Book Review: “About Time” — Clocks That Made History

By Allen Michie

David Rooney’s thesis in About Time is provocatively ironic: clocks, through their ever-increasing precision and regularity, are the instruments of constant change.

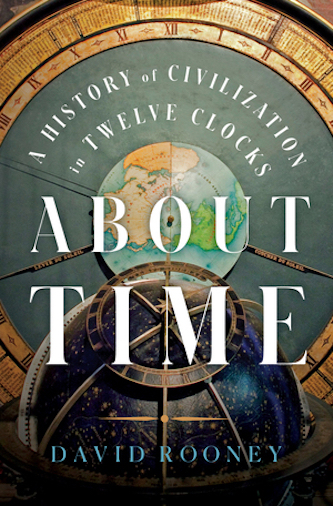

About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks by David Rooney. W.W.Norton, 288 pages, $18.95 (paperback).

Do you have time to read this review? How do you know?

You are either at work, and you may be “stealing” time. Or perhaps you’re reading this over breakfast before work, when the amount of time you have has a sharp cutoff. Or you’re reading this in the evening, during that sliver of time between work and having dinner, or having dinner and doing the dishes, or doing the dishes and going to bed. Or you’re reading this over the weekend, an invention of the labor unions who negotiated with governments for us to have 28.57 percent of the week to ourselves. In any of these cases, or related ones, your time is not wholly your own. Your time has been apportioned, allotted, conceived, controlled, and enforced by powers and people outside your control.

No matter when you’re reading this text, the words are on a charged-up computer, a smart phone, or a tablet device that knows exactly what time it is. Those subtle numbers in the corner never let you forget. It also likely knows exactly where you are, when you began reading this web page, and when you’ll finish. The Arts Fuse can download a report of how many people read this review, where they were, how long they spent reading, whether they made it to the end of the page, and — of course — how long they took.

All of this is possible because of 74 Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites, each with three to four atomic clocks on board. The clocks are unassuming little black cubes, about four inches square, where electrons pass through tubes of radio waves and jump between energy states. They are accurate to within one second every 158 million years. (New clocks are in development that will be accurate to within one second every 30 billion years — more than twice the age of the universe.) GPS knows where you are not because it triangulates distances, but because it measures time signals and compares the infinitesimally small differences between different clocks on different satellites. It can calculate a position to within 10 millimeters (the length of your little fingernail). Your “smart” electric grid that charged the reading device you’re looking at now relies on measuring equipment that is synchronized to within a billionth of a second, from signals sent by those little Rubik’s Cubes of the space-time continuum out in the blackness of space.

All of this isn’t really about time. Time, in the words of Doctor Who, is “a big ball of wibbly wobbly, timey wimey stuff” that Einstein proved was relative and curvable. What controls our lives with so much precision and iron law isn’t the message, it’s the messenger. It’s the clocks.

David Rooney’s thesis in About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks is provocatively ironic: clocks, through their ever-increasing precision and regularity, are the instruments of constant change. “With clocks, the elites wield power, make money, govern citizens and control lives. And sometimes, also with clocks, people fight back. None of this is abstract. These are real clocks with recoverable histories that bring pivotal and sometimes violent moments from the past vividly to life.”

The book is organized around 12 of these real clocks, from different eras and parts of the world, from the sundial at the Roman Forum in 263 BCE to the miniature atomic clocks in outer space bringing you this article right now. The 12 clocks in the 12 chapters are conversation-starters, but each chapter also centers on an idea: order, faith, virtue, markets, knowledge, empires, manufacture, morality, resistance, identity, war, and peace. Within each chapter, you’ll find many more clocks, both famous and obscure, each ticking away at a fractal view of history that finds the macroscopic contained in the microscopic.

The The clocks are not just symbols. It’s a revelation to learn how central and important the clocks were. The chapter on empire, for example, chronicles how navigation at sea led to global trade, which led to global empires. It’s no exaggeration to say that the entirety of the British Empire depended upon finding a way to calculate longitude. The solution was sketched out by the Dutch, who knew that high noon in Cape town was 3:37 different from high noon in Mumbai. One hour of time difference equals 15 degrees of longitude, so you can find your place at sea if you can compare your time where you are relative to the time at a fixed place at port. Makeshift sundials could identify high noon while at sea. Unreliable clocks could be adjusted from there. At ports, such as Cape Town, cannons were fired at exactly noon every day. They could be heard for miles, allowing sailors to measure the difference on their clocks (essentially the same idea, updated just a bit, behind GPS). By the late 1750s, the British had made a close-enough mechanical chronometer. That device, combined with accurate cosmological charts to track the distance of the moon, made it possible to calculate longitude. No longer would ships aim at the Carolinas and be happy if they landed in Massachusetts: the British Empire could set sail. (Other nations still relied on time signals from shore — flags, cannons, guns, balls, and discs — through 1910.)

Rooney, eminently qualified for this project as a former curator of Timekeeping at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich and the curator of several clock and watch museums, reveals some astonishing chains of cause-and-effect. To semirandomly pick just one of the many examples, it used to be commonplace for each town in England to keep its own separate time (which strikes me as quintessentially British). “The local time at Bristol according to the Sun is ten minutes behind Greenwich.” But with the 1830s came trains. Unless you changed your watch at every station, there was no way to know exactly when your train would depart or arrive. (More important, no way the conductor could know how to avoid another train heading in the opposite direction on the same track.) Enter Greenwich Mean Time, where a single clock could simultaneously send a time signal across the new telegraph wires to every train station in England. Once central time was established, pubs across the country started using the same last-call times, to the delight of the Victorian anti-alcohol reformers. Factory workers began working by the clock, not by the job. One moral reformer, William Willett, effectively argued that daylight was good for the body and soul. After a good deal of political wrangling, Daylight Saving Time (known as British Summer Time in the UK) was invented solely to give us an extra hour of it. “It is a splendid thing for every man in summer to get back to his home in time to look after his little garden, or whatever his particular hobby might be, after his day’s work,” wrote Arthur Conan Doyle, a supporter of the plan.

A recurring point made in the book is that clocks transform time itself — supposedly a global constant based on the rotation of the Earth around the Sun — into a series of political (and sometimes theological) decisions. North Korea is literally behind the times — in 2015, they moved their clocks 30 minutes behind those of their neighbors in South Korea. (They blamed the Japanese imperialists.) In 2007, Hugo Chávez also set the clocks back 30 minutes in order to create his own time zone and reinforce Venezuela’s political identity. (Maduro changed them back nine years later, somehow claiming it would save electricity.) The latest cuckoo clock fight was in London, as the Brexit and anti-Brexit proponents created a huge symbolic culture war battle over whether the scaffolding covering Big Ben, under renovation, should be removed so it could strike the exact hour when Britain left the European Union. “Big Ben should bong for Brexit!” exclaimed Mark Francois on the floor of the House of Commons.

Author David Rooney

Sometimes the symbolism of clocks is artistic, whimsical, or nostalgically nationalistic. There are also instances where clocks are used as blunt instruments of raw power or dominance. There was something of a chronometer arms race throughout medieval Europe and the Middle East for churches to demonstrate not only God’s perfect order and wisdom, but also to remind you of your tiny place in the universe and the state’s role in enforcing both. The engineering was often incredibly ingenious, and the best clock makers were courted by city governments like rock stars. Before electricity and computer chips, clocks were driven by dropping balls, springs, sticks of incense burning down, water or sand dripping, and of course people winding the gears and pulling the ropes. The Castle Clock of al-Jazari, in today’s Turkey, was a marvel in 1206 (1206!): “At daybreak, the crescent Moon would start to move imperceptibly in front of the lines of twelve doors, at a speed of one pair of doors per solar hour. As each pair was passed, the upper door would open to reveal a human figure…. The two falcons would lean forward, raising their wings and lowering their tails, each dropping a ball from its beak into the vase below to strike the cymbal.” At night, oil lamps would slowly fill by the hour, and once fully illuminated, mechanical musicians would blow trumpets. There are too many other examples of the magnificent ancient clocks and astrolabes around the world to mention (although I absolutely must mention the breathtaking one still functioning in the city center at Prague), some of them lost to us now. Rooney’s appreciative and informed enthusiasm for them will keep you daydreaming.

Moving abruptly to our own time, the real jaw-dropper is the chapter about markets. It reads like science fiction (utopian or dystopian, depending on how you feel about capitalism). We are accustomed to thinking about time in the largest possible scales — the distant past, the far future, infinity — but the stock market deals with time in the minutest increments. A vast majority of stock market trades are now computerized, triggered by a maze of different market conditions. Each trade must have a very precise time stamp. Back in the day, there was a big clock on the tower of the trading plaza, as in the Amsterdam stock exchange in 1614, or on the wall of the stock market trading room, like the one in the London Stock Exchange in the 1830s. But today demands something more expansive: “What about the thousands of computer servers exchanging high-frequency trades around the world? Each server, each microprocessor, each network switch needs to have access to the same clock, somehow.”

The technology took off fast and is still improving (if that’s the right word for the surreal atom-splitting going on here). The European standard now is for trades to not deviate from the accepted UTC baseline by more than one-millionth of a second. If auditors find a discrepancy, firms can be fined 10 percent of their global revenue. (“Not profit — revenue.”) Rooney does some detective work: he travels to London, gets cleared with security, and doesn’t stop until he can lay eyes on the physical computer clocks that can do this. Two refrigerator-sized hydrogen maser clocks in a nondescript office building in Teddington link to two backup pairs that connect to an ensemble of atomic clocks that connect to fiber links that connect to an identical pair of clocks in a steel cabinet buried in the another building, that connect to the cables leading to everyone around the world who subscribes to the service. (Alas, there are no mechanical musicians blowing trumpets.) This is not your grandparents’ dial-up phone time service. There’s a great chapter on that, too, by the way. The voice of the lady who first read the time over the phone was chosen for her sex appeal to help expand the telephone industry into private homes.

“In every civilization, and throughout time, we have encountered clocks that people have made to advance some sort of goal,” Rooney concludes. “A wider goal than simply measuring time. Or, rather, we have found that all clocks have been made to do this. Every single clock in history.” That includes the clock strapped to your body right now, and the clock looking back at you on the screen where you’re reading this sentence right now. About Time asks us to consider, with the widest perspective of history, what the goals of these little numbers are. And what your goals are. And whether they are synchronized.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, TX.

Tagged: About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks, Allen Michie

Interesting. One thing I must say though, is that clocks don’t measure time-they create it. There are gaps between events, but each event doesn’t happen in “time.” It happens now.