Arts Commentary: Separating the Maker from the Made, the Doer from the Doing

By Steve Provizer

It is natural to believe that there is (or should be) a close connection between the personality and the work.

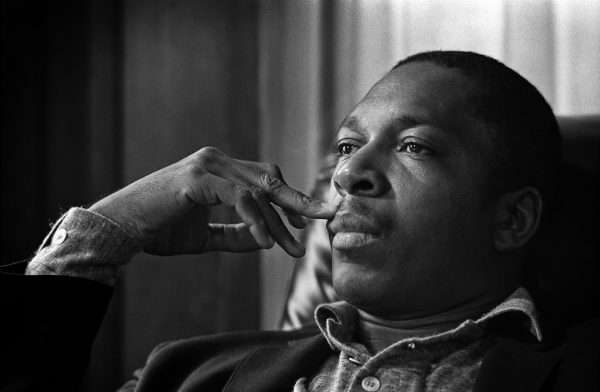

John Coltrane. Photo: Jim Marshall Photography LLC

The more I thought about the ideas I explored in my review of Erich Hatala Matthes’s Drawing the Line: What to Do With the Work of Immoral Artists From Museums to the Movies, the more sympathetic I became with the author’s task. Separating the art from the artist is a fractal question, with new complications arising at every turn. One thing did become clear during my investigation, however: humanity’s need to exercise creativity and imagination — to achieve something beyond mere survival — is universal. Separating the maker from the made, the performer from the performance, raises issues that extend far beyond the world of art.

Fewer people contemplate the value of art than they do the pleasures of sports, cars, science, haute cuisine, or scores of other pastimes. Yet the latter areas come with their own connections to proportion, tension, release, and other “artistic” processes. They too offer us chances to experience the joy and awe that’s inspired by watching, reading, or listening to those performing at the highest level of excellence. I would defy any cognitive psychologist to tell me which MRI brain scan was triggered by a Lamborghini, a Modigliani or a Penny Black stamp.

This observation might ruffle the feathers of those who hold that the “sophisticated” aesthetic rewards of art are qualitatively different from those provided by other pastimes. (Note: the creators of “high” art are no less prone to moral transgressions than the creators of “low” art.) But the fact is that connoisseurship — or snobbery, if you will — can be found in almost all of the areas I have mentioned. Basketball fans differentiate between a team that grinds in the low post versus one that plays its game above the rim or relies on fast breaks. Car lovers argue about how to evaluate the look and utility of “spoilers” on non-sports cars. These choices are in the same category as picking which band’s logo will be on your T-shirt — a declaration of what tribe you chose to belong to.

These fields of endeavor share a common denominator. A sublime performance, a profound poem, or a beautiful object represents a flash of intuition about why life might be worthwhile, as is something as elemental as laughter or a dance step. They represent the possibility of transcending our quotidian life and offer us a precious respite from thoughts of our inexorable demise. And, while performing may be the most direct way to achieve this feeling, these encounters are no less vital because they are vicarious. The feelings, perceptions, and emotions that arise in any of these exchanges can be as intimate as any other in a person’s life. In fact, when you look closely, it’s clear they’re associated with the twin poles of love and hate. Love is not a word that people are afraid to use when they refer to a prized bonsai, Braque print, or pet bulldog. Nor is the word hate, in response to being betrayed by anyone whose work you love. These relationships can cut so deeply that, when they disappoint, they can undermine the idea that opening oneself up to emotional vulnerability is a healthy life strategy.

It is natural to believe that there is (or should be) a close connection between the personality and the work. This instinct remains pervasive despite the fact that “nice” people sometimes produce disturbing, violent work and people who produce beautiful, serene, pastoral work may be pursued by demons in their personal life. The truth is, analyzing the psychological links between work and worker is fraught. An authoritative biography might provide some clarity, but transparency is an illusion — much of what we know about creators is an ad hoc mixture of information, gossip, and exaggeration.

So, the kind of moral choices faced by fans of Tiger Woods (sexual addiction), Michael Vick (dog fighting), and Erwin Schrödinger (pedophilia) are inevitably similar to those grappled with by followers of Michael Jackson, Woody Allen, or Roseanne Barr. Each case comes with variables and ambiguities. One of my few personal heroes is John Coltrane. But what if I had been around him during the years that the saxophonist was an addict? If I saw him in 1955 — dressed sloppily and nodding off on stage — would I have given up on him? Does Clifford Brown’s spotless personal reputation mean that I tend to elevate his playing above that of, say Lee Morgan, whose reputation is far cloudier?

The question remains difficult no matter how carefully and self-consciously we approach it. As we watch, listen, or read, sensations and emotions arise in our body. Our mind works on deciphering and analyzing the event, object, or music, while our consciousness observes all of this unfold. Perhaps if we knew ourselves more completely, we might be able to disentangle the ineffable way our view of the artist/maker/performer arises from this matrix. Until then, uncertainty is our fate. Most of the time, that is a reasonable price to pay for the experiences that make life worth living.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.