Jazz Album Review: Ran Blake’s “Looking Glass” — Music from an Idiosyncratic Guru

By Jon Garelick

This album offers a Baedeker of pianist Ran Blake’s cinematic effects, the mise-en-scène for a narrative musical imagination unlike any other.

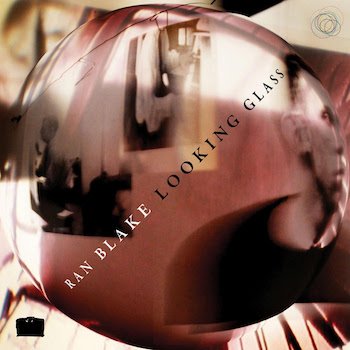

Ran Blake, Looking Glass

If you wanted an introduction to Ran Blake — now 86 years old and more than 50 albums in — this online-only solo-piano release isn’t a bad place to start. Here the idiosyncratic guru of New England Conservatory’s Third Stream department (now Contemporary Improvisation) offers a Baedeker of his stylistic hallmarks — the noirish chiaroscuro of light and shadow, the rapidly shifting dynamics, the use of silence and pedaled sustains, the extraordinary ear for harmony. There’s also the deep interior exploration of form (standards and otherwise). All of it is informed by Blake’s film noir obsession (he likes to describe his approach to improvisational composition as “storyboarding”). And all of it in 16 songs in 37 minutes, three of them under a minute long.

The program includes a mix of originals and covers, familiar and rare, including several tunes whose titles are explicitly autobiographical. But then, Blake’s music has always been autobiographical in one way or another. There are people and places from throughout his life, going back to his childhood, in Springfield, MA, and then Suffield, CT: “Mary Garvey” (a household cook and maid), “Arline Cunningham” (a friend from the Lenox School of Jazz, where Blake spent a few summers), and “Sister Tee” (a colorful character from Blake’s early years in New York, who was, among other things, a chorus director at Sweet Daddy Grace’s Pentecostal Church in Harlem, where Blake was a regular). And there are places like “Cemetery at Mulberry,” where he found solitary comfort as a child, and “Jinxy,” a jazz club in Hartford. The noir storyboard in “Cry Wolf,” is inspired by the 1949 film “The Window” (dir. Ted Tetzlaff), “in which a little boy witnesses a murder but no one believes him.”

Aside from the gospel outbursts of “Sister Tee” and some stride figures in “Jinxy,” the tunes here are taken at a predominantly ballad tempo — you don’t come to Ran Blake for jazz swing and fast right-hand runs. What you do come for are the stories in the songs, the deep interiority of each. Blake, with his cinematic obsessions, has compared himself with film directors, but he’s more like a method actor, becoming the role of each song, looking for the story within the story.

Pianist Ran Blake. Photo: courtesy of the artist

So one Thelonious Monk tune, “’Round Midnight,” begins by quoting another, “Pannonica,” shadowed by a tolling left-hand figure before the main melody enters. There are embellishments and departures, the melody treated with gentle affection, then stating itself more boldly, and always that shadow of a left hand. As the bits of the song come in and out of focus, you realize that this isn’t just “’Round Midnight,” but maybe more properly a memory of “’Round Midnight,” and all the associations it conjures. (During a portion of Blake’s time in New York, he was a friend of the Monk family, even babysitting and cooking for the children.)

“’Round Midnight” ends abruptly, unresolved, as do several of the pieces here — like waking from a dream. Though the pieces can become somewhat abstract, they begin and return to melodies, several of which are quite lovely. And an upbeat piece like “Jinxy” could almost be a show tune, with a call-and-response chorus that you could imagine the sailors singing in On the Town. And when the dark, almost foreboding “Thursday” breaks for a pattern of blaring chords, they could be blasts from the Stan Kenton brass section (a band whose more experimental charts by Bill Russo were an early inspiration for Blake). For that matter, you can hear a horn section in Blake’s playful treatment of Ornette Coleman’s “Turnaround.”

But those are examples of Blake’s orchestral approach to the keyboard in selections that are more often ruminative than rocking. The ghost-like pedal effects, the tolling four-to-the-bar left-hand chords that quietly stalk the right-hand melodies, the sudden splash of fortissimo staccato chords — all are part of Blake’s cinematic effects, the mise-en-scène for a narrative musical imagination unlike any other.

Jon Garelick is a member of the Boston Globe editorial board. A former arts editor at the Boston Phoenix, he writes frequently about jazz for the Globe, Arts Fuse, and other publications.

A fine tribute to Blake, who, alas, I saw brought out in a wheelchair the other night at Jordan Hall for a night of Abbey Lincoln music. Blake’s appearance was at the end of the concert, and, though severely crippled, he managed to play on the piano a beautiful song in the pitch dark with a woman singing the Abbey Lincoln part. After that, an enormously touching standing ovation from those who appreciate what Ran Blake has brought to jazz, has brought to Boston.