Book Review: “The Commune” — Don’t Iron While the Strike Is Hot

By Nicole Veneto

As an example of historical revisionism, The Commune proffers a valuable representation of the cultural, political, and class dynamics that animated the Women’s Liberation Movement.

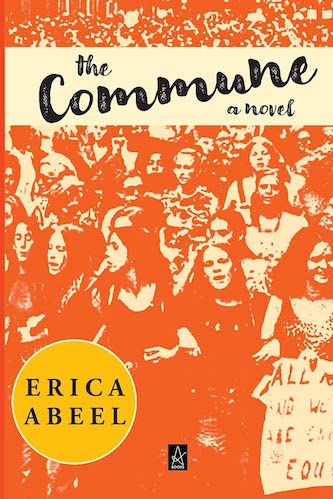

The Commune by Erica Abeel. Adelaide Books, 329 pages, $27.70.

It is a bit of a dirty secret, but social justice movements, as altruistic and well intentioned as they may be, can (and frequently do) devolve into a clout game for those in the upper echelons of leadership and media visibility. I’m a militant feminist, yet I’ll be the first to admit that the movement itself has been plagued by its fair share of bad faith grifters, egotistical gatekeepers, and — worst of all — co-opting by wealthy/upper-class elites for whom a #GirlBoss CEO is the pinnacle of gender equity. The worst of these impulses have been ramped up by the social media panopticon: every interaction is a marketing opportunity for the accumulation of social capital. Opportunism, however, is by no means a recent phenomenon confined to the internet age. Behind every past outburst of communal solidarity and collective activism lie tentative bonds between different political and social factions ready to be severed. Feminism, in particular, proffers a fraught history of internal schisms along racial, sexual, and classed lines. The result has been less a unified movement than a seasonal story-arc for Succession.

It is a bit of a dirty secret, but social justice movements, as altruistic and well intentioned as they may be, can (and frequently do) devolve into a clout game for those in the upper echelons of leadership and media visibility. I’m a militant feminist, yet I’ll be the first to admit that the movement itself has been plagued by its fair share of bad faith grifters, egotistical gatekeepers, and — worst of all — co-opting by wealthy/upper-class elites for whom a #GirlBoss CEO is the pinnacle of gender equity. The worst of these impulses have been ramped up by the social media panopticon: every interaction is a marketing opportunity for the accumulation of social capital. Opportunism, however, is by no means a recent phenomenon confined to the internet age. Behind every past outburst of communal solidarity and collective activism lie tentative bonds between different political and social factions ready to be severed. Feminism, in particular, proffers a fraught history of internal schisms along racial, sexual, and classed lines. The result has been less a unified movement than a seasonal story-arc for Succession.

Accordingly, nearly 51 years have passed since the Women’s Strike for Equality brought second-wave feminism to the international spotlight, but the frenzied clash of egos, gender politics, and cultural agendas in Erica Abeel’s satirical novel The Commune sheds considerable light on today’s dysfunctions. There is little here of the idealized past in which Women’s Lib flourished from a neatly uniform sense of sisterhood.

Combining Jane Austen’s romance plots with a Gatsby-inspired caricature of New York’s wealthy donor class, The Commune fictionalizes the months of organizing that led up to the monumental Women’s Strike in the summer of 1970, transporting the action to the titular commune located in Olde Islesfordd, a fictional Long Island town where old money and the nouveaux riches spend their summers. Against this bourgeois backdrop, Abeel forges a critique from inside the feminist matrix, throwing a spotlight on the contradictions and interpersonal discord gestating within the movement, primarily those of class, sexual identity, and political gatekeeping. There is nothing especially groundbreaking or scathingly critical in this farce but, as an example of historical revisionism, it’s a valuable representation of the cultural, political, and class dynamics that animated the Women’s Liberation Movement.

One of the most persistent criticisms lobbed against liberal feminism is that it’s historically been led by (and benefited) middle and upper-class women, carefully eluding issues of class inequality with lip service about “female empowerment” that lets capitalism off the hook for digging its heels into the necks of men and women alike. Abeel (who writes on film for the Arts Fuse) traces the collusion between liberal feminism and the mechanisms of corporate capitalism back to the exclusive banquets and grand dinner parties where rich “fat cats” write “fat checks” in exchange for “nice tax write-off[s]” and a coveted spot on the right side of history.

Much of The Commune follows freelance writer Leora Voss, a newly separated mother of two with dreams of writing for Gotham, and her attempts to breach the commune’s inner circle of influence while rekindling a romance with the seemingly Gatsby-esque Kaz Gabowski. As Leora bluntly points out, freelance writing doesn’t provide a comfortable living wage or supply the luxuries of health benefits, especially when you have young children to raise. Though she’s living the life of total “autonomy and going at it alone” espoused by the rhetoric of Women’s Lib, Leora is desperate for some sort of stability: “[S]he’d already done autonomy and would now happily become a prostitute…. All this autonomy had got her where? In a fanged struggle for survival.” Hoping to find a much-needed lift out of poverty and envisioning the commune as a “gateway to a better class of potential mates” than her ex (as well as a source of creative inspiration), she travels out to the Islefordd commune only to find it’s more of a pretentious “kindergarten” class than a group of sexual revolutionaries ready to offer any sort of broad solidarity to her.

Abeel makes it perfectly clear that the communards aren’t all that different from Islesfordd’s wealthy bourgeoisie, and the level of snobbish gatekeeping Leora experiences from the politically enlightened (most of whom treat her as if she isn’t even there) speaks more to the degradations doled out by class prejudice rather than gender. She shares more with the “invisibles, the bit players and servers” — “the vanished baymen, indigenous people, the Wilfredo houseboys and Black maids who used the Service Entrance” — than with the ambition-blinded women of the commune caught up in their own elevated sense of self-importance.

Author Erica Abeel

But The Commune is also the story of Edwina Scahill, a photographer of Islefordd’s “jet-setters and socialites” whose love affair with radical lesbian feminist JoBeth Mankiller scandalizes her fellow communards; it’s about Nadine Kusnetz, the commune’s second-in-command, and her struggles for love after hitting menopause and coming to the “controversial” opinion that feminism needs to be “more empathetic towards men and their well-earned woes” if it’s to accumulate meaningful political power; and of the egotistic motivations fueling Gilda Gladstone, the self-appointed mother of the movement who, like her historical counterpart Betty Friedan, launches into paranoid homophobic tirades about how the “lavender menace” is a CIA operation and spits jealous antipathies against the rising-star of the movement, Monica Fairley. The latter is a marginal character standing in for second-wave icon — and actual CIA spook, in case you didn’t know — Gloria Steinem. In one way or another, all these women shed light on a group that’s overlooked by both mainstream and radical separatist strains of feminism: queer women, women over 50, blue-collar women, and even the younger generations who can clearly see how lethally conflicts of interest undercut the movement (Gilda’s own daughter, Becca, is arguably her most savage critic: “If you weren’t Ma Feminism, Family Court would have put me in foster care for gross neglect.”)

Unfortunately, mainstream history mistakenly attributes the successes of the feminist movement to a small yet socially and economically privileged group of liberal feminists and their associated organizations. From this perspective, Women’s Lib was spearheaded by Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and the National Organization for Women (NOW). The truth is that the groundwork was laid by women in the New Left, antiwar, and Civil Rights movements. This is not to say that Friedan, Steinem, or NOW didn’t make important contributions to feminist history — as class-blind and homophobic as Freidan was, I still have a copy of The Feminine Mystique on my bookshelf. (My second-wave mother gifted it to me like a passing of the generational torch.) But their willingness to ally their gender politics with the forces of corporate capitalism and the military industrial complex calls for skepticism, to say the least. When these kinds of alliances are excused as efforts to “co-opt” — the commune’s “favorite word” — oppressive institutions and change them for the better (take the CIA’s “woke” recruitment campaign), our first instinct as feminists ought to be to determine who or what such efforts are actually helping. Chances are that it isn’t poor women, single mothers just scraping by, women in the global south, underpaid caretakers and domestics, or any of the millions of young women saddled with crippling amounts of student loan debt.

Despite its doses of ridicule, the narrative ends with a stirring look at the monumental Women’s Strike on August 26, 1970, which gives readers the comfort of knowing that real, meaningful actions, via demonstrations of mass solidarity among women, are possible. Granted, it takes a lot of infighting and drama behind the scenes to get there. Still, there’s a genuine sense of triumph at the book’s conclusion, when the Strike’s turnout floods Fifth Avenue with women (and men) from all walks of life. We know the course history took after that, but the march’s turnout — without the aid of social media hashtags or the lure of pink pussy hats — is still mind-blowing. With the Strike’s 21st anniversary just around the corner, The Commune provides an entertaining way to revisit a crucial moment in feminist history.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader.