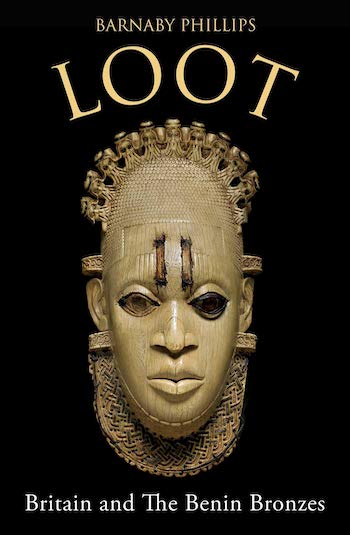

Visual Arts Interview: The Colonial Elephant in the Room — Talking with Barnaby Phillips, author of “Loot: Britain and The Benin Bronzes”

By David D’Arcy

Last week, just a month after the publication of Loot in the US, the Met in New York announced that it was returning two Benin Bronzes to Nigeria.

The Benin Bronzes are as exquisite as the story of their seizure by British forces is gruesome.

The Benin Bronzes are more than 1000 metal sculptures, plaques, ivory carvings, and ceramics from the Kingdom of Benin in what is now southeastern Nigeria. Some date to before 1550, and some have been compared to ancient Greek sculpture and to the work of the Italian Renaissance master Benvenuto Cellini.

They were plundered by British troops in a siege of Benin City in February 1897. Weeks before, an earlier British expedition seeking to loosen trade restrictions set by the oba (leader of the Edo people) violated a ban on foreigners during a religious feast. The detachment was attacked and seven were killed. A “Punitive Expedition” of British troops mobilized from around Africa killed thousands, burned the city, and emptied the oba’s palace of ivory and anything else that could be carried off. Queen Victoria, who received some of these objects herself, congratulated her troops on the operation’s success.

The attack was photographed and journalists covered it approvingly. There was plenty of evidence, but this crime against humanity was anything but a crime in England.

Plunder was part of war then. The British soldiers and officers stole valuable objects fair and square, as the saying goes, upheld by current law. Times have changed: now there’s a rallying cry — from Germany, England, New York, Washington, Boston, and points beyond — to return these looted pieces to Nigeria. The call is part of a broader push for the repatriation of colonial plunder to its lands of origin.

In Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes (Oneworld Publications), Barnaby Phillips, a former BBC correspondent posted around Africa, reconstructs the brutal British attack on Benin City in February of 1897. His book is rigorous, essential, and unsparing in its detail. No one who reads it is likely to see those objects the same way again on visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Phillips stresses that it was never a fair fight in Benin City, even before the attack. The British were hungry to take such resources as rubber and palm oil that factories used as a lubricant. When the British attacked in force, newly manufactured Maxim guns were put to the test, shredding structures and the Africans who defended them. (Maxim guns would later kill plenty of white men in World War I.)

The blood on the pillaged objects was cited when they were put up for sale back home. Dealers and museum curators, who saw Africa as a place without culture or history, were reluctant to acknowledge that Africans themselves made the ivory carvings and sculptures cast in metal. Phillips writes that some “experts” speculated that the sculptures and carvings were made by Portuguese artists, because Portuguese figures were sometimes depicted on them. Some thought the bronzes were the work of itinerant Indians or Arabs.

Museums and collectors scrambled to buy the works. German museums with state funds were major buyers. Dealers found a huge market in America, where collectors often donated them to museums.

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston holds 32 Benin objects. Five in its permanent collection came as a relatively recent gift from Robert Lehman of the Lehman banking family, with a bequest of 25 more to come. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has 160 objects from Benin City.

Phillips traces a patchwork of provenances, taking a rare look at the post-military lives of the 1897 plunderers. He also chronicles the early steps taken by Nigerians to get the Benin Bronzes back. The British Museum (and other museums) had no patience for moral arguments then, Phillips observes, so colonial officials seeking to preserve Benin’s heritage used cash to buy works, effectively ransoming back stolen goods.

But Nigerian security was often lax regarding where those objects were kept. Many were looted a second time, passing again through the art market into private collections and then into museums.

One of those double-looted works was a 16th-century brass head in a Nigerian collection, bought back in the ’50s and removed from Nigeria’s National Museum in 1973 by General Yakubu Gowon, the country’s president, who gave it to the Queen of England. The head is on display at Windsor Castle, Phillips notes.

It wasn’t the first “official” theft from the country’s National Museum. A Benin carved tusk at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston was a gift to JFK from Prime Minster Abubakar Tafawa Balewa in 1961, a year after Nigerian independence.

Another work, a Queen Idia ivory mask, considered one of the finest of all Benin objects, was held by Britain’s regional consul after the Benin attack. In 1958, an official trying to preserve Edo heritage failed to raise enough money — about $30,000 — to buy it back from a noted anthropologist’s widow, who then sold it to Nelson Rockefeller. Rockefeller rejected a request to donate the mask to Nigeria, and gave it to an institution that he founded, the New York Museum for Primitive Art, which closed in 1976. The mask is now in the Met’s collection.

A Benin Bronze head that the University of Aberdeen announced last month it would return unconditionally to Nigeria. Photo: University of Aberdeen.

Today, however, the issue seems at a tipping point. In 2017 France promised to return African objects from its museum collections and released a damning report a year later on its own colonial pillaging. (The Republic of Benin, a former French colony east of Nigeria, was called Dahomey until 1975.) German museums have pledged the return of their Benin Bronzes.

Skeptics (some of them Nigerian) point to existing museums in Africa and warn there’s still nowhere safe to store or exhibit those works in Nigeria.

Now the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye, designer of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington DC, is planning an Edo Museum for West African Art (EMWAA), with 300 works loaned by foreign institutions. The projected five-year plan will place the building in Benin City — if enough money can be raised. (France’s project to return objects to its former colonies is also a five-year plan.) Adjaye’s first funded step is a $4 million archaeological excavation of the Benin City walls, where the surviving moat is now an open sewer.

Adjaye, a star if this movement for restitution and remembrance ever had one, told the New York Times last year that his museum would “deal with the real elephant in the room, which is the impact of colonialism on the cultures of Africa.”

“You need the objects because the objects provide the provenance and the physicality that start to connect you,” he explained.

News of that planned museum comes as calls to exhibit African American artists in US museums have also focused on African art in those institutions. And exploring provenance (history of ownership) often involves exhuming a bloody colonial past. So far, that aspect of the past is more likely to come from books like Loot than from museum exhibition catalogues.

Author Barnaby Phillips

If that history is being exhumed by journalists like Phillips — and, more polemically, by the archaeologist Dan Hicks in The Brutish Museum: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution — it’s also being introduced to new generations though a popular film like Black Panther (2018). A now-famous scene set in “The Museum of Great Britain” has gotten more than its 15 minutes of fame. Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), son of an African father and an American mother, visits the museum and asks a curator where the sculptures on view come from. He corrects her condescending answer and then shatters a display case and grabs an ancient weapon.

There’s nothing like a Hollywood movie to billboard a message. Phillips reminds us that the plunder of the Benin Bronzes has deep roots in Nigeria’s popular culture. The film The Mask (1979) was directed by Eddie Ugbomah, who also stars as a spy tasked with — what else? — stealing (liberating) plundered objects from a museum. The 2014 no-budget Nollywood drama Invasion 1897 revisited the sack of Benin City and made its UK premiere at no less than the British Museum, which seemed not to fear its story.

Last week, just a month after the publication of Loot in the US, the Met announced that it was returning two Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. Based on reporting in the New York Times, the two brass plaques seem to have been looted in 1897, acquired by the British Museum, then sold back to Nigeria by the British Museum, and sold by a dealer who obtained them illegally after they had been in the National Museum in Lagos — twice-looted objects. They were donated by a collector in 1991. A spokesman said the museum will not be handing back its Queen Idia ivory mask, providing no further explanation.

As Phillips explains, despite a greater willingness to return Benin Bronzes in some museums, restitution of colonial objects remains a process of fits and starts.

In Providence, the Rhode Island School of Design will return the one Benin Bronze in its museum to Nigeria. An MFA Boston press person said the museum is in contact with Nigerians in Africa and in Boston and is “in active conversations internally about next steps.”

Encouraging news, but a long time coming. Phillips quoted a Nigerian who said small museums had been most responsive to appeals for the return of objects — “those who have the most we hear from the least.”

Warrior Chief (16th–17th century), brass. Photo: courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Arts Fuse: Is Loot being published at a pivotal moment?

Barnaby Phillips: I think the Benin Bronzes have become emblematic of the debate about colonial looted art. That debate has been bubbling away for decades in the West. It never went away as an issue in places like Sub-Saharan Africa.

President Macron of France went to Burkina Faso in 2017 and made that quite surprising speech — saying, effectively, that it was no longer acceptable that the vast majority of Africa’s cultural heritage was in European museums. He commissioned the Sarr-Savoy Report in 2018 and its conclusions were more radical than anyone expected, also putting the spotlight on Germany and Britain as the other colonial powers. And then you have Black Lives Matter, exploding in the United States during the early summer of 2020. In America, the project was primarily concerned with police brutality. In Europe, it often focused on more historical issues, such as dealing with colonialism, in particular the “ethnographic collections” in museums.

The Benin Bronzes have become the focus of that for two reasons. Partly because there are so many of them and they are so fabulous that the best of them are among Africa’s greatest cultural achievements. And then, they were taken relatively recently, even within the parameters of the colonial period. 1897 is not that long ago. Also, the way in which they were taken was especially egregious. The thief was very well documented, by the British side, both in writing and in photographs.

It’s still an open question whether the restitution of Benin Bronzes, or large parts of the Benin Bronzes collections in the West, which now seems more than likely, will lead to a widespread restitution of other colonial looted objects.

AF: So, are the concrete or logistical issues, if we can call them that, lagging behind what seems like a moral shift?

Phillips: We are in new territory, because we have specific institutions saying they will return specific objects. We have the University of Aberdeen saying that it will return its Benin Bronze head, unconditionally. There’s also the Horniman Museum in London. The University of Cambridge wants to return a cockerel now. We have the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which has 150 Benin Bronzes that were taken in 1897. We have the German museums speaking collectively, promising that restitution will begin in 2022. These are concrete promises, so we are in a new place.

AF: In your prologue to Loot, you describe the sack of Benin City and the seizure of its riches as one of the ugliest episodes in British colonialism. Ugliness in British colonialism is a very competitive category. Why do you say this was one of its worst moments?

Phillips: The British Empire in various manifestations lasted for hundreds of years, and exercised extraordinary power over large parts of the globe. It includes a long list of terrible acts. British involvement in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade is not photographed in the same way, although it’s every bit as horrible.

There are precedents of the British looting cities and civilizations, of course — the Emperor’s Palace in Peking [1860], the Magdala [1868] in Abyssinia — but this was a pretty comprehensive wiping-the-slate-clean of a kingdom’s cultural heritage. Effectively, when they took everything from the oba’s palace, they were ransacking its cathedral, its library, its encyclopedia. Once these objects came to the West, came to Britain, they were inevitably seen as objects of art in an aesthetic way, but their original purposes were religious and spiritual. In some instances they recorded history. Their removal was an act of cultural vandalism, the legacy of which is still with us.

Junior Court Official (16th–17th century), brass (image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

AF: When did the British become aware of the objects’ aesthetic value? When did the British see them as more than objects of plunder?

Phillips: Weeks after the British ships returned, there were stirrings of interest within London’s cultural circles. The first Benin Bronzes went on auction in May of 1897, and the Horniman Museum of South London acquired its first Bronzes in April of 1897. Remember that Benin City only fell on February 18.

But the real moment is in September of 1897, when the British Museum held its exhibition of some 300 Benin Bronzes, which it didn’t own at that point. They were on loan from the Foreign Office. Reviews of that exhibition include words like “remarkable,” “baffled,” “amazed.” How is it that in this sea of barbarism, as it’s been portrayed in the British press, this city of blood and human sacrifice, has produced pieces of such beauty, of such sophistication? Works that some are comparing to the sculpture of ancient Greece, to [Benvenuto] Cellini and the finest works of the Italian Renaissance. There’s great confusion, and people come up with all sorts of theories — that there was some mysterious wandering tribe of Indian or Egyptian craftsmen who must have made them, or that the Portuguese themselves fashioned them. In fact, the presence of the Portuguese figures on the plaques is another cause of confusion, because there they are depicted very accurately, in 15th-century armor, yet we’ve been told that Africa is not only a place of barbarism, but a place with no history. Yet some of these plaques are several hundred years old.

So the aesthetic appreciation comes quickly. Whether that then connects to a moral dilemma — “what have we done to a fellow people?” — that comes much later.

Also, if we’re talking in crude money terms, it also takes time for the serious inflation in prices to filter through. If you’re looking at the soldiers and sailors who sold their collections off in the two or three years after they returned to England, some of them made a tidy sum from what they took from the oba’s palace. But, if you translate it into money today, you’re not talking about the kind of return that was going to transform their lives forever. The serious inflation in the private art market came much later, in the ’60s and the ’70s onwards.

AF: When did these works begin to circulate in the market and in museums beyond England?

Phillips: It happens instantly. In fact, German dealers and curators react with greater alacrity than the British themselves. A lot of that buying goes through a British dealer, William Webster, who corners the market, and that explains the historic size and significance of Germany’s Benin Bronzes collection, which is what we’re talking about today, i.e., the German museums’ decision, collectively, to hand back their Benin Bronzes.

A wider dispersal also begins within Britain instantaneously because so many soldiers and sailors put their pieces up for sale at a series of auctions. There are many more auctions in the ’20s and ’30s, when some of those officers were beginning to die off. In that way, the works are distributed around Europe and the United States, to museums and the private art market.

Relief plaque showing a war chief with two attendants, Royal Bronze-casting Guild, Edo, Benin kingdom, Nigeria. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

AF: Were there any efforts to return those objects to Africa in those years?

Phillips: Already in the ’20s, mostly through the efforts of a man named Kenneth Murray, who was interested in setting up a colonial museum system in Nigeria. Murray was a product of the British Empire, but he was also a Nigerian patriot. He is a hero in the story of the Benin Bronzes. Murry and a British Museum curator, William Fagg, were assiduous in buying up dozens of the finest Benin Bronzes in the auction rooms of London and New York in the ’40s and ’50s and then bringing them back to Nigeria.

That needs to be said. The fact of Nigeria’s collection of Benin Bronzes is often forgotten, because it doesn’t fit conveniently into the arguments today.

When Nigeria was flush with oil money, in the ’70s and early ’80s, it bought back more Benin Bronzes on the private market in London. But Nigeria has experienced many weaknesses and disappointments since independence — a catastrophic civil war in the ’60s, prolonged periods of military rule, many coups, economic decline in the ’80s and ’90s – all of which have meant that Nigeria has not been the diplomatic and moral power that it ought to be.

AF: As pressure to restitute the Benin Bronzes rises, what’s been the effect on the private art market?

Phillips: I feel that the days of high-profile auctions of Benin Bronzes at Sotheby’s and Christie’s are over. What you are going to see more of are private sales. Those sales, in which well-connected dealers know where the private collectors are, whatever you think of them, are perfectly legal. I think they will carry on beneath the radar.

If we look at the broader picture, there are many Benin Bronzes in museums around the world. Those are the lower-hanging fruit that advocates of restitution will focus on first.

AF: How did you feel about the scene in the film Black Panther that took up issues of plunder and restitution in Africa?

Phillips: I felt its genius, since we’re still talking about it now. It captured something that African people had been saying for years — “Oh, come on, your museums are full of this stuff. How do you think you got this stuff?” It’s something that people in Nigeria have been saying about the Benin Bronzes for decades, but they were always voices in the wilderness.

The obas of Benin, who were restored by the British to the throne in 1914, they’ve been talking about the Benin Bronzes since the ’30s. You had campaigners like Bernie Grant in Britain, an Afro-Caribbean member of Parliament, who made the Benin Bronzes a bit of a cause célèbre in the ’90s. But these people could all be comfortably ignored. They didn’t have the power or the platform of a major Hollywood movie seen by millions and millions of people. And that scene made it on social media, where it was viewed again and again on YouTube or Twitter. That reinforcing echo puts the Powers That Be on the spot in a way that wasn’t possible in previous decades.

Contemporary bronze casters in Benin City, 2019. Photo: Barnaby Phillips.

AF: Can you differentiate the efforts by Greece to recover the Parthenon Marbles from current campaigns to restitute the Benin Bronzes?

Phillips: With the Parthenon Marbles, the primary issue is the British Museum. It’s true that the British Museum has the largest single collection of Benin Bronzes (a thousand objects). And, museum curators and art critics might say I’m over my head by saying this, but the British Museum also has the most iconic and, to my eye, the most beautiful works. Still, the Benin Bronzes are in many other splendid collections, from New York to Chicago to Boston to Berlin to Edinburgh to Stuttgart. So they are not only a British Museum problem.

In the past, you might have said that Greece had some significant advantages in this debate, compared to Nigeria. It’s a fellow European country, with very strong cultural ties — millions of British people visit Greece each year on holiday; they certainly don’t go on holiday to Nigeria in those sorts of numbers. And, of course, Athens built a fabulous new Parthenon Museum that blew away any of the residual arguments that the Greeks don’t have anywhere proper to put them. Manifestly, they did, whereas Nigeria’s museums raise many questions that have yet to be answered. Indeed, the current answer to the restitution debate is centered around a new museum in Benin City that does not even exist.

So you would have thought, in that regard, that the Greeks are in a stronger position. But I would go back to Black Lives Matter and its impact, particularly in putting a spotlight on the uncomfortable ways the British establishment and other Western establishments have dealt with these issues when race has become part of the debate. You could argue that the British Museum feels much less comfortable batting away arguments about the Benin Bronzes today than I would think it does about the Parthenon Marbles. That would not have been the case five or 10 years ago.

AF: Where do you see a resolution?

Phillips: We will see smaller museums across the world returning Benin Bronzes, and that’s starting to happen.

For the Benin people, the Edo people, there’s an important principle: these objects belong to them and they were stolen. But as the current oba himself has said, and as his father said before, these objects have been wonderful ambassadors. Nobody envisages a world in which everything goes back, a world in which cultures are limited to the political borders of each nation state. If we can recognize the principle of ownership, if people will finally recognize that these objects were stolen, there is a harmonious future to be had. There will be a wonderful collection of Benin Bronzes in Benin City itself and, if that happens, I really think that it’s the most significant moment in African cultural history since independence. But there will also be wonderful Benin Bronzes that the millions of people who go to the British Museum or the Met every year can still admire at the same time.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Barnaby Phillips, David D'Arcy, Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes