Book Review: “What Strange Paradise” — Unforgettable

By Jim Kates

Run, do not walk, to pick up your copy of this heartbreaking novel about a little person caught up in a very big world.

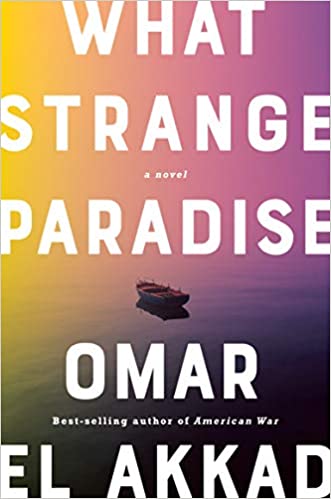

What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad. Knopf, 256 pages, $26.

Omar El Akkad’s What Strange Paradise is a book that challenges reviewers because it is impossible to talk about the book justly without betraying its structure and its end.

Omar El Akkad’s What Strange Paradise is a book that challenges reviewers because it is impossible to talk about the book justly without betraying its structure and its end.

I am reminded in this most of the recently ended production by the Boston’s Actors Shakespeare Project of The Merchant of Venice. Only now can we say out loud that it repeatedly presented itself for four acts as an off-key transgressive comedy only to drop the last act and end with Shylock in Auschwitz. The shock after the schlock was compelling and Brechtian. But who could have written about that while the show was still running, without ruining the effect?

So please put up with the periphrasis below. It will be enough to say that, for the literate, the giveaway to the novel is contained in an epigraph before the story begins.

Run, do not walk, to pick up your copy of What Strange Paradise, a heartbreaking 235-page novel that tells the story of a little person caught up in a very big world, a world we know mostly from pathetic photographs and journalistic accounts, a world already receding from our consciousness in a storm and flood of newer catastrophes.

The world is the Mediterranean between Egypt and Europe, where desperate refugees are still trying to find their way to new lives. As El Akkad presents them to us, these are not nameless victims, but vivid personalities tossed on uncertain seas, pursued by fate: Maher the Palestinian, Mohamed the helpless representative of the traffickers in misery, a gravid woman memorizing her text of English words for arrival: “Hello. I am pregnant. I will have baby on April twenty-eight. I need hospital and doctor to have safe baby. Please help.”

The little person is Amir Utu, an eight-year-old Syrian boy whose family has fled to Egypt, and who has been swept up by an accident of curiosity onto a leaking boat, wearing a useless life-jacket several sizes too big for him, heading unsteadily to the unknown shore of a Greek island.

The storytelling of the novel alternates between a “Before” and an “After,” the fulcrum being the wreckage of the refugees.

A deep cracking sound emerged from somewhere below, the hull giving way. As the Calypso tilted, the flashlight came loose from its hook and was washed overboard. Only the faint backlit clouds and the distant colored lights of shore provided illumination. The passengers screamed and shouted for help, their voices no sooner escaping the boat than they were swallowed by the storm. To anyone standing on the shore the Calypso would have been just another parcel of nighttime, unheard and unseen.

“After,” Amir lives through a comic-book flight from the seemingly ruthless coastal authorities under the direction of a relentless one-legged colonel, with the help of a rebellious local girl, an immigrant from an unnamed Scandinavian home, Vänna.

Vänna enters the farmhouse to find the boy at the far corner, peering into a brown, jug-like container. It’s a jar of maple syrup, a gift from a Canadian couple who stayed at the inn many years earlier. The boy has popped the lid and chipped away at the amber crystals lining the container’s neck. He eats the chippings, the hardened syrup crunching under his teeth, and as she approaches she can smell its burnt sweetness on him.

He sees her. He pauses. He backs away.

“Don’t be afraid,” Vänna says, but she is sure now he doesn’t speak her language. He monitors her the way a small animal might monitor a rustling in the leaves.

The details here — the frightened boy sampling the unfamiliar syrup, the sweetness in the air — and the shifting points of view are persuasive. But the very details are deceptive, different in register from the details of “Before.” I can say no more.

But once you have finished the novel, you can never again be simply “anyone standing on shore,” for whom the Calypso is “just another parcel of nighttime, unseen and unheard.”

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Paper-thin Skin (Zephyr Press), a translation of the Kazakhstani poet Aigerim Tazhi.

I took Jim’s advice and read this stunning book. I couldn’t agree with his assessment more, but want to add that the author implicates his readers, and perhaps himself, in a most startling way, putting a harsh truth into the mouth of someone we have come to resist. Remarkable.