October Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Books

There is much to admire in the flickers of hard-won existential wisdom Dan O’Brien gives us about a culture that doesn’t want to feel, particularly intimations of mortality.

Dramatist and poet Dan O’Brien’s A Story That Happens: On Playwriting, Childhood & Other Traumas (Dalkey Archive Press, 110 pages) suggests that he may be the most death-obsessed playwright since Eugène Ionesco. At age 42, O’Brien was diagnosed with colon cancer, on the same day in 2016 that his wife, actress and comedian Jessica St. Clair, finished treatment for breast cancer. Both are cancer free now, but the experience has transformed O’Brien, as a person and as an artist. Survival has taught him some bracing lessons, which he shares in the four essays in this brief volume, particularly a refreshingly Jacobean knack for seeing that oblivion can serve as a powerful muse. “One must write while awake to life, to death, in a state of barely controlled terror,” he insists, “but more importantly one’s characters should be terrified too. They should fear for their lives.” This theatrical emphasis on the omnipresence of extinction (a mantra of absurdists from Ionesco and Samuel Beckett to Edward Albee) makes me very curious to see a production of an O’Brien script. To my knowledge, no Boston area theaters have staged one of his plays (such as The Body of an American and The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage), but then our troupes are all about reassuring audiences about their perpetual empowerment — fear strikes out in the box office.

Dramatist and poet Dan O’Brien’s A Story That Happens: On Playwriting, Childhood & Other Traumas (Dalkey Archive Press, 110 pages) suggests that he may be the most death-obsessed playwright since Eugène Ionesco. At age 42, O’Brien was diagnosed with colon cancer, on the same day in 2016 that his wife, actress and comedian Jessica St. Clair, finished treatment for breast cancer. Both are cancer free now, but the experience has transformed O’Brien, as a person and as an artist. Survival has taught him some bracing lessons, which he shares in the four essays in this brief volume, particularly a refreshingly Jacobean knack for seeing that oblivion can serve as a powerful muse. “One must write while awake to life, to death, in a state of barely controlled terror,” he insists, “but more importantly one’s characters should be terrified too. They should fear for their lives.” This theatrical emphasis on the omnipresence of extinction (a mantra of absurdists from Ionesco and Samuel Beckett to Edward Albee) makes me very curious to see a production of an O’Brien script. To my knowledge, no Boston area theaters have staged one of his plays (such as The Body of an American and The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage), but then our troupes are all about reassuring audiences about their perpetual empowerment — fear strikes out in the box office.

O’Brien is aware of that, and he admits that his epiphany makes him an abnormality in the upbeat world of today’s American theater, which is consumed with ‘telling the audience what they want to hear.’ He supplies an eloquent rejoinder for dramatists who don’t want to play the game:

So we listen for what is unspoken in our culture, and it won’t be what our culture wants to hear. But we use our art to make them hear it. They will disagree, because they see things differently; because they don’t know yet how they feel; because they don’t want to feel. The truthful play you write will make you allies and, if you are doing it right, enemies. You will hinder your career by offending those who have risen in their ranks by institutional and commercial rather than artistic acumen.

I wish there was more of that nervy truth-telling in the book. There’s a perceptive insight into why so many contemporary scripts are so flaccid: “It’s as if neoliberal playwrights and their audiences believe that an antagonist is simply a protagonist that we have not yet fully understood.” But this interesting point is dropped. Please, more on the self-interested reasons that “neoliberal” theater neuters significant conflict, tragic and otherwise. Instead, O’Brien recalls what it was like to be raised in a highly dysfunctional family (sliding a little too easily from critical to therapeutic mode) and offers some unremarkable playwriting tips about how to write dialogue and create empathetic characters. Still, there is much to admire in the flickers of hard-won existential wisdom O’Brien gives us about a culture that doesn’t want to feel, particularly intimations of mortality.

— Bill Marx

Film

Hard Luck Love Story is a conscious stab at being one of those moody, ambient, character-driven films which populated Hollywood’s adventurous ’70s.

Sophia Bush and Michael Dorman in Hard Luck Love Song. Andrea Giacomini/Roadside Attractions.

Stop me if you’ve seen this one. The Fugitive Kind (1960), a Tennessee Williams adaptation, had Marlon Brando as a guitar player sprung from jail in New Orleans heading to a new town for a better life. Hard Luck Love Song, a new indie directed by Justin Corsbie, tells of Jesse (New Zealander Michael Dorman) a down-and-out guitar player (and singer) just out of prison in New Orleans for drug-related crimes, arriving in an unnamed city to find himself. Plagiarism or coincidence? Probably the latter, though the Brando movie is the far superior one.

Hard Luck Love Song has a different agenda than imitating Williams. It’s a conscious stab at being one of those moody, ambient, character-driven films which populated Hollywood’s adventurous ’70s. The purpose is made clear in a diner scene where Jesse says to the surly waitress, “Hold on the chicken salad.” She has no idea what he’s muttering about, but, of course, that’s what Jack Nicholson famously said to another clueless waitress in Five Easy Pieces (1970).

Well, emulating ’70s cinema and pulling it off are vastly different. For a while, Hard Luck Love Song is fairly interesting, as we follow Jesse getting a feel for his new environment: he veers automatically to the shady side of town. Director Corsbie mixes in obvious non-actors — a bearded homeless man, denizens of a taco parlor, etc — for a “realist” feel. How does Jesse get the money to get by? He’s a pool scammer, and credibility goes. How do people fall for his obvious scam — pretending to be an inept amateur until the stakes are raised? Didn’t anyone see Paul Newman doing the same in The Hustler?

Whatever, by about 45 minutes in the film begins to die, as we’ve been given no reason to care about what happens to Jesse. And then the movie totally falls apart with the introduction of his ex-girlfriend. What follows is 45 minutes of self-loathing and self-pity from the two loser characters as they fight and make up, and self-denial from director Corsbie, who never catches on that Hard Luck Love Song has become a complete mess.

— Gerald Peary

Classical Music

For intonation, articulation, and tonal security, Nico Muhly’s performance couldn’t be bettered.

Nico Muhly’s violin concerto, Shrink, is the highlight of First Light, a new album (on Pentatone) featuring violinist Pekka Kuusisto and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra (NCO).

Nico Muhly’s violin concerto, Shrink, is the highlight of First Light, a new album (on Pentatone) featuring violinist Pekka Kuusisto and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra (NCO).

Written for Kuusisto, Shrink’s three movements obsess, on the one hand, over intervals: ninths in the first, sixths in the second, and …others in the third.

However, this concept takes a back seat to Muhly’s engrossing musicality in the concerto. His writing for the violin is stunning: Muhly clearly knows what the instrument can do. Yet he always employs violinistic tricks — left-hand pizzicato, bariolage, harmonics of various stripes, etc. — to expressive ends.

Much of his writing in the outer movements of Shrink is motoric and nervous. The shapely first is like an aural hall-of-mirrors, with deft echoes, continuations, and completions of lines between soloist and orchestra.

Affecting, too, is the central movement, its opening shimmering like a desert mirage before unfolding into a series of heterophonic lines.

Kuusisto plays it all magnificently. For intonation, articulation, and tonal security, his performance couldn’t be bettered. Ditto for the tight, colorful “accompaniment” of the NCO.

Shrink is balanced out with music by Philip Glass.

Kuusisto’s string-orchestra adaptation of Glass’s String Quartet no. 3 (Mishima) is solid; hearing a bigger ensemble play this music — especially the gorgeous last movement — is, indeed, alluring.

In this performance, the first three movements are oddly lethargic, lacking dynamic contrasts, and edge. Happily, the last three are warm, propulsive, and cathartic — but where that spirit was in Mishima’s first half is a mystery.

There’s no disconnect, though, in The Orchard, a gentle, slightly sour waltz that Kuusisto and Muhly play between the earlier selections. Taped on opposite sides of the Atlantic — Kuusisto was in Helsinki, Muhly in New York — you’d never know: the engineering (and the duo’s feel for the music) is flawless.

The music’s enormous reservoirs of joy, perseverance, struggle, and triumph come across palpably

Just when one thought (hoped?) that the catalogue of Beethoven piano concerto recordings had met its limit, along comes Krystian Zimerman with a new traversal (on Deutsche Grammophon) of The Five. Serves me right for ever entertaining such a heresy.

Just when one thought (hoped?) that the catalogue of Beethoven piano concerto recordings had met its limit, along comes Krystian Zimerman with a new traversal (on Deutsche Grammophon) of The Five. Serves me right for ever entertaining such a heresy.

This is Zimerman’s second recording of the set. For his first (30 years ago), he teamed up with the Vienna Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein; Bernstein died before finishing the cycle, so Zimerman led the first two concerti from the keyboard.

Here, he’s joined by Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO). It’s an inspired partnership.

Their account of the Concerto no. 1 is spirited and invigorating, full of tight exchanges between soloist and orchestra. There’s no want of character in the Second: the outer movements offer plenty of play, while the central one wants nothing for soulful focus.

The Third Concerto really dances, thanks, in part, to the wonderfully articulated delivery Zimerman and the LSO conjure up. In the Fourth, their playing is subtle and characterful — nowhere more so than in the bold, gripping account of the slow movement. And Zimerman’s Emperor Concerto is as mighty and idiomatic as one might desire: golden-toned in the first movement, serene in the second, swaggering lustily in the finale.

Where does it leave us? With some pretty fine Beethoven, by any measure.

Granted, I don’t prefer this Beethoven cycle to Zimerman’s first: the sheer electricity of the three concerti Bernstein was there for is unbeatable (this really comes across on the videos of those concerts). Rattle and the LSO don’t want for technique or brio, but some textural issues periodically arise thanks to the orchestra being socially distanced.

That said, the music’s enormous reservoirs of joy, perseverance, struggle, and triumph come across palpably. The performances justify themselves — which is precisely what this repertoire demands.

Jean-Jacques Kantorow’s isn’t the most pristine of Saint-Saëns symphony cycles. But it surely counts among the more characterful.

The best of Camille Saint-Saëns’s copious output remains as fresh and inventive as anything by his contemporaries, particularly Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, and Stravinsky.

The best of Camille Saint-Saëns’s copious output remains as fresh and inventive as anything by his contemporaries, particularly Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, and Stravinsky.

That’s certainly true of his Symphony no. 3. Famed for its inclusion of the organ into the orchestral fabric, the piece also includes a piano (played by two pianists — just like in the Carnival of the Animals, which dates from the same year, 1886).

Novel as the scoring is, what really makes the Symphony is Saint-Saëns’s flawless gift for melody and drama: a thrilling, toccata-like first movement followed by one of the most serene slow movements in the repertoire. The third movement is a furious dance that’s capped by one of the great, blazing finales of the canon. What’s not to love?

In Jean-Jacques Kantorow’s new recording (BIS) of the Organ Symphony with the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège (OPRL) — the second of a two-volume complete Saint-Saëns symphony set — there’s a strong feel for the music’s dancing energy, especially over the last two movements. Throughout, the organ is embedded in the orchestral texture, which smartly fits the larger character of the writing.

The only serious interpretive issue arises in the first movement, whose brisk passagework sounds manic.

A similar problem appears in Kantorow’s aggressive account of the first movement of Saint-Saëns’s early Urbs Roma Symphony, which completes the disc.

This periodic heavy-handedness makes for an odd contrast with the rest of the reading, in which the lyrical writing sings. Indeed, the OPRL woodwinds’ playing in the second movement of Urbs is precise, while the third’s strict marching figures contrast nicely with its broader, songful episodes. In the finale, Kantorow’s forces deliver a graceful, elegant account of the concluding variations.

Perhaps, then, Kantorow’s isn’t the most pristine of Saint-Saëns symphony cycles. But it surely counts among the more characterful.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

La Reine de Saba contains one of the most enchanting ballet sequences I’ve heard in any opera, beautifully realized by Opera Odyssey’s orchestra under Gil Rose

I have previously welcomed three recordings from Boston’s Odyssey Opera: Gunther Schuller’s The Fisherman and His Wife, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s The Importance of Being Earnest, and Norman Dello Joio’s The Trial at Rouen. Here is yet another of their important rediscoveries released on its label BMOP/sound: the first complete recording of Charles Gounod’s La Reine de Saba (The Queen of Sheba), a work that received its first performance at the Paris Opéra in 1862. Large chunks of music are apparently recorded here for the first time. And the sequence of events is sometimes surprising, for anyone who might know the (rare) previous recordings of the work. The big tenor aria, well known from some aria discs, now opens the opera instead of being placed in the middle of the second act.

I have previously welcomed three recordings from Boston’s Odyssey Opera: Gunther Schuller’s The Fisherman and His Wife, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s The Importance of Being Earnest, and Norman Dello Joio’s The Trial at Rouen. Here is yet another of their important rediscoveries released on its label BMOP/sound: the first complete recording of Charles Gounod’s La Reine de Saba (The Queen of Sheba), a work that received its first performance at the Paris Opéra in 1862. Large chunks of music are apparently recorded here for the first time. And the sequence of events is sometimes surprising, for anyone who might know the (rare) previous recordings of the work. The big tenor aria, well known from some aria discs, now opens the opera instead of being placed in the middle of the second act.

Reine is a typical instance of French Grand Opera, a genre that dominated opera houses in many lands for decades and that, similar to the historical-epic films of Hollywood’s Golden Age studios, focused on notable strife-riven eras and events and involved much expensive scenery and costumes, but also tried to maintain total accessibility in manner and style. The resulting works largely disappeared from the repertory in the early 20th century, even the best known of them, such as Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots and Halévy’s La Juive. But a renewed appreciation for the diversity of Romantic music and theater in the past few decades has brought many such works back, including the full five-act version of Verdi’s Don Carlos and Berlioz’s magnificent Les Troyens.

Of La Reine de Saba — which tells of a love triangle involving the Queen of Sheba, King Solomon, and the chief architect of Solomon’s kingdom — only that tenor aria and an aria for Queen Balkis (“Plus grand, dans son obscurité”) are at all familiar. But Gounod’s music is full of attractive melodies, grateful and well-characterized vocal lines, colorful and varied orchestration, juicy choruses, and some welcome sudden shifts of dramatic tone. Reine also contains one of the most enchanting ballet sequences I’ve heard in any opera, beautifully realized by Opera Odyssey’s orchestra under Gil Rose. The singers are all intelligent and responsive, though several have a slow, wide vibrato that tires the ear. (Order the CD and listen to selections here.)

The biggest drawback is the printed libretto, whose translation is riddled with elementary errors (e.g., translating “son” as “his” or “its” when it should be “her”). “De mon” gets mistranscribed as démon and therefore translated as “demon,” momentarily introducing a devil into the story.

— Ralph P. Locke

Jazz

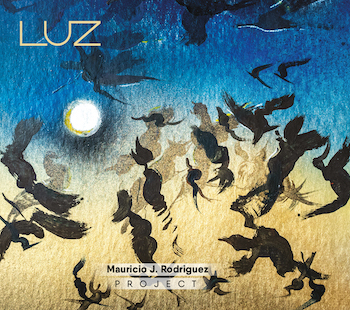

Luz is imaginative Latin jazz, and Mauricio J. Rodriguez is a composer deserving of wider recognition.

Mauricio J. Rodriguez is a virtuoso Latin jazz bassist, currently the Composer-in-Residence for the Miami Symphony Orchestra. The music on Luz (self-released) is lush, detailed, and airy; the compositions are suggestive and inviting; and the players are disciplined and inspired.

Mauricio J. Rodriguez is a virtuoso Latin jazz bassist, currently the Composer-in-Residence for the Miami Symphony Orchestra. The music on Luz (self-released) is lush, detailed, and airy; the compositions are suggestive and inviting; and the players are disciplined and inspired.

Luz emphasizes textures, not flashy solos or filling the dance floor. Latin rhythms often take a submerged role from deep within the interplay of the musicians. “Danzón No. 1. Opus 1 con Cha” is the exception. It is the most conventional Latin track, appropriate for the Cuban national dance, with driving Cuban percussion and traditional Cuban solo styles from José Sardiñas on clarinet and Gabriel Cadenas on piano. Even so, “Danzón” is uncrowded, melodic, and romantic.

“Es el Amor” showcases the emotive (but never melodramatic) voice of Adrianna Foster, whose dreamy optimism counterpoints the worldly heartbreak of cellist José Pradas. “Tuesday” is a completely different up-tempo jazz composition, featuring Zachary Bornheimer’s elegant oboe-like sound on soprano. On “Wednesday,” Bornheimer has a rougher sound on tenor in a duet with pianist Cadenas. It would be interesting to see the score for “Wednesday” — there’s a classical piano introduction, some doubling of the bass with the pianist’s left hand, and some intriguing overtones in the dialogue between players over a difficult time signature.

Rodriguez is a maximalist bass player. He won’t play one note where 10 will do. On “My Funny Valentine,” Rodriguez overloads with chords and arpeggios, like a guitarist. The abrupt transition into a classical baroque duet between two overdubbed electric basses doesn’t help, and it has little to do with the song (or even, to my ear, the changes).

Luz is imaginative Latin jazz, and Rodriguez is a composer deserving of wider recognition. Fans of the Pat Metheny Group and Chick Corea’s larger ensembles will enjoy giving it a careful listen.

Yes, it swings. Hard. Like hammock-in-a-hurricane hard, at every tempo, just as the Count would have it.

I confess I rolled my eyes when I read about this one — the Count Basie ghost band was going to recreate what I believe is one of the greatest jazz albums ever: Count Basie Live at Birdland, recorded in 1960. They are even echoing the original cover art. There’s nowhere to go but down: here’s a ghost band playing at a ghost night club (the original Birdland closed in 1965; the present club opened in 1996 at a completely different location and trades off the famous name). I expected about as much from this as I would from a Jimi Hendrix cover band playing a festival in Woodstock, Illinois.

I confess I rolled my eyes when I read about this one — the Count Basie ghost band was going to recreate what I believe is one of the greatest jazz albums ever: Count Basie Live at Birdland, recorded in 1960. They are even echoing the original cover art. There’s nowhere to go but down: here’s a ghost band playing at a ghost night club (the original Birdland closed in 1965; the present club opened in 1996 at a completely different location and trades off the famous name). I expected about as much from this as I would from a Jimi Hendrix cover band playing a festival in Woodstock, Illinois.

I am happy to report that I was completely, utterly, and spectacularly wrong. This double album (on Candid) is a gem. I listened to all 33 songs straight through and never got weary of it — the arrangements are either from Basie’s original songbook or in that spirit, the ensembles are tight where they should be and loose where they should be, and even the recording captures the ambiance and feel of the original album. And, yes, it swings. Hard. Like hammock-in-a-hurricane hard, at every tempo, just as the Count would have it.

The style of the band is much like Basie left it when he died in 1984. It’s pleasantly retro where it needs to be with the hits dating back to the ’30s, but most charts are in the mode of the Basie bands that recorded those loose-limbed and joyful sessions on Pablo. Every solo and vocal turn is terrific, and there are many, with honors going to trombonist Clarence Bank who is apparently the reincarnation of Al Grey.

There’s nothing quite like hearing a hard-swinging big band full of excellent musicians having the time of their lives on a dream gig.

— Allen Michie

Rock

As implied by its name, Vapors of Morphine rose from the ashes of Morphine, the Cambridge low-rock trio steered by singer and two-string slide bass inventor Mark Sandman, who died onstage in Italy in 1999. Morphine baritone-sax beacon Dana Colley and original drummer Jerome Deupree carried that legacy into a new trio with New Orleans blues guitarist/singer Jeremy Lyons picking up Sandman’s signature low-end axe as part of an arsenal that includes electric bouzouki.

As implied by its name, Vapors of Morphine rose from the ashes of Morphine, the Cambridge low-rock trio steered by singer and two-string slide bass inventor Mark Sandman, who died onstage in Italy in 1999. Morphine baritone-sax beacon Dana Colley and original drummer Jerome Deupree carried that legacy into a new trio with New Orleans blues guitarist/singer Jeremy Lyons picking up Sandman’s signature low-end axe as part of an arsenal that includes electric bouzouki.

On its long-gestated third album, Fear & Fantasy (Schnitzel Records), Vapors of Morphine continues to tap a moody, atmospheric sound in line with its root inspiration while taking disparate sonic detours that reflect the broad musical tastes of its members.

Both the familiar and the novel emerge in lead track “Blue Dream.” A banjo-sprinkled field recording of foot-crunched leaves and birdcalls (a blue jay, natch) sets up the song’s hazy and, yes, dreamy mix of vocals and sax effects around a riddim and melody that suggests a merger of dub reggae and sea shanty. The dark drifting continues in “Golden Hour,” where Colley sounds like he’s singing down a tunnel, in tune with the low buzz of his harmonized saxes.

Over an elastic twang, “Irene” extends an opening theme, with Lyons singing “I dream, ’cause dreams will give you wings” — a seeming wink to Morphine’s “A Head with Wings.” And in similar headspace, a phased drum break from Deupree drops into Lyons’s “No Sleep,” which sounds as woozy as a sleepwalk, about a wine-fueled evening where “I just hope that I don’t come on too strong.”

But the album’s second half, where new Vapors drummer Tom Arey (Peter Wolf, Ghosts of Jupiter) takes over from Deupree, goes off into other stylistic territory. It starts with the Middle Eastern–tinged African desert blues of Ali Farka Touré’s “Lasidan,” a Malian influence that returns in the hypnotic swells of Boubacar Traoré’s “Baba Drame” over Arey’s dancing drum hits. And the overtly catchy “Drop Out Mambo” rides Lyons’s playful, lively vocal and spicy palette of stringed outbursts, a reminder of when Los Lobos would jump into an extroverted mode.

The band eschews Morphine covers for this outing, yet one can still almost hear Sandman’s voice in “Doreen.” Maybe that makes sense since the tune hails from his older band Treat Her Right, replete with a frisky “What’s that name?” setup for its call-and-response chorus.

Fear & Fantasy winds out with sound-effected filler “Phatasos & Phobetor” and the dobro-styled, jug-band ditty “Frankie & Johnny,” a combo that contrasts the trippy and the accessible — a flexible form that Morphine managed so well, and Vapors have adopted in their own way, sometimes separating the strands.

— Paul Robicheau

Jason Isbell is the kind of songwriter who compels you to lean in to hear every lyric and rejoice in every hot lick. He brought all these elements together at a recent show in Boston.

Jason Isbell. Photo: Alysse Gafkjen

More than a decade ago, Jason Isbell, formerly with the Drive-By Truckers, went solo and has released a number of strong albums under his name and with an outfit he calls the 400 Unit (which typically includes his wife, fiddler Amanda Shires). His blend of earnest country-folk and spicy Southern rock has broad appeal, and whether he’s delivering a tender ballad or a torrid rocker, Isbell hits the mark time and time again. He’s the kind of songwriter who compels you lean in to hear every lyric and rejoice in every hot lick. He brought all these talents together at a recent show at the Boch Center Wang Theatre on September 18.

Prior to the gig, Isbell made headlines with his insistence that every venue he plays must enforce a strict vaccination and mask policy, and he took time during the concert to thank fans for adhering to the mandate. Beyond the medicinal politics of the day, Isbell was on hand to please, and please he did. The sound was good, his band was strong, and Isbell himself was in fine voice and ripped off some emotional guitar leads. That his fans were with him was evident from the strong applause he received in the middle of the song “Cover Me Up” when he sang that “I sobered up and I swore off that stuff forever.”

His 22-song set ranged through his various albums and included a song by REM (“Driver 8”) that appears on a forthcoming album of covers called Georgia Blue (release date October 15). Though Isbell has been playing various Rolling Stones songs this tour in memory of Charlie Watts, the Boston audience was treated instead to a searing cover of the early Fleetwood Mac classic “Oh Well” as an encore. No complaints here.

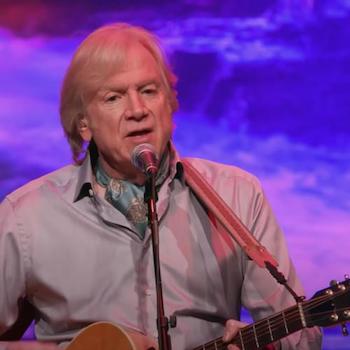

From beginning to end of Justin Hayward’s 14-song set, you could close your eyes and believe it was 1971 rather than 2021.

Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues. Photo: courtesy of the artist

As rock legends from the ’60s and ’70s move into their septuagenarian and octogenarian years, the signs of age are noticeable — most notably, the voices have deteriorated. That’s to be expected. What was not expected was hearing Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues, who will soon turn 75, delivering his trademark honey vocals with nary a strain at City Winery in Boston on September 28. From beginning to end of his 14-song set, you could close your eyes and believe it was 1971 rather than 2021.

Fronting a sparse but exquisite backing band — including Michael Hedges disciple Mike Dawes on lead acoustic and electric guitars (he also opened the show with a startling 20-minute acoustic solo set demonstrating his percussive approach to the instrument); Julie Ragins, who has performed with Hayward on solo tours as well as with the Moody Blues, on keyboards and vocals; and Karmen Gould, a classically trained flutist and vocalist who looks every bit the California girl she is — Hayward performed Moody Blues classics from the ’60s to the ’80s, as well as two songs from a 2013 solo album.

Highlights included “Tuesday Afternoon” and “Nights in White Satin” from the groundbreaking 1967 album Days of Future Passed, “The Actor” from In Search of the Lost Chord, “Question” from A Question of Balance, and “The Story in Your Eyes” from Every Good Boy Deserves Favour. Oddly, two Moody Blues albums that this writer feels contain some of his best work, To Our Children’s Children’s Children and Seventh Sojourn, went untouched. He did, however, play “Forever Autumn” from a 1978 album based on The War of the Worlds and masterminded by composer Jeff Wayne, which inspired the first standing ovation of the night. But not the last.

— Jason M. Rubin

Visual Art

Kristy Edmunds, the new director of Mass MoCA. Photo: Mass MoCA

I am confused. For decades, I have thought about Mass MoCA as a cutting-edge visual arts museum with the largest space available in the world for contemporary visual arts. These forms ranged from the ethereal to the permanent, from performance to solely physical project based. Joe Thompson, an original founder of Mass MoCA, stepped down as the director after 32 years last winter. He has been replaced by Kristy Edmunds who has a resume of presenting dance, theater, and music as well as some cross-disciplinary and experimental projects. These are said to have included visual and digital art. Were these backdrops to performances?

Edmunds previously served as the artistic director of the Melbourne International Arts Festival and the head of the School of Performing Arts and deputy dean at the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne. She was also the founding executive and artistic director of the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art and the Time-Based Art Festival (TBA) in Portland, OR. And she has served as the inaugural consulting artistic director for the Park Avenue Armory in New York.

In other words, Edmunds is an entertainment impresario. Unlike Thompson, visual arts is not a background of hers but an add-on. Clearly, she is an effective fundraiser for performing arts festivals. But how does that skill mesh with leading what is, primarily, a visual arts museum/institution? And one that was financially downsized by 20% during the 2020-21 pandemic.

To underscore her “fit,” the Mass MoCA website now states that 50% of all the museum’s programming is performing arts. Really? Bang on A Can, FreshGrass, and other concerts are appealing events, but they are secondary to the visual art on display. Was performing arts an initial element in the mission of MassMoCA? Over time, they were added to increase audience attendance and diversify demographics. Over the decades, the number of performances have increased. But MassMoCA has always been — at its heart — a visual arts destination. Edmunds was certainly a “woke” choice for new director. Time will tell if it was a good one.

— Mark Favermann

Tagged: A Story That Happens, Allen Michie, BMOP/sound, Bill-Marx, Bis, Dalkey Archive Press, Dan O'Brien, Deutsche Grammophon, Fear & Fantasy, Gerald Peary, Gil-Rose, Hard Luck Love Song, Jason Isbell, Jason M. Rubin, Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Jonathan Blumhofer, Justin Corsbie, Justin Hayward, Kristy Edmunds, Krystian Zimerman, La Reine de Saba, Luz, MASS MoCA, Mark Favermann, Mauricio J. Rodriguez, Nico Muhly, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Odyssey Opera, Paul Robicheau, Pentatone

Asking Mark Favermann to give Kristy Edmunds a chance at Mass MoCA. I had the chance to hear her speak to the dancers after the CAP-UCLA performance of Merce Cunningham: Night of 100 Solos. She clearly understands how to present and talk about contemporary art. (Funny how Merce’s work remains contemporary.) The brilliant visuals by Jennifer Steinkamp went way beyond “backdrop”. I think Ms. Edmunds could be an “entertainment impresario” of the best kind, and a lot more.