Book Review: “Walk With Me” — The Heroism of Fannie Lou Hamer

By Jim Kates

A three-dimensional portrait of one of the most powerful and eloquent leaders of the civil rights movement in Mississippi.

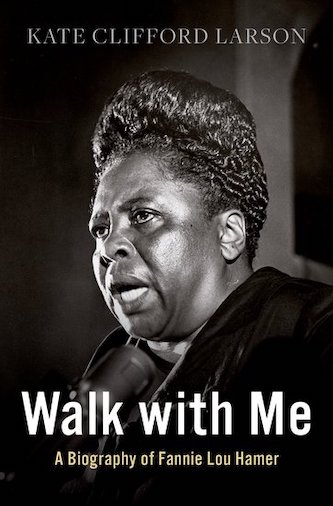

Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer by Kate Clifford Larson. Oxford University Press, 336 pages, $27.95.

When my daughter and I were walking home from her third grade class one January day, she said, “You know, I’m tired of hearing about Rosa Parks.”

When my daughter and I were walking home from her third grade class one January day, she said, “You know, I’m tired of hearing about Rosa Parks.”

She wasn’t putting down Rosa Parks in particular or Black history in general. She has just recognized, in her own third-grade perception, how our presentation of uncomfortable history is dominated by reductive comic-book two-dimensionality and the focus on the heroic leadership of single figures.

“Let me tell you about the bravest person who ever lived,” I replied, and went on to relate the story of Fannie Lou Hamer, an impoverished plantation bookkeeper who was beaten and raped for attempting to register to vote, and who rose up singing to become one of the most powerful and eloquent leaders of the civil rights movement in Mississippi.

The story of Mrs. Hamer — as she will always be to me, who had the privilege of working briefly with her — has been told more than once, and now it appears in Kate Clifford Larson’s concise new biography, Walk With Me. But Larson does far better than I did with my daughter. She frames the subject of her biography not merely as an idol of the civil rights movement. Instead, she uses Mrs. Hamer’s life to tell the larger story of segregation and repression in Mississippi in the twentieth century. And, although this history has been told before, it needs to be told again for each new generation, partly because it sounds so painfully unbelievable from the outside.

Larson begins her account with the legend: the most public moment in Mrs. Hamer’s life, her testimony before the Credentials Committee at the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City in 1964, testimony that shook Lyndon Johnson’s presidency and permanently changed the politics of our country.

Her eight-minute plea ended with a question that haunted many for years afterward: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Scrupulous as she is, as far as I can tell, Larson makes only three minor factual errors and writes only one muddled paragraph. These stand out because the biographer is otherwise so commendably straightforward in her prose and accurate in her details.

Certain of these details might appear irrelevant, but are not. More than once, she focuses on Mrs. Hamer’s clothes and people’s reactions to them. But the way Mrs. Hamer dressed is a significant part of her story — so much so that Roy Wilkins of the NAACP (an incident not recorded in this book) tried to get her to change out of her borrowed “sharecropper” dress into something more “presentable” before she testified in Atlantic City.

Larson is especially good regarding the dynamics of Mrs. Hamer’s work with the young activists in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, such as Freedom Summer leader Charles McLaurin:

McLaurin had initially voiced opposition to the idea of bringing white volunteers to Mississippi, but Hamer convinced him to embrace them. . . . McLaurin later said that he had “found a home”in the movement, and when Fannie Lou Hamer told him to trust her, he did.

Though Larson goes back into Mrs. Hamer’s personal story, interwoven with incidents that many who have not heard them before will find improbably repressive, the biographer is not afraid to question her protagonist’s own representations:

While Hamer later claimed to have been unaware of ‘mass meetings’ or voter registration, her comments don’t reflect her budding activism or her membership in the NAACP. Long before the arrival of SNCC and COFO in Ruleville, Amzie Moore had enlisted Hamer to ‘spread the word’ and encourage her neighbors and church members to become members of the NAACP. . . . She was not as uninformed as she later claimed” and “Hamer’s claim that she would step aside for men to lead was far from the truth. “

Mrs. Hamer’s life of activism and witness, and Larson’s portrait of that three-dimensional life, answer the tumultuous question asked in Atlantic City: Yes, as long as there are decent human beings like Fannie Lou Hamer, America is the land of the free and the home of the brave.

J. Kates is a veteran of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, a contributor to the Mississippi State Museum of Civil Rights, and the editorial co-director of Zephyr Press, publisher of Letters from Mississippi, edited by Elizabeth Martínez.