

Fabulous piece, high five!

Thank you Lisa! Remember me? I sold you my Nissan Sentra back in the 80’s! Love that you’re doing so well. I left the priesthood 12 years ago to make a new life for myself in FL as a Life Coach and Spiritual Director. Check me out at http://www.mpariselifecoach.com

Michael