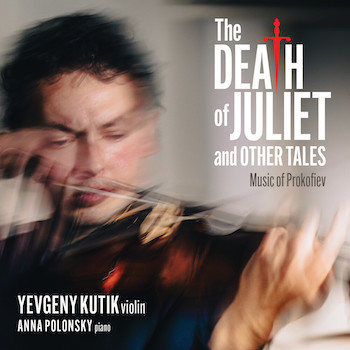

Classical Album Review: Violinist Yevgeny Kutik — “The Death of Juliet and Other Tales”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The program is compelling, but some of violinist Yevgeny Kutik’s interpretations could sing more freely and dance more nimbly.

Nearly everything violinist Yevgeny Kutik programs and records has some sort of deep, personal connection to him – either his musical training or his family upbringing. The situation is no different in The Death of Juliet and Other Tales, which pairs pieces by Sergei Prokofiev (who Kutik’s teacher, Roman Totenberg, knew) and folksongs the violinist grew up hearing in his Belarusian family.

Nearly everything violinist Yevgeny Kutik programs and records has some sort of deep, personal connection to him – either his musical training or his family upbringing. The situation is no different in The Death of Juliet and Other Tales, which pairs pieces by Sergei Prokofiev (who Kutik’s teacher, Roman Totenberg, knew) and folksongs the violinist grew up hearing in his Belarusian family.

As usual, the set itself is compelling. In addition to Prokofiev’s Sonata for Solo Violin, his Violin Sonata no. 2, and an arrangement of music from Romeo & Juliet, there are four traditional songs heard in settings by either Kutik, Michael Gandolfi, or Kati Agócs.

Perhaps the most familiar of those last are the “Song of the Volga Boatmen” and “Yablochka,” the latter of which was memorably incorporated into Reinhold Gliere’s ballet The Red Poppy. On the present album, both are heard in Gandolfi’s winning, idiomatic adaptations: the former, mighty and muscular; the latter, sweetly mournful.

Kutik’s reworkings of “V Lesu Rodilas Elochka” and “V Pole Berez Stoyala” mix atmosphere and virtuosity, while Agócs’ “Kalinka” channels Kutik’s inner Slavic folk fiddler.

These songs connect smartly with the disc’s mellifluous Prokofiev selections.

Romeo & Juliet is one of his most astoundingly lyrical creations and the “Parting Scene and Death of Juliet,” played here with pianist Anna Polonsky (who also accompanied “Song of the Volga Boatmen” and “Kalinka”), is aptly soulful and warm-toned; the sequence of harmonics at the end is downright stunning.

It comes as a bit of a surprise, then, that the disc’s two subsequent Prokofiev offerings prove less satisfying.

Kutik’s take on the D-major Solo Violin Sonata doesn’t want for intensity or delicacy. To be sure, there are captivating moments here: much of the first movement is gently ingratiating, the Andante’s songful moments really speak, and the finale’s Allegro precipitato episodes unspool vigorously.

Yet his larger approach feels off. Kutik’s phrasings of the Moderato’s opening motive, for instance, are too strict; they quickly take on an episodic quality. In the Andante, the scherzando and sextuplet variations are similarly rigid, lacking grace and charm. And, in this performance, the exaggerated starts, stops, and pauses of the finale’s recurring first theme end up robbing the rest of the movement of much-needed momentum.

For comparison, check out James Ehnes (on Chandos) or Gil Shaham (on Deutsche Grammophon) playing this same piece. Like Kutik, both ably capture the Sonata’s inherent sweetness. But their phrasings are more natural, understanding of the music’s character less self-conscious. The resulting interpretations sing more freely and dance more nimbly.

Likewise, the 1943 Violin Sonata no. 2 doesn’t come across here as strongly as it might.

The Moderato and the Andante are most persuasive. In the former, everything’s very tight, rhythmically: the distinctions between duple and triple rhythmic patterns are conspicuously fine. So, too, the give-and-take between rhythmic textures in the lovely slow movement. There, as well, the songful episodes are radiant and unaffected.

However, the Presto’s outer thirds need more horsepower from both Kutik and Polonsky: they’re too gentle throughout. While the central Trio is fine, it would benefit from mightier contrasts of character, dynamics, and attack.

In the finale, Kutik’s essentially snappy, vigorous violin playing fits the music rightly. But the keyboard part sounds colorless and subdued by comparison. Textures are clear and the duo makes the most of the movement’s transition to the dreamy middle section, but the reading misses the frisson of Oistrakh/Yampolsky – or Mutter/Orkis, for that matter.

Part of the issue might be the disc’s engineering: in the Sonata, the violin sounds well forward of the piano. Given that both players clearly have all the notes under their fingers, maybe that best explains the absence of impish spirit in this music’s more extroverted moments.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Jonathan Blumhofer, Marquis Classics, The Death of Juliet and Other Tales