Arts Remembrance: Arnie Reisman — The Party of the First Part

By Nat Segaloff

In a way, Arnie was, to Boston, what George S. Kaufman was to the Algonquin Round Table, except the “vicious circle” lasted only ten years while Arnie enlivened his circle of friends for more than sixty.

My two funniest friends were Arnie Reisman and Dom DeLuise, and I had the honor of bringing them together. Keep reading. Dom died in 2009 and Arnie died on Monday, October 4, for no reason I can think of other than, like losing Dom, to make the world a sadder place.

Arnie and I knew each other for nearly fifty years. The amazing thing is not the length of our friendship, but that it was willed by our friends.

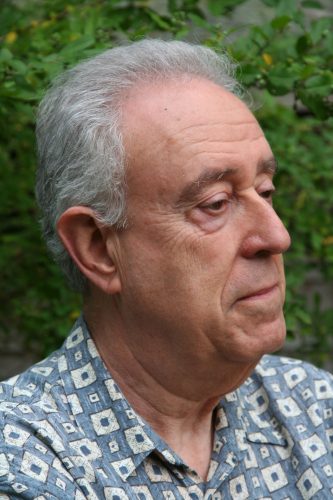

The late Arnie Risman. Photo: Wiki Common.

Let’s go back to Boston, circa 1970 (sometimes I wish I could, and damn Thomas Wolfe). At the time the city had nine newspapers serving the Hub and its spokes: the Globe, the Herald-Traveler, the Record-American, the Sunday Advertiser, the Bay State Banner, the South Middlesex News, the Patriot-Ledger, the Jewish Advocate, and a feisty new “alternative” weekly, Boston After Dark. B.A.D. was called alternative because it covered arts and politics in depth and carried sex ads in a third section which more than paid for the losses incurred by its first two sections covering arts and politics. It also had Arnie Reisman as editor.

B.A.D. was lucky to have Arnie. A graduate of Brandeis and the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, he had freelanced a little before being hired by the Quincy Patriot-Ledger to edit their Limelight arts section. Quincy is a lovely place but not a king-making town, yet Arnie distinguished himself with a verve that matched the changing times. When Roy Rogers’ horse, Trigger, died in 1965, Roy Rogers had him stuffed. Arnie ran the story under the headline ”Trigger Mortis.” They say that’s what brought him to the attention of B.A.D.’s publisher, Stephen Mindich, and in November 1968 Arnie became the paper’s Executive Editor. He lasted until November 1971. (Those who wonder what B.A.D. was like in those days are referred to Joan Micklin Silver’s 1977 film Between the Lines, written by former B.A.D. film critic Fred Barron.)

At the same time, I was making my way in Boston’s journalism circles not as a writer (that would come later) but as a junior press agent for the Paul A. Levi Company which handled several film companies including Paramount and Disney. In those days the movie and theatre publicists would descend on the city’s papers to “service” them with photos, press releases, and pitches for coverage. Gerry Feldman (of the then-fledgling Allied Advertising Agency), Nance Movsesian, Charles Cohen (and his little dog, too), Sack Theatres Publicity Director Jane Badgers, and I would leapfrog from the Globe to the Herald to the Record to the Advertiser on Mondays and Tuesdays plying our wares. We were in competition but weren’t competitors.

I’m going over all of this to show how tight-knit Boston’s movie press was at the time. I’ve also written about it in my memoirs Screen Saver and Screen Saver Too. It was Jane Badgers who finally introduced Arnie and me in 1972 after saying on countless occasions that the two of us ought to meet. We finally did, at Jane’s apartment in Jamaica Plain, at a dinner party that soon became a movable feast.

Jane wrangled six of us into a group. Arnie was married at the time to photographer Nicole Symons. Our friends included film critic Deac Rossell and his wife, graphic artist Mickey Myers. Somehow the six of us decided to have monthly dinner parties on a rotating basis with the only menu restriction being that no one could spend more than two dollars per person, not counting wine. That’s how long ago it was. Therein began a parade of tacos, stews, fondues (!), crepes, casseroles, pastas, and whatever Stop and Shop had on sale that week. The food, of course, ran a distant second to the conversation.

They say that the difference between a comic and a comedian is that a comic says funny things and a comedian says things funny. What leaves skid marks over both of them is wit. Arnie was a wit. He had what I came to call “comedy Tourettes,” meaning that if it was funny, he would say it without regard to how it might make him look. He never scored with anything blue or unkind, nor did he tell jokes per se, or, if he did, he worked them seamlessly into the conversation. When he did, the punch line seemed to surprise him as much as it did everyone who heard it. The exact moment I came to love him I was on the floor of Jane’s apartment, under the table, where I was rolling helplessly after he said, out of nowhere, “Do you know the difference between a tavern and an elephant fart? A tavern is a bar room and an elephant fart is a barROOM!”

They say that the difference between a comic and a comedian is that a comic says funny things and a comedian says things funny. What leaves skid marks over both of them is wit. Arnie was a wit. He had what I came to call “comedy Tourettes,” meaning that if it was funny, he would say it without regard to how it might make him look. He never scored with anything blue or unkind, nor did he tell jokes per se, or, if he did, he worked them seamlessly into the conversation. When he did, the punch line seemed to surprise him as much as it did everyone who heard it. The exact moment I came to love him I was on the floor of Jane’s apartment, under the table, where I was rolling helplessly after he said, out of nowhere, “Do you know the difference between a tavern and an elephant fart? A tavern is a bar room and an elephant fart is a barROOM!”

It wasn’t long after that that he and I began running into each other at parties. At first it seemed like a coincidence, but after a while we began to realize that we were being invited as the entertainment. I can’t speak for myself, but Arnie always managed to lift the level of conversation and I held on for dear life.

Arnie had his able fingers in so many pies that it was inevitable his talent would be recognized away from parties. When Monty Python caught on with public television, he shot a comedy pilot at WGBH-TV with Tony Kahn, Ernie Fosselius, Derek Lamb, and Dick Bartlett called “Mother’s Little Network. It was billed at the time as “the only show on PBS without a British host.” It was filmed, in part, in and around ‘GBH’s Western Avenue building with only one restriction from station management: “Be careful what you shoot. We don’t want the other PBS stations seeing how much money we have.” It never went to series.

It was WCVB-TV that made better use of Arnie’s talents when they brought him aboard Chronicle, station head Bill Bennett’s answer to WBZ-TV’s heavily formatted Evening Magazine. I was on Evening at the time (having switched from publicity to journalism), but Arnie won all the Emmys on Chronicle.

He also wrote plays with Jon Lipsky of Boston Playwrights’ Theater, including a comedy about the assassination of President Garfield called The Second Greatest Crime of the Century, which was never produced, although Arthur Penn considered it for a while.

Through the fog of loss I am also remembering an afternoon in November 1978 when a group of us gathered in my Cambridge apartment to hammer out a script for the “Libby Awards” fundraiser I was producing for the Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts. I don’t recall who did the catering, but the writers were Arnie, Tony Kahn, David Ansen, Fred Barron, and Jon Lipsky. The show itself included David Brudnoy, Robin Young, Marty Sender, Barney Frank, and a comedy troupe called FOYBL Theatre. Years later Arnie would become a Board member of the ACLU of Massachusetts and produce several of their fundraising dinners with their Executive Director Carol Rose.

Somehow this led to a collaboration among Arnie, Tony, and me on the comedy screenplay That’s Tantamount (the title was Arnie’s, natch) a satire of That’s Entertainment about a B-minus movie studio, Tantamount Pictures, that should have gone out of business years ago but never got around to it. We wrote it for a Boston-based distributor who loved it, then stopped paying us and put their money, instead, into the rights to a similar episodic comedy, Tunnel Vision, eventually becoming Atlantic releasing Corporation before burning out. Meanwhile filmmaker Harry Hurwitz coincidentally made a film called That’s Adequate (1989). So much for that gambit.

Over the next couple of decades, even after I moved to Los Angeles, Arnie and I would collaborate on any number of projects. He always found time to do things with others in addition to his own work. I never knew how he made ends meet, but he did. In 1991 he, Daniel M. Kimmel, and I began work on The Waldorf Conference, a play about the 1947 meeting of Hollywood moguls in the wake of the HUAC hearings where they created the Blacklist. It was performed as a staged reading with an all-star cast on NPR in 1993, then sold to Warner Bros. who couldn’t get a TV network interested. We co-wrote a play, Code Blue, about the battle between Otto Preminger and the Production Code over the then-scandalous film, The Moon is Blue, and couldn’t interest a producer. Finally, three years ago, we wrote the screenplay Rembrandt Has Left the Building in which we solved the 1990 Gardner Museum Robbery (hint: my friend did it). It won an award and so far no producer has been smart enough to make it.

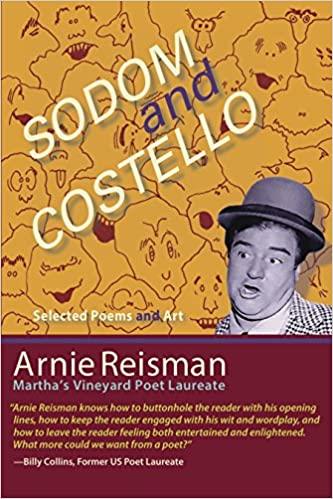

I must sound like a Jonah who doomed every project on which Arnie and I collaborated. Maybe I was, considering the successes had with David Helpern, Jr., James Gutman, and Frank Galvin on Hollywood on Trial (1976), the first documentary about the Blacklist, which was Oscar®-nominated, and with Ann Carol Grossman on The Powder and the Glory (2007), about the feud between Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubenstein that inspired the hit Broadway musical War Paint.What I want to stress is that Arnie was always open to working on something interesting and it never seemed to draw him away from his own efforts, such as two books of poetry (Clara Bow Died for Our Sins and Sodom and Costello), regular columns for the Vineyard Gazette, and becoming one of Boston College’s most popular instructors of journalism.

And then there was Says You!.

The “simple game with words” debuted on NPR in 1996 when it was still called National Public Radio, but it wasn’t an NPR show, it was independently produced by the show’s creator, Richard Sher, who hosted and co-wrote the funny, punny, witty questions, and produced by his wife, Laura Sher. Their son, Ben, was scorekeeper and over 21 years listeners watched (heard?) him grow up. With Arnie leading one team and Barry Nolan leading the other (regular co-panelists were Tony Kahn, Francine Achbar, Carolyn Faye Fox, and Paula Lyons, with others occasionally including me) the ad-libbed “party for smarties” was an oasis in an ever-growing broadcast desert.

Arnie Reisman. Photo: Says You!.

Ah, Paula Lyons. She was Arnie’s match. Boston Irish all the way from a political family and with a no-prisoners respect for the truth, she was Consumer Affairs Reporter, first for WCVB-TV from 1978 to 1989, and then for ABC’s Good Morning America from 1989 to 1994. Paula and Arnie were married in 1982 at the Women’s Education and Industrial Union on Boylston Street, figuring that, given their mixed marriage, either a church or synagogue wedding was out of the question. The Bridget Loves Bernie combo did not go unnoticed; when the priest had the couple say their vows, he announced that the union had been blessed by the Vatican. Not to be upstaged, the rabbi coached Paula in pronouncing her vows in phonetic Hebrew, then smiled at her and said, “Very nice.” Their marriage began with laughter, love, and applause which never diminished so much as one decibel over the next, well, thirty-nine years.

Arnie had a number of trademarks. He could milk someone else’s joke by repeating their punch line in a way that’s hard to describe. If you said, “. . .and so I ride side-saddle,” he would say, in a softer voice, “ride side-saddle.” Don’t ask me how, but it got funnier, and the laugh was yours. He also called Nahanton Street in Wellesley “the Jerry Lewis street” and pronounced it “na-HOYNT-nnnnn.” He had the ability to remain calm in the face of stupidity, although one time he told a lawyer who said he was “sitting on” some paperwork, “Why don’t you let me sit on it? I’ve got an ass.”

Lest anyone think that Arnie was a wisecrack machine, his humor came from a place he didn’t know existed until it erupted. Unlike Shakespeare’s Henry IV, he had no need of bragging, “I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is in other men.” It was self-evident. On one of his and Paula’s “Says You!” sojourns to Los Angeles in the early 2000s, I arranged a lunch with Dom and Carol DeLuise at the DeLuise home in Pacific Palisades. At some point between the pasta and the dolce, Arnie praised Dom’s work in The Thirteen Chairs. Dom gently corrected him, “you mean The Twelve Chairs.” Without a moment’s pause, Arnie shot back, “I saw the director’s cut.” We all broke up and Dom paid Arnie the ultimate compliment: he bowed his head, smiled, clasped his hands, and gave Arnie the laugh. For years after that, Carol would always refer to “that nice couple from the radio who came over to lunch.”

In a way, Arnie was, to Boston, what George S. Kaufman was to the Algonquin Round Table, except the “vicious circle” lasted only ten years while Arnie enlivened his circle of friends for more than sixty. It’s tempting to call someone irreplaceable when you wonder how it happened that he got created in the first place. Not only do I mourn Arnie, I mourn the loss of what he brought to everyone who knew him as well as the loss for those who never did.

Nat Segaloff is a former Boston movie publicist and film critic (not at the same time) who, since then, has written some twenty books, produced a bunch of TV shows, and written a couple of plays. His most recent book is Big Bad John: The John Milius Interviews. He now lives in Los Angeles waiting for his phone calls to be returned.

©2021 Nat Segaloff

I think my most vivid memory of Arnie was one afternoon at his house where he, Nat and I were working on the “Waldorf” script. You know the joke about prison with only one book? It’s a joke book and since everyone had read it the prisoners now got laughs with just the page numbers. That was us. In between hashing out scenes it was jokes and wisecracks where not of us had to say more than a few words for the other two to get the reference. We laughed so much that when Paula came home and heard us she couldn’t believe we got anything accomplished because we sounded like we were having too much fun. I’ll always be grateful to have had that opportunity to work with him.

A great summation of a great life, Nat. Although I did miss any anecdotes of our time together at the Boston College Department of Communications, from whence the Maalox-swilling Chairman used to call Kathleen Cleaver in exile in Algiers! But that’s another story for another time… and with Arnie the stories never ended–and never will, I suspect. RIP

The one BC tale I remember is of a young co-ed (may we still use that term?) who entered our office while Arnie was there alone, closed the door, and asked, “Professor Reisman, is there any way I can earn a better grade in your class?” When Arnie said, “do better work,” she dropped to her knees in front of him and said, “Are you sure there isn’t any way I can earn a better grade?” Arnie looked down at her and said, “I hope you’re on your knees to pray because that’s the only way you’re going to get a better grade.”

And, yes, I remember the colorful Maalox-devouring Dr. Lawton who, in this performance, will be played by John Houseman. He was a piece of work but he managed to cobble together the Speech Communication Department with part-timers like you, Arnie, and me because hiring full-timers meant getting Vatican permission. Thus he created a full department without the Pope finding out.

Nat, a lovely appreciation of what Arnie was — still is — to all of us lucky enough to work by his side, double over at his humor, and share recipes for cardboard when Hollywood passed on our projects and then appropriated then under different titles. Don’t discount your own contribution to our laughter and lovely times; it was great.

I recall with pleasure the four of us — you, Arnie, your faithful dog Ben, and I — lunching at the Orson Welles Restaurant while writing ‘Tantamount.” You two were in such close sync that I learned the most important thing about writing: have a partner who challenges you. The years since then diminished nothing of your talents or my affection for you. I also miss Ben, but by own dog Louie may be reading this, so I’ll be vague. Here boy. Here boy.

Great appreciation. Aways admired his wit and talent. (I was a couple of years ahead of him at Cilumbia and as Patriot Ledger Limelight editor)

Bill Kirtz

Thanks, thanks, thanks, great stories from before I moved to Boston. I knew Arnie only on Facebook, and he quite often commented on my posts. Such a good guy!

Arnie hired me for Boston After Dark Public Occurrences when Steve Mindich was nervous for receptionist. Somehow Arnie found my resume in a pile and hired me as listings editor.($125.00 a week was a lot in 1971!) But I remember his defense of my covering the Cesar Chavez union lettuce boycott, (Stop & Shop might have stopped advertising) after my story ran. And most of all in Martha’s Vineyard, where he lived With Paula and was buried. Stomach-hurting funny he was.

Sincerely,