Film Review: “Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” — Satiric Fury, with a Dry Midwestern Chuckle

By Matt Hanson

The documentary supplies plenty of deserved admiration for its haggard but gentle subject, but it doesn’t tell us enough about the enduring value of Kurt Vonnegut’s writing.

Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, directed by Robert B. Weide and Don Argott. Available VOD.

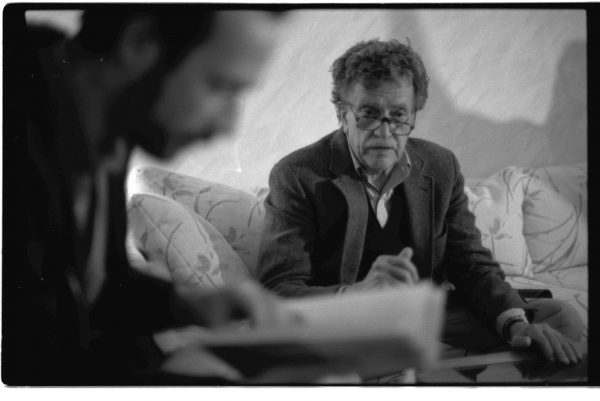

A scene from Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time: Kurt Vonnegut and director Robert B. Weide. Photo: Minnick and B Plus Prods/IFC Films.

Kurt Vonnegut is listed as “sad man on street” in the IMDB page for the film adaptation of his great novel Mother Night. An appropriately comic/melancholic summary of an American writer who could credibly be described to have been through it all. His novels, plays, and nonfiction reflected a “seen it all” attitude, a wised-up vision of the “way things are” conveyed with a plainspoken honesty that cackled with moral outrage. It is no accident that his books (along with John Steinbeck’s, for some reason) are the ones strangers recommend to me when they notice me reading in public.

Robert Weide, director most notably of Curb Your Enthusiasm and the aforementioned Mother Night, has recently released Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, a documentary about the author that was thirty-three years in the making. Weide’s often harrowing tale of Vonnegut’s life — and the filmmaker’s connection to him as a person — is focused, genuine, and moving. Still, amid the obvious and well-deserved affection for its subject, the documentary misses making a case for what makes his writing and general worldview necessary.

We are taken through Vonnegut’s sprawling home in Indiana. Craggy but sentimental, the author explains how his loving, boisterous family was wounded by premature death, mental illness, and economic precarity. If you’re already one of his many fans, you know the story of his service in World War II and how Vonnegut was captured and held prisoner in a Dresden meat locker while the Allies bombed the cultivated city to smithereens, a searing trauma he — like most of his generation — never discussed. You should hear it again anyway. It took him many years and discarded drafts to arrive at the proper structure and tone for Slaughterhouse Five, which was a massive hit in 1969. It came at an appropriate time during the Vietnam era — a growing segment of the reading public, skeptical of the morality of combat, relished having conventional war narratives mocked.

Weide is very good at showing us what it was like for Vonnegut to return to normalcy after the war. Working odd jobs, including selling cars and writing corporate copy, the writer’s experience supplies an unexpectedly nostalgic look at the days when a young literary type could scramble together a living though his pen, supporting a family by writing short stories for the glossies. If he could place but five tales, a young and ambitious Vonnegut calculated, he could finally quit his stupid day job and write full time. Those days, of course, have gone the way of the dodo.

Significantly, Weide makes it clear that the most important factor in Vonnegut’s life and work, aside from his talent and available markets for fiction, was the unstinting devotion of his first wife Jane Marie Cox. She gave him The Brothers Karamazov to read on their honeymoon; she believed in his genius completely and unswervingly. Jane handled the homestead while Vonnegut sat in an eye-stinging haze of Pall Mall smoke, elevator music blaring from the radio, and banged out fiction on his typewriter. Incredibly, her children explain that she didn’t even seem to be all that bothered when he eventually left her for the photographer Jill Krementz, who is barely mentioned in the documentary.

The Vonneguts already had children of their own when they adopted the writer’s four bumptious nephews after his beloved sister died prematurely. This was a very noble, if frazzling, decision for a struggling wordsmith. The kids all seem to have made it out of their zany childhood on Cape Cod with sanity intact. They speak warmly of their parents, though Vonnegut’s mood alternated between somber or joyful, depending on how the morning’s writing had gone. Home movies display Vonnegut’s goofy sense of humor and his obvious affection for his children. But linger on the haunted look in his eyes — it’s clear that the man knew a thing or two about the murkier parts of the human condition.

“So it goes” is Slaughterhouse Five‘s commonly quoted refrain; this attitude of passivity before the enormity of human suffering is elaborated on in his other books. It’s a deceptively blithe way to be stoic in the face of the world’s consistent waves of tragedy and suffering. It’s funny precisely because it responds to disaster with a dry Midwestern chuckle, which is an essential part of Vonnegut’s style as writer and person.

Kurt Vonnegut and director Robert B. Weide in Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time. Photo: Minnick and B Plus Prods/IFC Films.

But this stance of resignation shouldn’t come lightly and isn’t for amateurs — being this irreverent has to be earned when the stakes are that high. An attitude of nonchalance about catastrophe comes perilously close to an apathy and narcissism that the resolutely humane and idealistic Vonnegut abhorred. If you are going to proclaim (perhaps satirically?) that “we were put on earth to fart around. And don’t let anybody tell you different” there has to be the gravitas of a lived life to back it up. Vonnegut had that.

At one point, Weide quotes a passage from Breakfast of Champions about how 1492 was, contrary to the standard account, not the year that America was “discovered”: “Actually, millions of human beings were already living full and imaginative lives on the continent in 1492. That was simply the year in which the sea pirates began to cheat and rob and kill them.” He praises the observation by saying that any high school kid would immediately fall in love with someone who could write like that. And yes, doesn’t everyone love the thrill of subversion when they’re young? Keeping it going when you get older is the important thing. Still, there is something not quite right here: isn’t there more to Vonnegut’s importance as a writer than assuaging an urge for rebellion?

Here is where Weide, perhaps unintentionally, comes up short. He misses Vonnegut’s stubborn sense of injustice, a philosophical and political demand for fairness that drove his indignant satire. His acid wit was a coping mechanism, a defense against being overwhelmed by his disgust with the savagery of humanity. Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time amply demonstrates the author’s admirable personal qualities: how he never let himself become comfortable or complacent after he achieved success and fame. Unlike Mark Twain, with whom he is sometimes compared, Vonnegut never gave way to nihilism, never stopped calling out the lies, cruelty, dogma, and selfishness of the powerful right up to his final wheeze. Weide supplies plenty of deserved admiration for its haggard but gentle subject, but he doesn’t tell us enough about the writing he dedicated his life to, and which inspired such a labor of love in the first place.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.