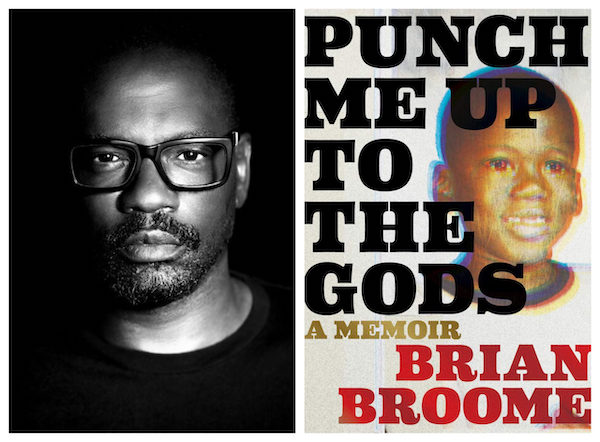

Book Review: “Punch Me Up to the Gods” — Stories That Need to be Told

By Vincent Czyz

A stunning indictment of homophobia, racism, and toxic masculinity, particularly among African Americans, Punch Me Up to the Gods holds a mirror up to America, a mirror before which many of us will not want to linger. But all of us should stare into it for as long as we can stand it.

Punch Me Up to the Gods by Brian Broome. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 250 pages. $26.

Brian Broome’s Punch Me Up to the Gods is not a memoir in the traditional sense. If you want to know what he does (or has done) for a living, what his brother’s name is (or his sister’s), if you want a clear chronology or even a continuous storyline studded with the events in his life, you’re going to be disappointed. If, however, you want to share in the pain and humanity of a man who happens to Black and gay, who grew up in a small Midwestern town that made both of those things inordinately difficult, who writes eloquently and movingly about some of his most intimate moments, if you want some notion of the lengths to which a human being will go to feel loved — to feel a sense of belonging — you should put a visit to your favorite bookstore on your to-do list.

The book opens with Broome watching his own life being reprised by a young Black father and his son Tuan. After the toddler takes a nasty fall on the sidewalk, his father has no words of sympathy, no comforting hug. Instead, he’s annoyed by the boy’s wailing. “‘Shake it off, Tuan,’ the young father says” before “turning back to his phone.” All of about three, Tuan isn’t allowed to cry or show pain. “‘Be a man, Tuan,’ the boy’s father says … eyes steady on the phone.”

“I remember,” Broome recounts, “how my own tears were seen as an affront, as if I were leaking gasoline and about to set the whole concept of Black manhood on fire.” Broome was “a clay that [his father] molded not with fingers but with punches.” The beatings were administered as much to punish him as to toughen him up for a world that, his father warned, would show him no compassion — indeed, one in which whites would exult in his suffering. Chillingly, his father tells Broome he’d rather kill him himself “than see white people do it.”

Broome, who was born in 1970 in Warren, OH, a small town soon to become part of the Rust Belt, skips his own toddlerhood and goes right to age 10, the age at which he realized he was not cool: “Couldn’t summon it. Couldn’t fake it.” His best friend, Corey, who was loaded with cool, reinforces the lessons Broome’s father dispensed: “White boys could just do whatever. But Black boys had to show through our behavior that we were undeniably, incontrovertibly the most male. The toughest.”

The next sentence explains a great deal of the angst Broome was to experience throughout his adolescence: “We sat on either end of his bed, and I got lost in his pretty brown eyes as he explained that white boys were basically girls — ‘pussies’ — and that there was nothing worse than a boy being like a girl. I stared blankly, wanting to kiss him.”

Their friendship is as dysfunctional as it is sad, and Broome’s attempts to cling to it culminate in one of the more appalling incidents in the book. Since Corey’s other friends have called out young Broome for acting “like a white boy and a fag,” Cory leads him to an abandoned barn where, in full view of his accusers, Broome is expected to have sex with a girl of eleven or twelve. “After she was done here, she would get whatever candy or potato chips these boys had promised her,” Broome matter-of-factly states. These two children, surrounded by a crowd of older children, drop their pants and grind their hips together. The girl has an idea of what’s supposed to happen, but Broome is at a total loss. No intercourse takes place, and Corey, disgusted, punches him in the chest so hard Broome knows the “friendship” is over.

The opening chapters lay out the basic pattern the rest of the book will follow: an interlude about Tuan, a life event in excruciating detail — often interspersed with flashbacks or cut with segments of another incident — another interlude with Tuan. The result is that Punch Me Up feels more like a stitched-together series of essays than a memoir. While it is sometimes unnecessarily disjointed, the accumulated impact of these separate incidents is enough to crater even a jaded heart.

At age 15 the mere knowledge of who he is becomes psychological torture. “I fought my demons every night,” Broome writes, “and prayed that the Good Lord would take these [homosexual] desires away from me. The Good Lord never did. In fact, He only made them worse. I abandoned all hope. I couldn’t stop and decided that hell was where I should end up.” The allusion to Dante’s infernal verses embedded in the paragraph is both apropos and subtle enough to miss on a first reading.

The angst of being gay compounded by that of being Black, Broome prays for death so he can “be reborn the right way,” that is, straight and white. Whiling away afterschool hours in front of the TV, he comes to believe “that the most important thing in life was to be liked. By everybody. Between [the TV’s] teaching at home and social life at school, I learned that the whiter you acted the better liked you were. […] I concealed every part of myself that I deemed to be too ‘Black.’” White, Broome decides, “wasn’t just a race, it was a goal.”

He finds a measure of acceptance dancing for white kids in his high school, but it comes at a cost. “The levels of coonery to which I sank were unfathomable,” Broome confesses. “I shucked and jived my way into their hearts every day in the gym after they’d had their lunch.” He garners head-shaking and glares of disapproval from the Black kids in the school, but Broome is indifferent to them. “They were doomed to be Black their whole lives. Plus, they had called me ‘faggot’ enough to earn my hatred forever. I had found acceptance. That’s all I ever wanted.”

At the Red Caboose, a nightclub for teens outside Warren, he discovers that the acceptance he longs for is illusory. When the witching hour arrives and the Caboose is closing, he has no way home. It’s a frigid winter night, but white parent after white parent refuses to let a 15-year-old Black boy, a classmate of their children, in the car. Instead, they abandon him miles from town, well after midnight. He begs a white janitor taking out the club’s trash to let him use the phone. When his mother comes for him, she has a single stinging rebuke: “Boy, don’tchu ever trust white folks again.”

The $5 it cost to get in the club was a small fortune Broome had had to borrow. Already living at the poverty line, the family sinks below it when Broome’s father loses his job at the steel mill. Every emblem of that poverty — the unheated shack his family lives in, the clothes he wears, the fluorescent pink welfare lunch card — is deeply embarrassing to Broome. He covers his shame with lies “about our ‘swimming pool,’ our ‘housekeeper,’ my ‘bedroom’” (he sleeps on the living room floor while his brother gets the couch).

He goes on lying about his life and pretending he’s someone else long after he’s an adult who’s come to terms with his homosexuality. Take the relationship with a handsome white man, a foreigner, who assumes Broome is a wonder on the basketball court. Smitten, Broome uses this presumption of Black athleticism as a foundation on which to build a whole house of lies, a house he and his new lover inhabit for a few blissful months. It ends in abject humiliation when Broome’s lover hands him a basketball and his cartoonishly clumsy performance exposes the deception.

Most of the book is taken up by Broome’s reflections on his struggles with substance abuse and his sexual liaisons, many of which, like the basketball fiasco, are unflattering to say the least. However honest, poignant, and absorbing these misadventures are, whole sides of Broome’s life get lost in their telling. We never, for example, see Broome in a healthy relationship. We never learn anything about his career path. We never find out how he extricates himself — or is extricated — from the poverty in which he grew up. Instead, he simply appears one chapter, well-dressed, spending money in hand. His sister and brother are reduced to nameless cyphers. His father gets more airtime, but while Broome admits his father is a product of the brutality visited on him by his own father, his portrayal of the man who raised him is devoid of compassion. Even when his father is on his deathbed, Broome looms over him like a moon — cold, distant, indifferent.

Because Broome was able to stop “judging her long enough to let her speak,” his mother is an exception to these elisions. In her own streetwise voice, she narrates the circumstances of a life that is hardly less heartbreaking than her son’s. It is from her that the reader, as well as Broome himself, learns why his parents, who always seemed ill-suited for one another, were trapped in a loveless marriage. “Sometimes,” she opines, “the wrong thing is the only thing.” The late-night beating she endures in an empty cemetery after she’s been caught flirting with another man is hair-raising.

Whatever the flaws in this book, it never fails to be engaging. Broome is a consummate storyteller and has an unfailing sense of the stories that need to be told. A stunning indictment of homophobia, racism, and toxic masculinity, particularly among African Americans, Punch Me Up to the Gods holds a mirror up to America, a mirror before which many of us will not want to linger. But all of us should stare into it for as long as we can stand it.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.