Opera Album Review: An Extremely Effective Operatic “Pasticcio” Made by Vivaldi from His Own Arias and Those by Other Composers

By Ralph P Locke

Vivaldi put this opera together using, in part, arias associated with two famous singers: the “Moorish” (i.e., half-African) Vittorio Tesi and the castrato Farinelli.

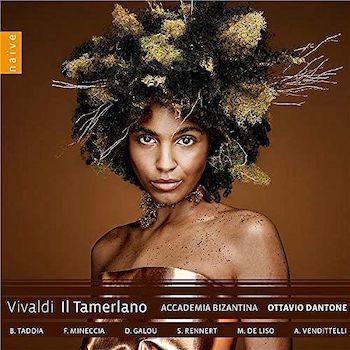

Antonio Vivaldi: Il Tamerlano (Bajazet)

Marina De Liso (Andronico), Arianna Vendittelli (Idaspe), Sophie Rennert (Irene), Delphine Galou (Asteria), Filippo Mineccia (Tamerlano), Bruno Taddia (Bajazet).

Accademia Bizantina, conducted by Ottavio Dantone.

Naïve OP 7080 [3 CDs] 156 min.

To purchase, click here.

Attentive collectors may already own a recording of this opera, a work concocted by Vivaldi for Carnival season in Verona, 1735. A previous recording under the remarkable Fabio Biondi was welcomed by record critics, and some arias (e.g., Irene’s “Sposa, son disprezzata”) have also been recorded separately by such fine singers as Cecilia Bartoli. The Biondi recording retitled the work Bajazet. A download-only recording, by Pinchgut Opera (Australia, less widely distributed) is likewise entitled Bajazet. Either way, the work is, in Ryom’s numbering, RV703.

Attentive collectors may already own a recording of this opera, a work concocted by Vivaldi for Carnival season in Verona, 1735. A previous recording under the remarkable Fabio Biondi was welcomed by record critics, and some arias (e.g., Irene’s “Sposa, son disprezzata”) have also been recorded separately by such fine singers as Cecilia Bartoli. The Biondi recording retitled the work Bajazet. A download-only recording, by Pinchgut Opera (Australia, less widely distributed) is likewise entitled Bajazet. Either way, the work is, in Ryom’s numbering, RV703.

This opera is a “pasticcio”: one in which the composer-in-charge (here Vivaldi) brought together arias from previous operas by himself or someone else and stitched them together as necessary, usually with new arias of his own and new recitatives. The aim, often, was to allow certain scheduled singers to display their special gifts. The practice was long derided by music historians and critics, obsessed by Romantic-era notions of originality and composerly authority. But recent performances have demonstrated that a well-constructed pasticcio can work just as effectively as one entirely composed from scratch.

The composers whose preexisting arias we know are incorporated here include Vivaldi himself (8), Giacomelli and Hasse (3 each: Giacomelli actually composed the “Sposa” aria mentioned above), Riccardo Broschi (2), as well as one by Porpora that ended up being replaced. The surviving score in the Turin library, mainly in Vivaldi’s hand, also contains numerous new arias by Vivaldi (that is, in addition to the eight reused ones by him), but lacks music for five arias that we know were sung at the performances. Suitable numbers from operas of the period (four arias by Vivaldi and one by Giacomelli) have been inserted in this recording, with the texts from Tamerlano underlaid hypothetically.

The libretto by Piovene will be largely familiar to devoted lovers of Baroque opera, because Handel used it for his powerful opera Tamerlano (London, 1719). Handel’s opera has had at least nine recordings, and I devoted a few enthusiastic paragraphs to it in my book Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart.

I’m happy to know Vivaldi’s well-crafted version as well, not least because the current performance is so stylish, energetic, and generally well tuned. It surely helps that the recording was made over a period of ten days (in a convent in Ravenna), rather than being captured on the wing at a stage performance with the singers moving around and perhaps not always focusing primarily on beauty and consistency of tone production.

As Reinhard Strohm’s authoritative booklet-essay details, Vivaldi borrowed numerous arias that were associated with two particularly renowned singers of the day: the super-famous Farinelli and Vittoria Tesi. Farinelli (Carlo Broschi) was the brother of the composer Riccardo Broschi, whom I mentioned earlier; Farinelli was the subject of a lively (if not always historically accurate) film back in 1994.

Vittoria Tesi was a female contralto renowned for her wide range, perfect intonation (at least early in her career), and dramatic acuity. She was sometimes called La Moretta (“The Mooress”) because her father was of African origin. (He was a lackey — that is, a liveried manservant — in the employ of a noted castrato, as scholars have recently demonstrated.) In short, she may be the most notable early opera star of African descent. Further details of her life, and that of her “Moorish” maid Maria, can be read in Michael Lorenz’s richly detailed research account.

The borrowed arias are indeed demanding — many of them very showy, others slow and quite touching. The singers are nearly all up to the task.

Some countertenors take roles that lie a little too low for them, in order to make sure that they can handle the highest notes. Fortunately, that is not often the case here with Filippo Mineccia, who brings real bite and flair to the title role of the Mughal (Turco-Mongol) tyrant Tamerlano, while still maintaining solid tone, note by note — not spitting consonants out at the cost of vowels. He certainly never sounds pressed at the top end of his range. I am delighted to make his acquaintance.

The four female singers are all generally fine, and well differentiated in vocal quality, so one can generally tell who is singing without having to check the libretto or track list. The two sopranos playing male roles (Marina De Liso and Arianna Vendittelli) find just the right “tone,” not overdoing the toughness and thereby spoiling the all-crucial beauty of voice. The two who get to play women (Sophie Rennert and Delphine Galou, listed respectively as mezzo-soprano and contralto) have particularly rich yet tightly focused voices, bringing multiple delights.

Vittoria Tesi-Tramontini. Portrait of unknown origin.

Occasionally one or another of the female singers sings a bit too fast for comfort or overdoes an aria’s emotive content, losing momentary clarity of pitch (e.g., the Idaspe and the Asteria, respectively, on CD2, tracks 3 and 5). This would be perfectly acceptable in a public performance, but could easily have been avoided during the studio sessions.

The only real disappointment is the baritone, Bruno Taddia, in the somewhat secondary role of Bajazet: his voice is quite weak on the low end, he sometimes semi-shouts (e.g., in the excellently crafted quartet, borrowed from Vivaldi’s Farnace, CD2, track 21), and his coloratura is huffy (e.g., CD2, track 15 — a superb aria of frantic despair by Giacomelli).

All of the singers, Taddia included, are wonderfully communicative in the recitatives, and especially in the several instances of recitativo accompagnato: that is, recitative accompanied by fully written-out orchestral figuration rather than just by chord-based improvisations from the basso continuo.

The recording is vol. 65 in the “Vivaldi Edition” (on the Naïve label), a series based on the 450 Vivaldi works that survive in manuscripts in the National University Library of Turin. I greatly enjoyed vol. 61 (Cello Concertos, vol. 3, with Christophe Coin and L’Onda Armonica), and urge lovers of Baroque music to look out for other releases from the series. Among other operas of Vivaldi that have appeared earlier in the series, I might mention Argippo, Catone in Utica, and the aforementioned Farnace.

The 2004 Biondi recording features an all-star cast, including David Daniels, Patrizia Ciofi, Elina Garanca, Vivica Genaux, and Ildebrando d’Arcangelo. (Its original release included a 30-minute bonus DVD.) It can currently be streamed from Naxos Music Library, but no libretto is there to download. The new recording (which is available from some streaming services, though not Naxos) is offered at a sensible price, and its thick booklet includes the libretto in Italian, French, and English. A most welcome arrival!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Antonio Vivaldi, Il Tamerlano, Naïve