Music Commentary: In Memoriam, George Crumb (1929-2022)

By Jonathan Blumhofer

George Crumb, who crafted some of the 20th century’s most brazenly original-sounding and haunting music, lived his life and guided his career on his own terms.

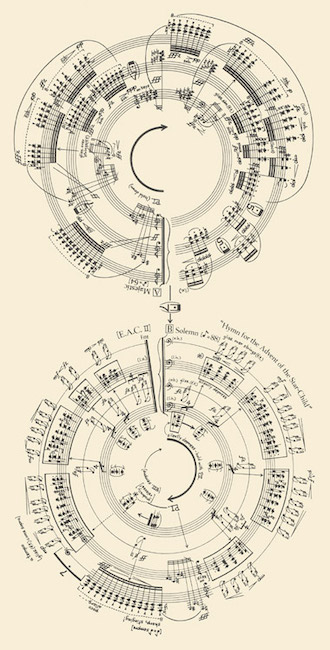

A George Crumb score.

In his last decades, George Crumb, who died Sunday at 92, wasn’t — like Elliott Carter — the recipient of high-profile commissions and adulatory press reports. Nor, like Pierre Boulez, was he loudly feted as one of the last living 20th-century visionaries linking the past to the present.

That’s not to say Crumb wasn’t among the latter; he most certainly was. Or that he wasn’t prolific over his last 20 years. He was that, too.

Rather, it was a reminder that Crumb, who crafted some of the 20th century’s most brazenly original-sounding and haunting music, lived his life and guided his career on his own terms.

Famously down-to-earth and approachable, Crumb was the antithesis of the imperious Boulez and the eccentric Karlheinz Stockhausen, two of his contemporaries who were equally adept at turning convention on its head.

Not that he came from terribly different musical origins. Though born in West Virginia in 1929 and raised on a rich blend of folk, popular, and classical traditions, Crumb’s earliest work reflected a prevailing interest in the Serialism of Anton Webern and the Neoclassicism of Igor Stravinsky. It wasn’t long, though, before his own voice found its way through.

At its most striking, Crumb’s mature musical language was at once avant-garde, traditional, expressive, and theatrical. In a way, he was the American equivalent of Luciano Berio and György Ligeti, able to conjure some of the most beguiling or harrowing gestures and textures imaginable, yet always crafting them into coherent, dramatic structures.

When Crumb hit his prime in the 1970s, he managed all this bracingly. The string quartet Black Angels, composed in 1970, was a genre-bending protest against the Vietnam War that called for the ensemble’s instruments to be amplified and for the players to also utilize various percussion instruments. Vox Balaenae, a dazzling 1971 trio for flute, cello, and piano, channeled extended instrumental techniques as well as costuming and lighting effects.

Somewhat less theatrical (but not by much) were the collection of four books that comprise Makrokosmos. Their title a play on Belá Bartók’s pedagogical keyboard collection Mikrokosmos, the first two books (from 1972 and 1973, respectively) again draw on extended keyboard techniques and amplification; the third (1974) is for piano and percussion, while the fourth (1979) was written for piano four-hands.

Though Crumb’s orchestral output was small (he preferred the flexibility of chamber ensembles), his magnum opus, the 1977 epic Star Child, rivals Charles Ives’s transcendent Symphony No. 4 in scope and complexity. Notably, it was for an orchestral piece, 1967’s Echoes of Time and the River, that Crumb was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

A creative block kept Crumb on the sidelines for much of the 1980s and ’90s, though he returned in force in the 2000s. In particular, the seven American Songbook installations that appeared between 2003 and 2010 demonstrate the composer’s clear affection for his source materials (hymns, spirituals, folk songs, and the like), as well as his continued astonishing ear for sonority.

The late composer George Crumb. Photo: Wiki Common

Throughout his career, Crumb’s understanding of musical notation — a peculiar art, if ever there was one — was singular. And, though he only employed circular notation (in which the hand-drawn staves appear in a kind of vortex) sparingly, the technique often enough reflected the sound of his music, visually.

My own introduction to Crumb’s music came in college when I first heard Ancient Voices of Children, one of the pieces that employs his special system of notation. Written in 1970, Voices is perhaps Crumb’s most famous setting of poetry by Federico Garcia Lorca; the debut recording with Jan DeGaetani, Michael Dash, Gilbert Kalish, and the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble was one of the all-time best-selling new music albums.

Regardless, it’s music of gripping, eerie intensity, full of extended techniques (including the soprano singing into the strings of an amplified piano) and nontraditional instrumentation (there’s a musical saw and Japanese temple bells, among other things).

Yet what impressed me from the start was Voices’ tightly focused dramatic shape. This was entirely intuitive — as an 18- or 19-year-old I wasn’t yet consciously thinking of music in terms of form and structure, and certainly not on first hearing. But the impression the piece left was visceral. Though its content was, on its own, disorienting, it was framed in a way that was meaningful, unforgettable. Ever since that first encounter with Voices, I’ve been an admirer of Crumb’s. I imagine I’m not the only one with such a story.

Later on, I came to learn of his “four B’s” — Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, and Bartók — and the connection between form and content in Voices (and Black Angels, Vox Balaenae, and the rest) made perfect sense. Crumb’s reverence for the past was real, but, remarkably, he was never hindered by it. That should be a lesson for all of us.

So should his constant striving after perfection. In a 1988 interview with Bruce Duffie, Crumb revealed that he had yet to write “the kind of music I would like to write in my heart of hearts.” Whether he managed to do so over his next three-plus decades is an open question. Either way, the musical legacy Crumb leaves behind is that of a true American original.

A Short Crumb Videography

Ancient Voices of Children (1970)

Black Angels (1970)

Vox Balaenae (1971)

American Songbook, vol. 1: “Shall We Gather at the River?” (2003)

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Ancient Voices of Children, Black Angels, George Crumb