Poetry Review: Writer Alain Mabanckou — Taking Life Both to Heart and in Stride

By Kai Maristed

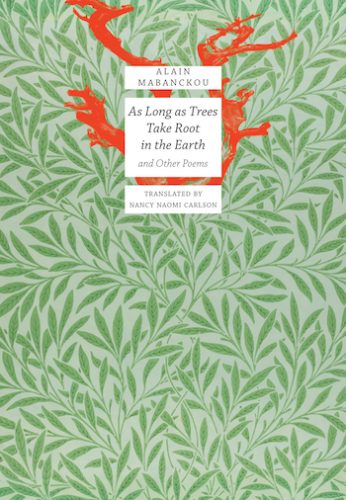

Take a dive into any of Alain Mabanckou’s works in English — and definitely score a copy of the new translation, As Long as Trees Take Root in the Earth, beautifully crafted and bound. Vive la Poesie!

Notes on the oeuvre of Alain Mabanckou, and in particular on As Long as Trees Take Root in the Earth and Other Poems, translated by Nancy Naomi Carlson. Seagull Press, 124 pages, $19.

The term “thinly veiled autobiography,” once applied to a certain type of novel, has been cleansed of pejorative nuance and reborn as “autofiction.” Going a step further in the small global literary village, the veil is often dropped completely to reveal “memoir,” which in olden days promised the distillation of a longish life but now usually consists of a long personal essay by someone in their 20s or teens. Instead of wry perspective we get solipsism concentrated like a burning glass on the author’s poor health, toxic relationships, and/or societal grievances. Instead of experience we get navel-gazing and diary grazing, bound to end either in tears or with prematurely gritted teeth. Recently in LitHub Walker Caplan offered this concise double definition: “When you write about something bad you’ve done, that’s autofiction. When you write about something bad done to you, that’s memoir.”

The term “thinly veiled autobiography,” once applied to a certain type of novel, has been cleansed of pejorative nuance and reborn as “autofiction.” Going a step further in the small global literary village, the veil is often dropped completely to reveal “memoir,” which in olden days promised the distillation of a longish life but now usually consists of a long personal essay by someone in their 20s or teens. Instead of wry perspective we get solipsism concentrated like a burning glass on the author’s poor health, toxic relationships, and/or societal grievances. Instead of experience we get navel-gazing and diary grazing, bound to end either in tears or with prematurely gritted teeth. Recently in LitHub Walker Caplan offered this concise double definition: “When you write about something bad you’ve done, that’s autofiction. When you write about something bad done to you, that’s memoir.”

Fortunately, imagined novels — an alchemy of personal experience, themes beyond self, and the dream-state of “what-if” — still happen too. In As Long as Trees Take Root in the Earth, the prolific and, in France, highly popular Congolese-French novelist and poet Alain Mabanckou puts it this way:

You think you are writing

but time forces

the hand into motion

shadows blur sight

murmurs haunt hearing

til the mind

capitulates

Poetry, from Li-Bai to Eileen Myles, has always felt more at home in the confessional, epic Homer et al. notwithstanding. But starting more than a century ago, poets in droves abandoned storytelling and the universe of imagination. Today, the prizewinners mostly offer autobiographical shards, vignettes, and collages of varying opacity to a shrinking public. Oddly enough for an art form, the right brain reigns. One school espouses eliminating words at random from a text and printing what’s left. Meanwhile, the elements of song (rhythm, rhyme, alliteration, versification, anything smacking of form) have been chucked overboard as cheap old tricks. All right, but where is the New? So much contemporary poetry reads like prose cut and pasted in a way that leaves lots of suggestive white on the page. Consult The Best American Poetry of 2021 for examples.

Today Alain Mabanckou holds a professorship at Stanford University, which might seem a dizzying distance in multiple senses from a working-class quartier in Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo. But Mabanckou, now in his 50s, has a way of taking life both to heart and in stride. An ambush-ready but never cruel sense of humor infuses many of his novels. The first that made me fall off the sofa laughing was Black Bazaar, a rollicking chronicle of immigrant life in Paris, available in English translation and highly recommended.

For all the honors and broad readership his fiction has earned in the Francophone world, Mabanckou is not primarily thought of, there or here, as a poet. And yet poetry was his first muse at home in the Congo, his first passion. He arrived in France on a scholarship at age 22 with the equivalent of a full manuscript under his arm, and lines from Senghor, Aimé Césaire, Jacques Prévert, Rimbaud, and others in his head.

Mabanckou the novelist, by now twice a finalist for the International Booker Prize, soon began to attract an enthusiastic readership. Mabanckou the poet, whose first collection won the prestigious Prix de la Societé des Poetes Français, continued like 98 percent of his peers to publish for a self-selected few. In 2004 he published “An Open Letter to Those Who Have Killed Poetry,” writing that

“The song is familiar now: the audience for poetry has evaporated…. Nothing left for us to do but compose, in alexandrines rich with rhyme, the funeral oration…

“Here lies Dame Poetry, Muse worshipped by Ronsard,

Hugo, U’Tamsi and the others, abandoned by her ungrateful and prodigal heirs.

A little later: “To write or publish poetry these days feels like an act of resistance, a ‘last of the Mohicans’ stance.” (The above is my own translation from the French.)

The diatribe goes on to decry the “con game” of cronyism in publishing in general (hardly a French specialty), that he finds mirrored among Black and African writers. He laments the perversion of the concept of “Negrétude,” along with the sterility of poetry ordered up and composed for the historical/political occasion. He arrives at a crucial distinction: “thought” poetry versus the poetry of inspiration.

And yet he asserts: “No, poetry is not dead.” But then where is she hiding? Surprisingly, Mabanckou hails fiction as the present refuge for writing that sings. It’s in certain stories and novels, he says, that readers now find “the last stronghold of being in all its profundity.” There, and in the work of a few poets who, although resigned to the readership drought, continue to publish in the narrowed space remaining. Clearly Alain Mabanckou sees himself among this international band of resisters.

Who can resent the migratory bird

for rising above its nest

don’t change your name

don’t change your branch

remain human until the end

as long as trees take root in the earth

Echoed in variation throughout the five books collected in a recent, more comprehensive French version of As Long as Trees…, these apparently simple lines might fairly be read as Mabanckou’s credo. With sweet economy they point up major themes in both his poetry and prose.

On the one hand, there’s the refutation of those who have accused him of “assimilationism,” and of pandering to the postcolonial establishment by embracing good writing wherever found, and by living in Paris, and now Stanford, rather than Pointe-Noire. After all, is the migratory bird to blame for its nature, for its innate urge to rise and seek fresh fields?

Alain Mabanckou in 2017. Photo: Wiki Commons.

On the other hand there is the injunction to himself: don’t renounce your origin, don’t conceal who you are, or the land and people you come from. The bird’s branch before flight, the human’s parents and forebears. Remain human and truthful until the end.

The closing phrase (slightly ominous in these days of accelerating climate change), is also an homage to the Cameroonian poet d’Almeida, who believed, pace Mabanckou, that there would be poetry “as long as trees take root in the earth.” Third element of the credo.

There’s a more personal essay on Mabanckou’s own poetic roots included in the aforementioned French edition, titled “The Woman Who Made of Me a Poet.” Anguished, intense, and disarming in turn, he tells of learning, in his tiny Paris studio, of the death of his mother back home in the Congo. He recalls her prediction at their parting six years earlier that she would never see him again. Her only child. Her awful grief. Tell me did you truly love me, eh? Already the past tense. I won’t be able to bear not seeing you again… Her comprehension and forgiveness.

Pauline Kengué was unlettered. She was life itself. “I realized I could not write another line without sensing her presence.” In the shocked emptiness of days following her death Mabanckou threw out all his previous poems. One night he lit a candle and typed a title: The Legend of Wandering. “I closed my eyes. The country was before me.” Over the next three days and nights he wrote the Legend, poem(s) that would become the first of the five connected volumes collected in the French edition as As Long as the Trees. Each book pursues an aspect of the wanderer’s experience, memory, insight, outrage, and longing. It begins:

Distance is diluted

in the geography of emergency

pain rubs shoulders with the eucalyptus trees

that rim the far-off lands

and later:

These nocturnal voices in the bush

These herds of deer

that browse along the river

These skeletons of sparrows

that cling desperately

to the lines of barbed wire

All these silhouettes

Shadows upon shadows

Lo, the naked fatherland.

(My translation, since this first volume is not part of the published book at hand.)

It’s a great gift to anglophone readers to have available now the third and fourth of the poem-series that followed Manackou’s epiphany, as well as the Open Letter, thanks to Nancy Naomi Carlson and Seagull Press. Mabanckou’s craft has no need to vaunt itself. Words are woven with a precision and economy that makes punctuation unnecessary. There is a complex simplicity to these evocative, brief messages from the wanderer, whether he is witnessing the destruction caused by African brothers fighting brothers, or remembering the life of schoolboys:

with bicycle hoops

old tyres from cars

slingshots

rubber sandals on feet

bare chests

short pants

secured by a wide strap.

Translating poetry is a quixotic endeavor. If I wasn’t always in agreement with certain word choices, I respect the impact of the overall result. More significantly, in her Translator’s Notes Nancy Naomi Carlson points out that “a subtle kind of music runs through the French texts, surfacing frequently in sound and rhythmic patterns, as well as silences. The challenge for me was to honour the original music.” It’s a challenge not completely met here, and if only because English is a far less rhymed and aurally often flat-footed language. A poet I know only warmed to Mabanckou’s lines when I read the original out loud. To have printed the poems en face in each language would have made for a richer experience.

While I don’t believe that Mabanckou had his own prose in mind when he wrote back in 2004 that poetry had found a refuge in fiction, I couldn’t help reflecting on the notion while reading one of his most recent novels, Les cigognes sont immortelles (The Storks Are Immortal). Like his poetry, this moving tale, told by a schoolboy whose life in peaceful Pointe-Noire is shattered by a political assassination, gleams with indelible images and flashes of wit. It also makes much use of phrasal echoing and repetition in the African oral style. The accumulations lend a choral effect; like waves on the Congo river they move the story along, at first slowly, then with ineluctable acceleration. (David Diop, in his 2020 Booker-winning At Night All Blood Is Black does much the same.) Autobiographically inspired? Without question! But that is only the starting point of the art.

While awaiting an English version of The Storks, take a dive into Broken Glass, or Black Bazaar or any of Mabanckou’s works in English — and definitely score a copy of the new translation, As Long as Trees Take Root in the Earth, beautifully crafted and bound. Vive la Poesie!

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other papers. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, set in Berlin. Recent fiction includes “Evangeline, or Theories of Childhood Development,” in the Iowa Review, and “The Age of Migration,” in Ploughshares. Read Kai’s Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

Tagged: African poetry, Alain Mabanckou, As Long As Trees Take Root in The Earth, Kai Maristed, Nancy Naomi Carlson

Thank you for your incisive comments on BEST AMERICAN POETRY OF 2021 which I have been plowing through and finding the majority of poems disappointing. As you have observed, most lack the lilt of rhythm and are surprisingly overburdened with a diction reminiscent of prose. Before I read your comments I thought I was the sole person in the world thinking this.

Hi Athar and sincere thanks for your comment. Looks like there are at least two of us with similar reactions. There are other voices out there, fortunately. See the recent review here of Martin Edmunds new collection, for example.