Book Review: “All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days” — Innovative History of a Female Anti-Nazi Resistance Leader

By Helen Epstein

What holds this wildly ambitious book together and drives the narrative is Rebecca Donner’s unwavering, partisan voice.

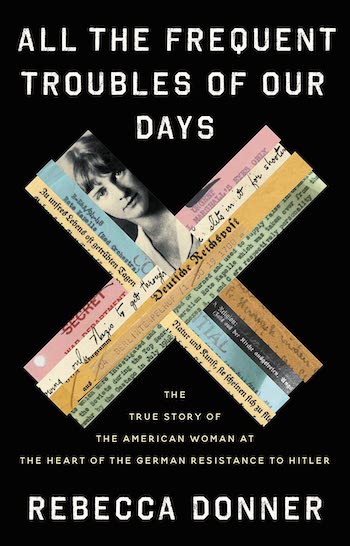

All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days: The True Story of the American Woman at the Heart of the German Resistance to Hitler by Rebecca Donner. Little, Brown, 576 pp., $32.

“The recognition that many Germans supported Hitler often leaves little room for stories about those who opposed him,” writes Rebecca Donner in this boldly structured, deeply personal, and deeply researched biography. Its heroine is the author’s great-great-aunt Mildred Fish Harnack (1902-1943), a Milwaukee-born literature professor, fiercely anti-Nazi resistance leader, and the only American woman to have been guillotined by personal order of Adolf Hitler.

“The recognition that many Germans supported Hitler often leaves little room for stories about those who opposed him,” writes Rebecca Donner in this boldly structured, deeply personal, and deeply researched biography. Its heroine is the author’s great-great-aunt Mildred Fish Harnack (1902-1943), a Milwaukee-born literature professor, fiercely anti-Nazi resistance leader, and the only American woman to have been guillotined by personal order of Adolf Hitler.

I had never heard of Mildred Fish Harnack. But, as Donner points out in her introduction, “Her aim was self-erasure.” Given that intention, compounded by the long neglect of women by world historians, the long classification of Nazi-era documents during the Cold War, and the vagaries of the publishing industry, this extraordinary woman is barely known today.

In 2002, Shareen Blair Brysac published Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra, an initial and more conventional biography of the provincial Midwestern girl who was decapitated by the Nazis. While that book lay much of the groundwork for Donner, it does not provide the thrilling narrative that Donner has written. Her book makes you sit up and think about how few innovative authors are writing history today.

Donner clarifies right off that she has adhered to the rules of nonfiction while employing many of the techniques of a novelist. She opens with the first of many photocopied fragments in the book: a questionnaire from Plotzensee Prison, February 16, 1943, which lists Mildred’s meager assets and the charge, “Accomplice in treason.” That’s followed by a short author’s intro, then a scene of an 11-year-old boy in 1939, working as Mildred’s courier. The juxtaposition of bits of print, records, photographs, notes, descriptions of an enormous group of people, and a large number of documents — all embedded in a narrative chopped into short numbered texts — gives the book a rough texture and a jumpy forward propulsion.

What holds this wildly ambitious book together and drives the narrative is Donner’s unwavering, partisan voice. She’s bent on writing Mildred back into history and she chooses to do it almost entirely in the present tense. “On July 29, 1932, Mildred exits the U-Bahn station and heads north on Friedrichstrasse, a leather satchel in her grip. It’s Friday. She’s on her way to the University of Berlin where she lectures twice a week. Her pace is brisk.… the sidewalks are clogged with pedestrians.… Mainly poor. Begging, sleeping, fighting, selling shoelaces, scraps of newspaper, passing between them cigarette butts scrounged from a gutter.”

Instead of long traditional chapters, there are short — some super-short — sections with edgy headings like “Lunch Before Kristallnacht” “Bye Bye Treaty of Versailles,” or “Knock Knock,” that shatter the years between 1932 and 1943 into jagged pieces. Lists and short, simple sentences such as “In 1928, the Nazi Party got less than 3 per cent of the vote in a Reichstag election. In 1930, it got 18 per cent. In 1932, it gets 37 percent” lend the narrative the odd quality of a schoolbook. But that also supplies an Edward R. Murrow-like sense of “You are there.”

Donner summarizes Mildred’s first 30 years in a few pithy pages. She was born in a Milwaukee boardinghouse, the fourth child of a lower middle-class family. Her ne’er-do-well father, William Fish, moved the family whenever he couldn’t pay the rent — almost every year. Her mother, Georgina, a high-school dropout, taught herself shorthand and worked as a secretary. Mildred’s oldest sister left home for Madison, where she obtained a degree at the University of Wisconsin. Mildred and her mother followed her there and then to Chevy Chase, MD. Mildred attended American University before transferring to the University of Wisconsin. There she obtained two degrees and, in 1926, married Arvid Harnack, a German lawyer and doctoral student in philosophy. In 1930, they moved to Berlin where she was briefly a professor of English and American literature (Emerson and Whitman were her favorite writers). When the political situation worsened and she was fired, she found a job in 1932 — the only woman on the faculty — as teacher in Berlin’s first evening school for working class adults. That year she hosted her first clandestine meeting, which will come to be called The Circle. “Some members are Mildred’s students. Some are friends. Some are friends of friends. They are factory workers and writers, lawyers and professors. They are Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, atheist.” Some are Communists. Some are Social Democrats.

After that whirlwind backgrounder, Donner focuses almost entirely, chronologically, on the years 1932-1943 in Berlin. That’s smart because, even though time and place are strictly delimited, her cast of characters is huge. At the center are Mildred and Arvid: tall, blond, blue-eyed prototypes of Hitler’s Aryans. They interact with three major groups: the Nazis, the Americans, and the international group of resisters.

Donner writes about Nazis when their actions impact Mildred. She cherry-picks details for the reader, pursuing themes that interest her and backing them up with descriptions, quotes, dialogue, and anecdotes from documents, minutes of official meetings, newspaper reports, letters, diaries, memoirs, and biographies. One of her most moving and consistently revealing sources is Mildred’s correspondence with her mother.

“In letters to her mother,” Donner writes, “Mildred writes plainly and simply, knowing that Georgina Fish’s tenth grade education hasn’t prepared her for the complexities of German politics. ‘There is a large group of people here which, feeling the wrongness of the situation — their own poverty or danger of poverty — leads to the conclusion that, since things were better before, it would be a good idea to have a more absolute government again.’ She explains that the term Nazi stands for National Socialist German Workers’ Party “although it has nothing to do with socialism and the name itself is a lie. It thinks of itself as high moral and like the Ku Klux Klan makes a campaign of hatred against the Jews.”

Donner seems aware that, 100 years after the rise of Nazism, she must explain basic information for her general reader in much the same way Mildred did for her mother — but without oversimplifying and alienating those better informed.

Mildred Fish Harnack– the only American woman to have been guillotined by personal order of Adolf Hitler.

The book’s collage of Mildred in her apartment, statistics about Germany’s media mix in 1933, and a mini-profile of Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels are a good example of Donner’s approach. “Once,” she writes, “Goebbels aspired to be a writer.” He earned a doctorate, wrote plays and a novel, and tried vainly to get a newspaper job. It was only when he met Hitler that his luck changed. When Goebbels became Minister, Germany had more newspapers — 4700 weeklies and dailies — than any other industrialized nation, with 90 in Berlin alone. Donner continues: “Goebbels wastes no time in setting up seven departments to oversee Germany’s newspapers, film, radio, music, visual arts, theater, and literature.” Concerned with repeating Hitler’s core messages into every household in the country, he hit upon the idea of a People’s Radio that every German could afford and that had only a limited national range, cutting German citizens off from the rest of the world. She quotes Goebbels that August: It would not have been possible for us to take power or to use it in the way we have without the radio.

“Mildred doesn’t own a People’s Radio and never will,” Donner explains. “The radio she listens to is a Blaupunkt.… Its shortwave reception enables it to pick up foreign news broadcasts. Radio programs produced in other countries are quickly becoming the only reliable sources of news.”

The second large group of characters in All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days are the Americans in Berlin. They include Mildred’s friend Martha Dodd, socialite and eventual Soviet spy; her father, William Dodd, the American Ambassador (“Henry Morgenthau’s Man”), and American spy Donald Heath, his wife Louise, and their preteen son Donald Jr., who serves Mildred as a courier. There are also cameo appearances by a range of tourists in Berlin, including novelist Thomas Wolfe.

The third, largest, and most unfamiliar group to the reader are the resisters themselves, ranging from the mostly working-class members of Mildred’s Circle to an aristocratic Who’s Who of the anti-Nazi German establishment, including members of the Harnack, Bonhoffer, Delbruck, and von Dohnanyi families. They smuggle messages, hide fugitives from the Nazis, help Jews escape, print posters and leaflets (in 1936, Donner writes, the Gestapo collects 1,643,200 anti-Nazi leaflets), and maintain contact with Soviet and Western diplomats.

For the most part, Donner does not spell out the details of their political affiliation. She makes clear, however, that Mildred and Arvid met in left-wing circles back in Madison and that by 1935, Arvid Harnack had been officially recruited as a Soviet spy.

One of the attractions of Donner’s history for me is the number of women she writes about, a heterogeneous group that includes names unknown to an American reader, such as Greta Kuckoff, Gertrud Klapputh, Emmi Bonhoeffer, Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Mildred’s mother Georgina Fish, niece Jane, and angry sister Harriet, who disapproved of Mildred’s politics and tried to destroy all evidence of Mildred’s resistance activities.

The many important men — from Hitler to Arvid Harnack — are relegated to the background. Mildred is front and center as she studies, teaches, lectures, networks, and recruits. She has an abortion; she has a miscarriage. She builds up her Nazi cred by joining a Nazi teacher’s union and the Berlin chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, presiding over the American Women’s Club in Berlin. When she returns to the US in 1937 on a lecture tour and to see her mother, who is dying, her family and friends find Mildred to be strange, jittery, paranoid. Thirty-four and childless, she is like no one else in her family. Some see her as a Red; others as a Nazi. She confides in no one.

Arvid and Mildred were arrested on September 6, 1942, as they were trying to flee Germany. On February 16, 1943, Mildred was beheaded, after copying out and translating into English the line of the Goethe poem that is the title of this book. Arvid had been hanged two months earlier.

As someone who is disappointed by much contemporary nonfiction, I found All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days to be a thrilling, if demanding, read. This is the best kind of nonfiction. It reads as though the author’s life depended on it.

Helen Epstein (helenepstein.com) is the author of the books of non-fiction and of the forthcoming memoir Getting Through It: My Year of Cancer during Covid.

Tagged: All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days, Helen Epstein, Mildred Fish Harnack, Nazi, hitler

Am reading the book and can’t put it down. Angry that life is interrupting my reading time. So well written. I am an Army vet and VN vet and my father a WWII vet. So the book gives me pause about what these people went through. So concerned that the present generation of young people have no idea of all that went before them. They have no clue. I can say now, half way thru this book and will not want it to end. Oooh rah…..