Film Review: “Ronnie’s” — The Story of a World-Famous London Jazz Club

By Daniel Gewertz

Mel Brooks called Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club “a little nest of happiness. All our recent wounds are healed there.”

Ronnie’s, a film directed by Oliver Murray, at select theaters and on demand, February 11.

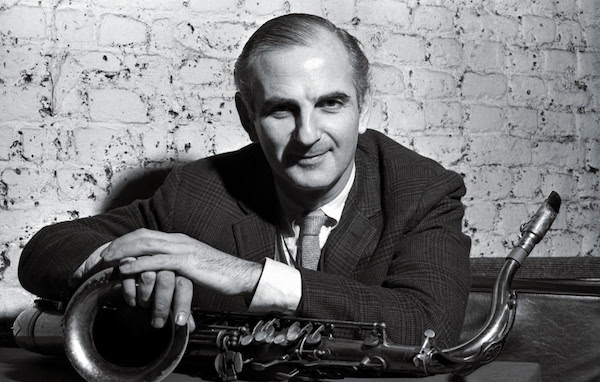

London club owner Ronnie Scott, the subject of the documentary Ronnie’s. Photo: Oliver Murray

Ronnie Scott was, on the surface, a man as lucky as he was talented. By his early 20s he was frequently voted the top tenor saxophonist in British jazz polls. From 1959 to 1996 he achieved something considerably more singular: owning a world-famous jazz club and keeping it in business not only during the few years still hip to jazz, but the long decades less enamored of the genre’s allure. That has to be an upbeat story of good fortune and artistic glory. And the stylish British documentary Ronnie’s is, at first, just that. Glorious bursts of music — from Miles to Basie, Dizzy to Zoot, Sarah Vaughan to Van Morrison — enliven the party. For its first hour, Ronnie’s appears to be one of those too rare tales of true art surviving the perils of a risky marketplace. But there is a ghost at the story’s center. A shadow reality at work.

For all his charm, Ronnie Scott (born Schatt) possessed a darkness that writer-director Oliver Murray knew he couldn’t avoid. For quite a spell he tries to. It is nearly the 60-minute mark before the film reveals the first of the club-owner’s failings: Scott was a compulsive gambler. He’d often grab the entire night’s “take” out of the cash register and gamble it away in the hours before daybreak. By the late ’60s, when word sporadically seeped out that the London club was facing ruin, the public might have assumed it was just a financial byproduct of the jazz genre’s fading commercial circumstances. The club’s co-owner — Scott’s best friend, Pete King — knew better.

The film hits the two-thirds mark before Murray finally reveals Scott’s more serious lifetime plague: depression. This delay tactic is shrewd. By this point we’ve not only enjoyed frequent, if brief, spates of star-laden jazz, but the doc has cemented a view of Scott as a droll emcee, a facile raconteur, a man liked, even loved, as a wryly humorous, fascinating fellow. His closest friend, fellow saxophonist King, was, as luck would have it, a whiz at the business side of things. While Scott mightily tried his patience, the friendship and the partnership flourished. Substantial love relationships with two intelligent, exquisite looking women are also part of the emerging picture of Scott’s adult life. He had two daughters. And yet, depression pervades. About the only way he could beat down his darkness was with sax-therapy: playing his tenor onstage assuaged his pain, but only on the nights he reached peak expressiveness. With two disparate tales to tell, the film can feel segmented, both emotionally and thematically. Scott treated his jazz stars with warmth and generosity. He didn’t treat himself nearly as well.

In the jazz club’s first location — an unprepossessing basement setting on a dicey Soho street — dissolute if colorful characters, including racketeers and strippers, would mingle agreeably in the early morning hours. This tough crowd felt protective of Scott. They were proud he was lending seamy Soho some class, and doing it in a cultural way unthreatening to their own less than noble activities. One of the club’s frequent fans was the area’s top gangster — known as Italian Albert Dimes. His mere presence scared off the two-bit hoodlums desiring “protection money” from the fledgling club, and he felt so supportive of the novice club owners that he never accepted offers of free entrance.

Ronald Scott was one well-loved guy.

The scene at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in Soho. Photo: Oliver Murray

The film starts off with Scott’s boyhood in the ’30s: a poor Jewish kid growing up in the Aldgate section of East London. Scott’s father, also a saxophonist, abandoned the family when the child was three. Ronnie started playing sax professionally at 16. While still a teen he was hired by England’s top jazz bandleader, Ted Heath. By the late ’40s Scott worked on the New York–bound Cunard cruise ships, a gig that offered him not just a steady paycheck, but something far more valuable: the chance to see his American bebop idols in Manhattan nightclubs. Since American stars didn’t play London, these visits, up to a week long, were like entering bebop heaven. Or as pianist Georgie Fame put it, “We were transported to dreamland.”

On one voyage back to England, Scott gazed at the ocean and dreamed up the whole plan for his future club. “Let’s face it,” he said years later. “You have to be an idiot to open a jazz club.”

Several of the on-camera interviews are new, but the doc is blessed with a steady supply of archival footage, including a fair amount of Scott, shot in the ’80s and ’90s. We see him play and banter onstage. He was often self-deprecating about both his onstage humor and his musical abilities. Though the thrill of his life was booking and befriending the American jazz masters, their brilliance must have dimmed his own confidence. It sometimes feels as if the man himself has come back from the grave, making us privy to his ruminations. The old footage is artfully sewn into the film.

Artful is the key word here. Apropos of a film about a moody jazzman, music supervisor Alex Heffes employs a mix of emotionally evocative music, especially effective in transitioning from scene to scene. Even the film’s visual rhythms seem jazzy. The documentary has no scripted narration, so several points remain hazy. We learn the facts in conversational style, provided by the interviewees. Ronnie’s is being advertised as if full-length performances by the icons of classic jazz are at the essence. Not true. The music clips are somewhat fuller than in some TV jazz docs, but if you’re looking for complete tunes you’ll be disappointed.

One of the most satisfying performances is a true surprise: a 1980s version of Stephen Sondheim’s “Send in the Clowns,” done in a half-talking style by Van Morrison, with a sublimely moody Chet Baker on trumpet. In other clips, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Oscar Peterson, and Dizzy Gillespie shine, briefly. Only Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald get a full song apiece.

The Sonny Rollins and Quincy Jones interviews are profound. “My life wouldn’t be complete without knowing Ronnie and Pete,” Rollins said. One hearty, hilarious interview clip is of a middle-aged Mel Brooks. “Ronnie Scott’s is a little nest of happiness,” he said. “All our recent wounds are healed there.”

Jimi Hendrix’s appearance at Ronnie Scott’s as a surprise performer with Eric Burdon & War must be mentioned for historical reasons. It was September 16, 1970, his last gig on this earth, less than two days before his heroin overdose death. A video camera caught a few seconds of Hendrix’s jubilant entrance to the stage, but there exists no video of the performance. We hear a short blues solo on audio only. (The Hendrix bit is available online. (Jimi Hendrix’s Final Performance: Hear Restored Version From New Doc – Rolling Stone)

The fact that Eric Burdon was at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club indicates the changes that had transformed the venue in the ’60s. Scott and King moved the club in 1965 from their modest beginnings on Gerrard Street to a larger, plusher three-floor operation on nearby Frith Street. Though the film doesn’t spell it out, the move was about more than just venue size: it was a way to save jazz in London at the precise point that British rock was taking over. As small jazz joints in the US were losing their audiences to rock clubs and discotheques, Scott and King inaugurated a triple-decker operation where all three breeds of nightspots could thrive. In the late ’60s, King and Scott’s vision of the club reached its fruition: one club that encompassed the whole burgeoning music scene of swinging London. As Scott says, it was easier to mention the few jazz stars who didn’t appear at the club instead of the legion who did. From the trio of Bill Evans to the big bands of Buddy Rich and Count Basie, Ronnie Scott’s became the spot to play in Europe.

The move took advantage of the biggest stroke of luck in Scott’s professional life. In the early ’60s, all the London club owners found it nearly impossible to hire American players because of stringent US musician union rules. The regulations demanded that a British act play the US for every American act shipped to England. But in 1964, the Beatles launched the British Invasion. Within months, there were so many English rockers desiring US tours that top American jazz stars lined up to play Ronnie’s. In exchange for a Freddie & the Dreamers, a Dizzy Gillespie could play the club; for a Herman’s Hermits, an Ella Fitzgerald could visit, along with her band. “The bargain of the century was Sonny Rollins for the Sex Pistols,” bragged King in the ’70s.

The film leaves certain questions unanswered. Was Mary Scott a wife and, ultimately, a widow, or, as the film states, “a partner?” More important is the vague matter of Scott’s final year.

What we gather is this: In his late 60s, Scott suffered from gum disease. It is unknown from the film if this condition badly affected his embouchure, and thus, his playing. A dentist recommended a radical solution: pulling all his teeth and securing a full set of dental implants. Was it the painful, drawn-out procedures that made playing at the top of his form impossible, or did the dental surgery merely fail to fix Scott’s previous difficulties? It’s not clear. (And the director did not answer my emailed question on this issue.) In any case, the surgeries failed and the pain continued. After two years away from the stage, Scott had scheduled a comeback gig at his club in late December 1996. Two days before the gig, he swallowed, with alcohol, a massive number of barbiturates, pills provided by his friendly dentist. The coroner politely called it an “incautious” ingestion, bestowing upon Scott the posthumous favor of vagueness. Yet suicide was a subject Scott had mentioned to intimates, and seemingly tried before. The film allows the viewer to assume the answer. “Depression is a very selfish disease, thinking you are only a burden,” said his daughter, Rebecca Scott, who believed the entire idea of the surgery was tragically misguided: one just can’t mess around with a saxophonist’s precious embouchure. Scott’s girlfriend, Françoise Venet, agreed.

As one player says: jazz IS life. For Scott it was more than passion; it was, apparently, a desperate need. Was it purely play well or die? The only cure for depressive pain? Is that the key, or is it an easy answer?

Scott’s death sneaks up on the viewer. Suddenly, we realize we are not seeing just another London street scene, but his funeral procession — the hearse decorated with a gigantic, whimsical saxophone sculpture on its roof. The incomparable tenor sax of Ben Webster provides the scene’s soundtrack. The song is “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” with Webster’s tremulous prayerful drama allowing us to think of heaven. It reminds us of the surpassing awe in Scott’s voice when he talked of the thrill of witnessing the legendary Webster playing his very own club.

Director Oliver Murray had little choice but to create a bifurcated film. The last half-hour digs into Scott’s difficulties, as it needed to. If this search were introduced sooner, it would have overwhelmed the contented tale of a jazz club’s unlikely survival. As it stands, the film leaves one with the sort of mournful questioning an arty film of fiction might produce. Luck, love, friendship, and talent apparently weren’t enough for Scott. He was that fragile. But the now world-famous Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club remains on Frith Street to this day, a quarter-century after its founder’s death. We see the club thriving under the next generation of owners. While Ronnie Scott’s psyche remains a mystery, the joy he gave the public is certain.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

I am Françoise Venet, the lady Ronnie Scott spent most of his life with, over 12 years.

I am heard only briefly in the film as most of the interview was cut off.

I can tell you that Mary Scott never was married to Ronnie, only lived shortly

with him and left him with the baby for the USA. Her name is not Mary, nor Scott,

only used the name because of the child.

I was the first person interviewed for the film, to which I agreed as long as it was to be

about Ronnie, the man, not the Club. I was sorry it all got changed along the way because not much at all was said about Ronnie, the most fantastic an ever.

I’ve watched this several times since it’s release. What a remarkable man he was. Thank you for clearing up some questions.