Film Review: This Year’s Tribeca Film Festival Documentaries — From Leonardo da Vinci to Rick James

By David D’Arcy

The Tribeca Film Festival wrapped last week — here’s a selection of the most promising documentaries on view.

Usually falling between South by Southwest and the Cannes Film Festival, the Tribeca Film Festival screens few major premieres — In the Heights was an exception — but worthwhile films find their way in, and the best of those tend to be documentaries.

I say this having covered the festival for the last 15 years.

Here’s my take on some of the docs premiering at Tribeca 2021 — these films may well reappear soon.

Factory worker inspecting the head of a sex doll during assembly in Zhonghan City, Guangdong Province, China, as seen in Ascension. Photo: courtesy of Mouth Numbing Spicy Crab LLC.

Ascension, directed by Jessica Kingdon, won Tribeca’s top doc prize, and it was well deserved. The documentary is made up of observations of the supply chains that operate in the Chinese economy, ranging from products (food, plastic bottles, and mannequins) to the manners of servants catering to the new ultra-wealthy. When goods have to move, people move, mostly to serve someone else’s profit or interests. From what we see, Chinese society is in perpetual motion, and not necessarily for everyone’s benefit.

The title refers, among other things, to China’s economic rise and to the few who are benefiting from that process. The rising tide isn’t coming close to lifting all boats. When workers are recruited, they’re promised lodging — which means an increase in the number of people crammed into a room. It’s musical chairs, at the workers’ expense.

At one point, we see workers sorting thousands of pieces of steamed duck in a hazy industrial kitchen. The temperature appears to be kept just low enough to keep the people alive. In another scene, women workers, drowsy from fatigue, are painting features on department-store mannequins that look more Western than Asian. Kingdon has a sardonic eye for spotting Sisyphean labor, accenting its painful humor as well as its hardship. Contemporary China gives her plenty of painful labor to watch.

Relying more on images than on dialogue, Ascension is in the company of J.P. Sniadecki’s marathon train ride in The Iron Ministry (2014) and Cao Fei’s portrait of a small village surrounded and choked by high-rises in San Yuan Li (2003) — all vivid testimony to what China has become and what it has left behind.

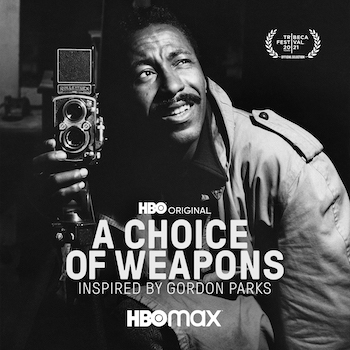

What America left behind in order to become what it is could be an apt description of the photography of Gordon Parks (1912-2006), who is celebrated in A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks, directed by John Maggio. There are echoes of a hardscrabble life, redolent of novels by Dickens and Balzac, in Parks’s bumpy rise from Midwestern poverty in segregated Fort Scott, Kansas. This was a rare triumph for a Black man those days. Parks returned to his birthplace — with his camera — and created a roman à clef that he adapted into a film.

What America left behind in order to become what it is could be an apt description of the photography of Gordon Parks (1912-2006), who is celebrated in A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks, directed by John Maggio. There are echoes of a hardscrabble life, redolent of novels by Dickens and Balzac, in Parks’s bumpy rise from Midwestern poverty in segregated Fort Scott, Kansas. This was a rare triumph for a Black man those days. Parks returned to his birthplace — with his camera — and created a roman à clef that he adapted into a film.

The dutiful expositional style of this doc often feels like PBS (where it might end up), but it gives viewers a rich sense of the breadth of Parks’s gifts in photography, writing, music, and film. Along with a chance to see some indelible images.

There is “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,” the classic 1942 portrait of Ella Watson, a cleaner at the Farm Security Administration, known as an essential worker before that term became a condescending word of praise for those who had to leave home to work during the COVID pandemic. Parks’s restrained yet caustic response to Grant Wood’s 1930 “American Gothic” is a reminder that almost every aspect of life was segregated back then. It often took Black photographers to seek out the dignity in otherwise-invisible Black characters.

Only Parks could have put together the 1948 photo essay for LIFE magazine that looked at a Harlem gangster. There is another particularly revealing image, the group shot of some 50 LIFE photographers, one of whom was Black. That’s one more than most magazines had in those days.

Besides taking pictures, Park wrote (and adapted for the screen) a fictional autobiography. He wrote music, and directed the classic Shaft (along with its sequel), the closest thing to a bona fide Hollywood movie among the Blaxploitation films. Parks’s résumé of accomplishment is so long that this doc can feel like a list. Of course, you can always look up the man’s credits. The photographs show you his heart.

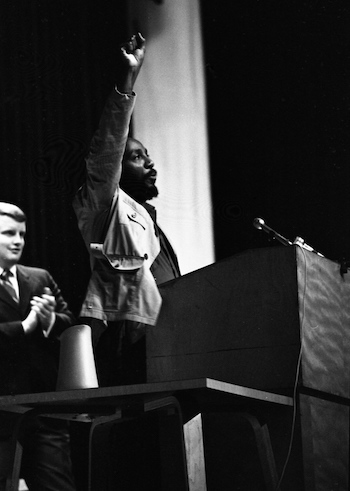

Dick Gregory (1932-2017), the subject of another celebratory bio-doc at Tribeca, shocked white people while he entertained them. Here’s one of his jokes: “I walked into this restaurant and this white waitress came up to me and said: ‘We don’t serve colored people in here.’ ‘That’s all right,’ I said. ‘I don’t eat ’em, bring me a whole fried chicken.’”

In the early ’60s, Gregory was making $5000 a week, a serious amount at that time. His comedy albums were hits.

But Gregory was torn in another direction, as we learn in Andre Gaines’s The One and Only Dick Gregory, coming to Showtime on July 4. He was also active in Civil Rights protests, which led to his being jailed and beaten. As a result, his income plummeted. Still, the pointedly sardonic jokes kept coming: “Everywhere I go folks say: ‘Some of my best friends are colored!’ Now you know and I know there ain’t that many of us to go around.” The archival clips of Gregory on stage (mostly audio) will make you laugh, but he also stressed that “humor can no more find the solution to race problems than it can cure cancer.”

Dick Gregory in Tallahassee in 1969. Photo: Wikiwand.

Gregory, like a Gandhi with a scorching wit, fasted in protest against racial injustices. A runner recruited in college (who never graduated), he also ran as part of a movement to promote health and exercise. Activism didn’t pay the bills as well as comedy did, but he never stopped fighting, quite publicly, for change. Comedians, especially today’s Black comics, watch him with reverence. Beware of success, he warned them: “They gave me the key to the city. And then changed all the locks.”

Bitchin’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James isn’t the same kind of tribute to an empowering subject. With that title, how could it be?

The doc is the story of a guy from Buffalo — not even Cleveland — who created a style and a groove for an audience that was eager for it. For those of you who are not James-ians, the film details the roundabout way the singer achieved success and then destroyed himself.

James came of age just as the Vietnam War gripped his generation. There wasn’t much employment opportunity in Rust Belt Buffalo, so James Ambrose Johnson Jr. enlisted in the US Navy to avoid being drafted into the army. He didn’t last long, deserting to Canada, where he survived in Toronto’s music scene and played in bands with Neil Young and Ronny Hawkins. Who knew?

Just as James’s group, The Mynah Birds, was signing with Motown, the US caught up with the singer, who ended up in prison after escaping custody at least once.

Relocating to L.A., where he claims to have missed visiting Jay Sebring the night Sharon Tate was murdered, the performer, producer, and addict did his best to make the right connections, dodging competitive bullet after bullet as he built a solo act. “She’s a Super Freak” was one of his many megahits. Ironically, the remix by MC Hammer (whom James resented) made more money for James than the original release. Ultimately, James would serve a sentence in Folsom Prison following a conviction for kidnap and rape.

If Keith Richards has had nine lives, Rick James had at least 90. Director Sacha Jenkins evokes the color, the kitsch, and the tragedy of a talent who was lucky to live until the age of 56.

James feuded with the younger Prince over the lyrics “ooh-ooh.” Prince stole the phase, adding insult to injury by imitating James before the older man came onstage when the two shared a bill. As a producer, James also launched Eddie Murphy’s singing career — such as it was — but the man’s real talent was for going over-the-top. His band members, who saw as much of that excess as anyone, still talk admiringly in the doc of James’s talent.

Popular music was all over Tribeca, even in Bernstein’s Wall, directed by Douglas Tirola, a profile of the conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) that, as the title suggests, focuses on his politics.

Years ago this could have been a difficult, if not downright thankless, salvage job, given Tom Wolfe’s notorious 1970 New York magazine critique “Radical Chic.” His takedown of an earnest Bernstein and his wife hosting, at their Park Avenue apartment, a party that included Black Panthers and New York’s moneyed glitterati was devastatingly savage. And read by everyone.

Fortunately for Bernstein, his musical reputation eclipsed his well-intentioned politics and Bernstein’s Wall aims to celebrate his commitment to social issues. Bernstein was a liberal, a progressive on Civil Rights when privileged voices like his were needed. The musical West Side Story, a Romeo/Juliet romance set in the streets of New York, was a plea for peace among warring gangs. Bernstein supported Israel, but he also called for harmony between Jews and Arabs. We watch him making that point in Jerusalem. He also conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in Berlin when the wall was breached in 1989.

Still, Bernstein’s greatest political contribution was as an educator, who worked for decades to bring classical music to young audiences. That included staging his lesson on the then-new medium of television. Half a century later, his work still leads the way.

There is so much to cover in Bernstein’s life and career that any effort to distill it becomes reduced to just that, a distillation. In this case, the documentary feels like an extended encyclopedia entry. Watch it for a chance to see Bernstein converse in archival sections, including a clip where he explains that the “Radical Chic” party was a fundraiser to pay legal costs for a Black man who had just made bail. I hadn’t seen him address that issue before.

A scene of Marin Alsop conducting in The Conductor.

Bernstein also appears in The Conductor, a feature-length profile of Marin Alsop, the former musical director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra who has led the belated emergence of women as conductors of major symphony orchestras. She now leads the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Alsop, the daughter of musicians in New York, had her eyes set on conducting since the age of nine. The filmmaker, Bernadette Wegenstein, wisely stays out of the way and lets Alsop show us what it took to get to the podium.

In one enticing detour, Alsop, a trained violinist, was part of the ensemble Swing Fever, a period jazz group made up of female classical musicians. Anyone who can get classical string players to swing — and Alsop did it for 20 years — will be ready for greater challenges.

Alsop didn’t have many women mentors, but Bernstein was a major influence. In one segment we see him stop the orchestra and ask for the baton while Alsop is rehearsing. We also see a clip of him conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in a performance of Mahler, shaking some of the rust off of that ensemble. Few guest conductors would dare do that.

For Alsop, just being a woman in front of an orchestra stirred things up. She had her struggles in Baltimore, including dealing with opposition within that organization to hiring her in the first place. See The Conductor for a reminder that women who want to lead orchestras still have a long way to go. One major omission. If Boston pioneer Sarah Caldwell (1924-2006) of the Opera Company of Boston appeared in the film, then I must have blinked. Caldwell broke the gender barrier when she conducted the Metropolitan Opera in 1976. Alsop is walking in her footsteps.

Regarding documentaries on films and filmmakers, Tribeca showed Gregory Monro’s Kubrick on Kubrick, which is based on a series of interviews the media-wary Kubrick gave to Michel Ciment, the editor of the French film journal Positif. Kubrick requested that Ciment provide him with a final proof of the text of those talks so he had the chance to revise what he said.

Hearing Kubrick’s voice will be the draw for his many fans. Listening to him talk about his background in still photography at Look magazine — years that he spent after he was rejected from colleges — will be a revelation for many. So will Malcolm McDowell’s noting that his then-shocking performance of “Singing in the Rain,” while torturing a couple in A Clockwork Orange, was improvised by the actor himself. Kubrick was notorious for reshooting scenes dozens of times — but probably not that one. McDowell says that there were days when Kubrick, notorious for being a control freak, arrived on the set with no idea of how a scene would be filmed.

Monro pays closer attention to the elegantly gauzy historicism of Barry Lyndon and the prophetic predigital sci-fi of 2001 than to Kubrick’s other films — Lolita is left out altogether. Predictably, the man ends up as enigmatic as he wanted to be. Even so, this doc packs in revealing details about his life and career. For those who don’t have a few hundred dollars to buy Ciment’s now out-of-print book, you can hear Kubrick’s filmed reflections on photography and his early films on the site Photogpedia by clicking on the link in the paragraph above.

Robert Simon inspects the Salvator Mundi painting at the National Gallery (2011). Photo: Robert Simon, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

The Lost Leonardo chronicles the drama generated by a painting of Jesus (Salvator Mundi) said to be by Leonardo da Vinci, a picture that sold for the world’s highest recorded art auction price, $450 million. The painting was originally bought by two dealers in New Orleans for $1157 — the $450 million came at Christie’s in New York from buyer Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, the thug monarch who sent a crew with a bone saw to kill and dismember the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

In between those sales, some Americans sold the picture to the Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier by way of Sotheby’s for $83 million, and then Bouvier sold it for $127.5 million to a Russian billionaire. The oligarch cried foul when he learned the price that the dealer had paid for it. That’s business, shrugged Bouvier, who had overcharged him on deals before that.

The picture is expensive, but is it a Leonardo? We hear from experts, and from a restorer, Dianne Modestini, who say it is. We also hear that Modestini’s judgment was influenced by visits from her dead husband, another prominent restorer.

We hear from expert skeptics, and then there are the renegades, such as the critic Jerry Saltz and collector Kenny Schachter, who say that, even if it was once by Leonardo, most of it was painted over by someone else. That charge of overpainting reminds me of the joke about the Canadian actress in Hollywood who had so much plastic surgery there that she’s now mostly American.

But the intrigue is not just about attribution. When the picture was included in a Leonardo retrospective at the Louvre, Mohammed Bin Salman, who had stashed Salvator Mundi on a yacht, insisted that it be displayed in the same gallery as the Mona Lisa. The Louvre demurred, and MBS withheld the painting. In response, the French shredded a catalogue that the Louvre had prepared with the Leonardo attribution.

The fracas is far from over. Salvator Mundi is now thought to be in Saudi Arabia, awaiting its resurrection at al-Ula, a planned cultural site and tourist destination whose price tag is reported to $15 billion. Billed as “the world’s largest living museum, where contemporary art coexists with ancient heritage,” the project will serve as the “human face” of the Saudi regime. Can a Leonardo, real or not, wipe the blood off a barbaric ruler’s hands? It may not matter — as long as tourists journey to Saudi Arabia to see the painting.

Be advised – another Salvator Mundi-inspired doc is coming in the fall.

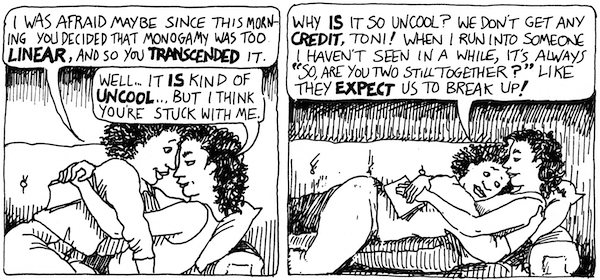

Panel from Alison Bechdel’s comic Dykes to Watch Out For, episode 583, published in 1987, as seen in No Straight Lines. Photo: courtesy of Compadre Media Group.

Odds are that No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics, directed by Vivian Kleiman, won’t be shown publicly in Saudi Arabia. Even at Tribeca it was an outlier, a doc on the emergence of LGBT comics, although they weren’t called that at first. We hear from the artists who made them, existing on the margins of the commercial and underground comic establishments.

Mary Wings, creator of Come Out Comix, was drawn to underground comics in San Francisco. There wasn’t much else, but she cites the “disturbing” work of R. Crumb (subject of a memorable 1995 documentary) as “an example of why feminists would want to make their own.”

It wasn’t just women. There was also Rupert Kinnard, who grew up in Chicago drawing Spiderman and other commercial characters. His real heroes were Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis. “So I thought, ‘why am I drawing white superheroes?’” Kinnard recalled. “The word that keeps coming to mind is bamboozled.” Kinard’s response was a figure called The Brown Bomber, Joe Louis’s nickname during his heyday, an African-American with a cape and a mask, with a lesbian pal named Diva Touché Flambé.

“At college, I had people come to my room and then say, ‘Are you gay?’” he recalled.

We learn that an artist like Howard Cruse (1943-2019) found collaborators and publishers among other artists who thrived in the sex and drug countercultures. “Stuck Rubber” Baby (1995), his story about growing up and coming out in the South, is a comics classic.

Joining these prodigious storytellers is Alison Bechdel, who vaulted to stardom with the strip Dykes to Watch Out For, followed by Fun Home, A Family Tragicomic (2007), a best-selling graphic memoir that was transformed into an award-winning Broadway musical. Her latest, The Secret to Superhuman Strength (2021), is a meditation on aging in the guise of an exercise guide. Bechdel, an art school reject who once wondered whether she could ever support herself drawing comics, may be the doc’s popular draw, but there’s no shortage of fascinating characters here, including the members of a younger crew who have a much stronger support system than the pioneers.

Irreverent, witty, heartbreakingly tender, this was one of the least formulaic docs at Tribeca. No Straight Lines may just put Queer comics in front of more than its mostly self-selected readership. Let’s hope so.

That said, anonymity had its advantages, observes Ivan Velez Jr., one of the younger artists: “You can get away with a lot of stuff. When no one’s paying attention to you, there’s a lot of freedom there.” Everything’s a trade-off.

A scene from JR’s Paper & Glue. Photo: courtesy of the Tribeca Film Festival.

Getting away with things is a specialty of the fast-talking French artist JR, whose signature achievement is placing huge images of children on the Mexican side of the US border wall. As an artist, JR’s strategy is to hide nothing, to create art that is so big, so public, that viewers can’t escape it. He has a paradoxical gift — the larger his subversive images are, the more unthreatening they are felt to be.

JR’s films offer a tour through his various projects, as if they were visual journal entries. Visage Villages (Faces Places) was a 2017 collaboration with the late director Agnès Varda. It was a journey through France (reminiscent of some of Varda’s earlier docs) in which the artists placed wall-sized photographs of people they encountered on local buildings. Think of Christo — then remove the hype and think of someone who alters the landscape discreetly to show who lives there.

JR’s latest doc, Paper & Glue, brings him to a maximum security prison in the California desert and then to housing projects outside Paris that were damaged by recent riots and are now being demolished.

JR’s a gutsy artist, a French guy with an accent and a funny hat, whom we see sitting around a table with prisoners serving sentences of 10 years or more in California’s Tehachapi Prison. These inmates collaborated on a project with the guards: an enormous group portrait photograph was assembled from long strips of paper on the floor of the prison yard. A miracle? The floor mural — best seen from a drone — disappeared (by design) after prisoners walked on it. Paper & Glue was acquired by MSNBC. Check JR’s website for how you can see the film.

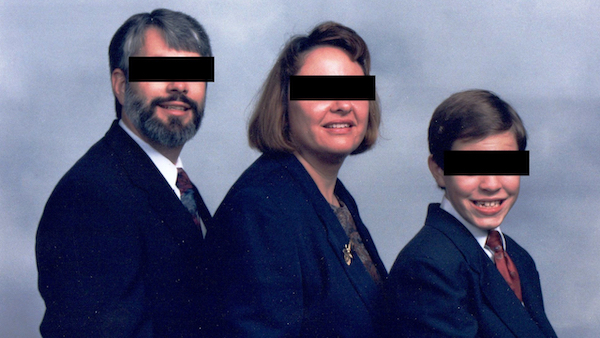

A scene from Enemies of the State. Photo: courtesy of the Tribeca Film Festival.

Lest a Tribeca doc roundup end with a group hug, there’s Enemies of the State, directed by Sonia Kennebeck and executive-produced by Errol Morris. The term Kafkaesque is thrown around casually, certainly among film critics. But, for once, this film about shadowy horrors earns the label.

The predicament of the film’s central character and his family is awful at the jump. A young man, Matthew DeHart, is charged with soliciting children to use them in pornography. A hacker with the activist group Anonymous, DeHart claims he has been interrogated by the FBI — tortured, he says — about a CIA scandal he insists he has uncovered. His parents, both Air Force intelligence veterans (his father is also a Protestant minister), fled with him in disguise to Canada — twice. Matthew pleads guilty to the porn charge, to lessen his sentence, but swears he didn’t do it.

Did he? The film opens with the text of a quote from Oscar Wilde: “The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

The doc offers improbable and conflicting evidence, a lot of it presented in reenactments with the family members themselves. Matthew DeHart is a hacktivist — yet he was given top-secret security clearance from the Air Force before he was discharged, honorably, for depression. He seems innocent and his loving parents defend him. But prosecutors find more and more young accusers. Then there’s the flight to Canada, and his guilty plea.

If the darkest mysteries are those that are buried in enigma, then this is just what Kafka might have ordered. Accusations brought by young boys and other changes permit the FBI to act with impunity. But has this been fabricated by the government, part of a campaign to punish a potential Edward Snowden? Might the US government be using any means necessary to punish someone who might know too much? Get ready for a scripted remake. Enemies of the State’s reenactments already take you part way there. Pick your star. All the project lacks is a love interest, and if there was one, the FBI certainly knows her name. The doc premiered at the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival and opens on July 20.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks, Andre Gaines, Ascension, Bernstein’s Wall, Bitchin’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James, David D'Arcy, Douglas Tirola, Enemies of the State, Gregory Monro, Jessica Kingdon, John Maggio, Jr, Kubrick on Kubrick, Marin-Alsop, No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics, Paper & Glue, Sacha Jenkins, Sonia Kennebeck, The Conductor, The Lost Leonardo, The One and Only Dick Gregory, Tribeca Film Festival, documentaries