Author Interview: Aaron S. Lecklider on the Forgotten History of Homosexuality and the Left in American Culture

By Blake Maddux

The reader comes away from Love’s Next Meeting with an awareness of the rich history of homosexual culture that existed long before the Stonewall riots in the summer of ’69.

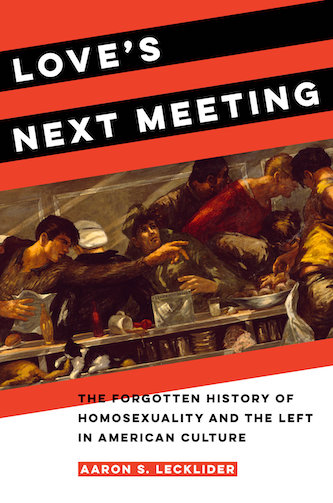

Love’s Next Meeting: The Forgotten History of Homosexuality and the Left in American Culture by Aaron S. Lecklider. University of California Press, 376 pages, $29.95.

Aaron S. Lecklider is an associate professor in the department from which he earned his master’s degree, namely, American Studies at UMass Boston.

A New Hampshire native who earned a PhD from Boston University, Lecklider specializes in 20th-century American cultural history with emphases on sexuality, gender, race, and class.

All of these elements coalesce splendidly in his new book, Love’s Next Meeting. The volume’s overarching categories — deviant politics and sexual dissidence — are divvied up in chapters that scrupulously explore their interface with, for example, labor, gender, proletarian literature, and antifascism between 1920 and 1960.

The reader comes away from Love’s Next Meeting with an awareness of the rich history of homosexual culture that existed long before the Stonewall riots in the summer of ‘69.

Professor Lecklider spoke to The Arts Fuse by phone on the day after the book’s publication date.

The Arts Fuse: Which audiences within and outside of academia will benefit from reading Love’s Next Meeting?

Aaron Lecklider: Within the academy, I wrote the book for scholars in the history of sexuality and 20th-century American history, scholars of American literature, and people who study radical social movements in the US. Outside of scholarly audiences, my goal was to write a book that would be on some level inspiring to queer people and activists who are doing work today, but also would offer some cautionary tales as well about things that should be avoided. But it’s not a how-to manual. It’s drawn from deep, deep archival research. I tried to write something that was going to be instructive in some way but not prescriptive.

AF: There is a paragraph more than three-quarters of the way into the book in which you discuss the possible meanings of “love’s next meeting.” What do you think it means and why did it make for the best title?

Aaron Lecklider. Photo: Michael Sullivan.

Lecklider: I really wanted this title for several reasons. I wanted a title that pointed to futurity. Meetings in this case are of two different kinds. One is a kind of sexual liaison, another is the kind that all activists have to sit through, and endure, and sometimes take inspiration from in order to get their work done. Part of what I think sustains both sexuality and radicalism is that sense of a future. That sense that there will be another meeting, so that even if things don’t go well one time, there’s always something to look to in the future. So I liked the phrase, which comes from a poem by John Malcolm Brinnin, because it pointed not to the last meeting but the next one, and that represents to me hope.

AF: Is it possible to briefly sum up the fraught relationship between sexual dissidents and the Communist Party, which you describe as “the political hub of the Left especially after the onset of the Great Depression”?

Lecklider: It would be a tremendous mistake to narrate a history that does not acknowledge very explicitly that the Left was not a place that was universally hospitable to queer people. The relationship between the organizing structure of the Communist Party and homosexuality looks pretty bad from the top down. But I was also interested in looking at the bottom up. The people on the ground didn’t necessarily find their entire radical politics defined by what the disciplinary commission of the Communist Party told them it should look like.

People who involved themselves with the Communist Party were already putting themselves outside the norms of general society just for being there, so they were well-equipped to be able to ignore directives. I think that that primed some of these folks who were looking at homosexuality differently to be able to say, for example, I’ll accept the radical labor piece but I’m not going to accept the antipathy toward homosexuality.

AF: Why would they work with the party if they were (rightfully) unwilling to accept its disapproval of something so fundamental to who they were as human beings?

Lecklider: The Communist Party was not exceptional in the ’30s in being a homophobic organization. The entire country was homophobic. So I think that the impediment of homophobia was not the baseline for these folks to organize their sense of belonging within communities and organizations. It was not unusual or unexpected to them. It was just what you get. The politics of visibility around sexuality is just not the primary lens into social movement building that I think is legible to earlier activists. Visibility really doesn’t emerge at the central goal of political organizing around sexuality until much later.

I don’t want to sound like an apologist for homophobia, but I do think that the homophobia within the Communist Party was not exceptional. It was the norm. The people whom I am interested in were pushing against that, both within and outside those kind of organizational structures and trying to build a better world.

AF: You dedicated the book to Avram Finkelstein, who also conducted the virtual interview with you at the Harvard Book Store book launch on June 16. Who is he?

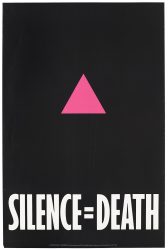

Lecklider: Avram Finkelstein is an activist and artist who became very influential in ACT UP and the Silence=Death collective and HIV activism in the ’80s. In 1986, Avram and five other folks in New York decided they had to respond to the AIDS crisis through art. So they decided to design a poster that they would pass all over New York City. That poster was the Silence=Death poster with the inverted pink triangle that had been used in the Holocaust. That poster has since become iconic, but at the time the idea of drawing on the history of fascism in order to produce a radical graphic to respond to HIV/AIDS was just a profoundly inspired thing to do.

Avram is one of the most beautiful humans I’ve ever met. I ended up curating a show of his contemporary work in 2013, and in the process of doing that we had endless conversations about leftist organizing, queerness, and all of the attendant stuff that we’ve been talking about in this interview. It profoundly moved me and touched me, and it made him into a real, valued friend. So I dedicated the book to him because I wanted to honor what he had given me through his activist work, his artistic practice, and his friendship.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins—Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson—in Salem, MA.